Innovation: A Dirty, Sloppy, Time-consuming and Unfair Process

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

Innovation is Great but shouldn’t our innovation strategies be realistic, not Pollyanna-like?

Innovation is very real and very important to long term economic development, not to mention human evolution. The Curmudgeon sincerely believes that. As a short term economic revitalization strategy, however, innovation has become a buzz word–a solution for everything and every community. Want to innovate–Great, just take this course, join my accelerator or mentor group, or try this absolutely surefire new technology or technique and off you go. Everybody can do it. Innovate today and watch the world be transformed tomorrow. The word has been reduced to meaninglessness–and the so-called innovations themselves, ranging from expensive and useless “apps” to changing the color of your iPhone is hawked as the road to prosperity and a new Third Wave world.

OMG–have I become a grumpy old Luddite (look that one up with your innovative google search)?

Sorry, I’m not that smart (those Luddites were right, you know). But I have too much respect for innovation and a heck of a lot of worry about its good-AND BAD consequences– and the unanticipated, and often destructive, paths it frequently takes. Innovation should be respected (as if we respect anything these days) and should not be treated so blithely. So I offer to the reader a relatively short (all right, not all that short) observation focused upon a couple of features pertinent to innovation (rename it “invention” ), drawn from the Great Innovation or the early days of the Industrial Revolution.

Since hindsight is always better than looking into the future, this review goes back to the good old days of yesteryear when innovation was innovation and creativity, well… was dirty, sloppy, time consuming, serendipitous, grossly unfair and not very heroic: the days of the Industrial Revolution (1750-1850). Our comments, drawn from a couple of notable histories of that time period, offer a realistic glimpse into how the knowledge creation and innovation diffusion process actually played out during the Industrial Revolution. Warning! It wasn’t quick and it wasn’t pretty and plenty of things went wrong? Oh and by the way, those great innovators, inventors, well maybe they weren’t all that we make them out to be.

The Curmudgeon is hoping that the reader will contrast that messy, time-consuming, sometimes cruel and grossly unfair process described below with the images of many current blogs, magazine articles, and public policy initiatives that assert innovation is satisfying, wondrous to watch, always pleasant, scrupulously fair process led by brilliant genius entrepreneurs who creatively develop new technologies, products and services chiefly because such entrepreneurs operate in an facilitative, exciting, no-holds barred knowledge-based, knowledge-diffusing world created by governmental and university-led policies implemented by creative economic developers–such initiatives which lead, without doubt or pause, to a new age with plentiful high-paying jobs for all and, of course, prosperity.

YEA Right! Who Are You Kidding?

The Curmudgeon wishes such a world would or even could exist. Instead he believes innovation is facilitated by desperation and greed–neither of which is very pretty. Also innovation isn’t something that creates jobs in an instant. The job creation effects of innovation take a heck of a long time and today nobody ever even hints that some innovation actually kills jobs. In real life innovation kills plenty of jobs and often replaces them with machines. As for entrepreneurism, its not for everybody and when you look at actual innovation through hindsight, it is far from clear what you can teach someone about it. In essence, innovation is real and it is important–but is it really a strategy that economic developers at the sub-state level can expect will turn around their community in relatively short order?

Third Wave? Sure! This Time Really Is Different: Every Blather Needs a Good Tangent and this is it!

The Industrial Revolution! 1750-1850 are you kidding Curmudgeon! We are in a new age, Curmudgeon, a post-industrial age, a third wave age (burp!). What can we possibly learn from the dinosaurs of the 19th century?

The Curmudgeon separates himself from those who think of our present epoch as a “new age”, a “third wave”, a “post-industrial society”. To those who hold such a perspective, the historical past can offer little insight into what lies ahead. For them, we have entered a brave new world. Unfortunately, there is a tendency with these new age proponents to assert that they alone can define this new world and that they alone have the instruction manual, the road map. This new “world is flat”, they assert, and it has evolved to the point there is little to be learned from the past. The winners are those who leave the past and best understand the new opportunities of the new epoch. History is irrelevant–strip it from the STEM curriculum.

To this the Curmudgeon intelligently and coherently, but firmly, replies “Bull-doo-doo”. This Time is Different is the best indicator there is of an innovation “bubble”–a bubble spasming out buzz words and magic bullet solutions for instant prosperity. As we all know, trees, like innovation grow to the skies and never fall (knock down electric lines, catch blight, or burn)–Right? Come on!

Step back for an instant. Give some thought as to what this innovation thing really entails. How many decades does it take before demand and new technology permit successful commercialization? What is the real “stuff” required of entrepreneurs if they are to ultimately succeed–can you really teach how to steal someone else’s widget and get historical credit for an invention you didn’t pioneer? And is innovation so smooth and quick and so easy to achieve–a “plug and play” creativity and knowledge-diffusion process which is guaranteed to produce innovation and enhanced productivity which never kills jobs, occupations, sectors and ruins lives and lifestyles or recreates the social-economic class structure so that future Marx’s have something to write about.

So the Curmudgeon believes our present age, our current society and the global economy is still safely contained within the Industrial Revolution era. How can he believe that when so much has changed? Well, one early industrial revolution invention was the railroad–and now Richard Florida in his Great Reset is talking about High-Speed Rail as the driver of growth in the new age! It seems to the Curmudgeon that the industrial revolution invention, the combustion engine, is now being rejiggered to nat gas and that is called “alternative energy” and is a gazelle cluster. Yea, sure, the industrial revolution is so “24 seconds ago”.

The Industrial Revolution, even through it started hundreds of years ago, is still churning and evolving, and glimpsing into its early features can offer insight into what innovation and knowledge-diffusion really looks like. Back then you could have read this article on reproduction from a lithograph printer; today you digitally download it–and possibly print it out on a laser printer. Kind of takes your breath away, how far we’ve come (sarcasm!)?

The Curmudgeon believes, our present economy is just a phase in an on-going Industrial Revolution. (Paul Bairoch now with IHS Global Insight, writing for the Financial Times, says we are in the seventh period-June 11, 2012). Factories still make semiconductor chips and cell phones and software shops still manufacture apps. Obviously the industrial revolution has evolved from its earliest fascination with water power, textile manufacturing, and locomotives driven on wooden rails–but our economies still revolve around goods made, even if the cutting edge of goods are digital rather than material (Bairoch calls this last period “the new industrial revolution”–a not very imaginative label, the Curmudgeon observes).

To be sure, the current phase of this, rather long in the tooth, Industrial Revolution, is much less factory-based, than information and service-based, and is more focused on communication technologies. But cell phones and Internet to the contrary, our economy is still based upon the science, the scientific method and technology first unleashed by Newton, Bacon and their ilk, and manufacturing, be it advanced or low wage, is still regarded as the critical enabler and beneficiary of technology, creativity and innovation.

We can learn from lessons drawn from the Industrial Revolution And as to any brave new Third Wave world–the Curmudgeon proudly proclaims that his GPS gets him lost every time, but he does know a couple of historians you can read who do possess a firm sense of how the original Industrial Revolution first played out and may broaden your perspective about how amenable innovation and knowledge diffusion is to plug and play programs and strategies.

Diffusing Knowledge From The Past

Stealing from these two insightful historians, listed below, we will return to yesteryear when innovation was king and knowledge was diffused–without the Internet, the iPhone or the incubator.

(1) The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy, Joel Mokyr, Princeton University Press, 2004, (2) The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World, 1776-1914, Gavin Weightman, Grove Press, 2007.

Anyway, the two books are quite different in their approach and content. Most academics would not be likely to link one with the other. Weightman’s book, in fact, is probably considered soft, or popular history (it is pleasurable to read and therefore cannot be considered sufficiently rigorous for academic publication). Mokyr is concerned with basic knowledge, how it was discovered and how it was transformed into applied knowledge during the first two hundred plus years of the Industrial Revolution. The incredibly long and complicated time span between knowledge discovery, successful commercialization which allowed the knowledge to become the engine of economic growth which he retells can today, no doubt, be shortened by that weekend workshop and crowd-sourcing, and really good marketing.

Weightman, on the other hand, is focused on the personalities and life stories of the key innovators and entrepreneurs who seized upon this knowledge and converted it into innovations and technologies — the process we today label commercialization. The stories focused on key inventions and innovations are quite complicated and the key inventions take years before the various pieces are put together. The real life serendipity of real life people (oftentimes very strange, obsessive people) strikes the Curmudgeon as an excellent counter to the one way street to inevitable success we find so prevalent in the literature today.Many of the poor souls who really created and invented died broke and disillusioned. In no discernible way do we see magic bullets, Great Resets, or anything approaching a linear, rational straight line evolution from creativity, to knowledge diffusion, to innovation, to commercialization and onward to jobs and prosperity.These two works offer us a useful reminder of how disjointed, messy and lengthy is the cycle from knowledge discovery to successful commercial application, to actual economic growth. Also, they offer a realistic appreciation of the role “Great Men” play in innovation and commercialization. Finally, Mokyr and Weightman can restore meaning to the world “innovation” which in today’s literature has been warped and woofed into meaninglessness.

Mokyr concentrates on the rather fragile link between basic research and applied research. He tells a tale (without really meaning to, the Curmudgeon thinks) of how inventions (what we today call technology) sput and sputter from basic research to applied research and then ooze into multiple, unintended, eventual commercialisation, very often in totally unrelated fields or sectors. A key issue is that as basic knowledge moves toward its evolution into applied knowledge it can shift to completely different academic disciplines, it can stall for considerable periods of time awaiting the development of new technologies and knowledge (for instance, the railroad steam-boiler engine, being too heavy for the wooden railroad ties, needed to wait twenty years for the Bessemer steel production to evolve. The two quite separate technologies combined as iron and steel replaced the wooden ties and allowed the heavy, but creative and innovative steam boilers to be loaded on the locomotive. Then Weightman tells us the story of how additional delays, and treachery followed as financing and competition for contracts further befouled the successful introduction of the technology.

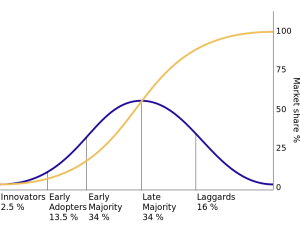

In summary, Mokyr uncovers, in some cases multi century, gaps between the discovery of “useful” knowledge, its commercial application, and its triggering of economic growth and jobs. To explain this almost inevitable gap he observes there is a need for a required intermediate stage. This intermediate stage between discovery, commercialization and subsequent economic growth is necessary because discovered knowledge must be broken down into into bits and pieces, applicable to specific inventions useful to a specific industry sectors, and then linked with other related technologies. Only at this point, assuming sufficient demand exists, can an entrepreneur-commercialization put together the financing, and the marketing, and the cost-minimizing productivity that permits links the product to end-user.

In summary, Mokyr uncovers, in some cases multi century, gaps between the discovery of “useful” knowledge, its commercial application, and its triggering of economic growth and jobs. To explain this almost inevitable gap he observes there is a need for a required intermediate stage. This intermediate stage between discovery, commercialization and subsequent economic growth is necessary because discovered knowledge must be broken down into into bits and pieces, applicable to specific inventions useful to a specific industry sectors, and then linked with other related technologies. Only at this point, assuming sufficient demand exists, can an entrepreneur-commercialization put together the financing, and the marketing, and the cost-minimizing productivity that permits links the product to end-user.

Crucial to the intermediate stage is access (diffusion) to the knowledge and information by anyone who thinks they can use it , often through what today we would call “social networks” and occasionally through venture capitalists who link seemingly unrelated innovations and technologies to a business plan. Successful commercial innovation requires use of multiple inventions and innovations usually drawn from sectors and sources unrelated to the final product. Because of this leap frogging across industry sectors, the need to combine innovations and inventions, and the time gestation necessary to create demand–the prerequisite for the availability of financing, INNOVATION IS UNPREDICTABLE, EVOLUTIONARY, SUBJECT TO FALSE STARTS, AND SPASMS OF PROGRESS, and often FOLLOWED BY INITIAL COMMERCIAL FAILURE.

At its best, innovation does not reliably produce short term profits, jobs, or economic growth. Innovation and entrepreneurship is resistant to rational positive action and planning. Innovation’s cemeteries are filled with inventors who died alone, broke and unknown because the potential of their innovation was successfully commercialized years after their death. Buried alongside these unknown innovators are investors who “picked winners”and who also died penniless and unknown.

Great Men (and Women) With Great Ideas: The Hero Entrepreneur

At this point Weightman takes over. As he describes the path of several “platform technologies” (such as steam engine, combustion engine, the mobile combustion engine (railroad engine), steel, petroleum as an energy source, cars, torpedoes, and plastics) he recounts the lives of the key innovators-entrepreneurs and the various problems and opportunities they encountered. Invariably, a good idea of concept required a working model, financing, simultaneous competition with other ideas and concepts, including copies of his own (often illicitly stolen) and then near insane period we today label commercialization in which the product innovator becomes distinctly weird, obsessive, egocentric and immoral–and usually results in someone other than the innovator making the real money. A reader of today’s literature on innovation and entrepreneurism gets little feel for this very brutal, lengthy, unfair, and oft times immoral process which has so many twists and turns, detours and serendipity that one has to wonder how an professor teaching a course in innovation can possibly prepare his student for what lies ahead. In the world of Weightman in particular, innovation, diffusion of knowledge, and commercialization is a world with:

- a trial and error process extending over a period of time which can be quite lengthy, hidden or what today we call proprietary and certainly not open and shared, as its the stylish motif of our day (of course, everyone shares their code);

- multiple simultaneously competing similar inventions in several different geographic areas, many of which ultimately disappear while still others succeed– resulting in variations of the same innovation across different geographies

- innovations with better science and technology can often fail because they lost the battle for commercial success

- stealing what is, in effect, proprietary information (despite the rights of patent) as a common occurrence, accounting for more diffusion of innovation than orthodox and legal diffusion of ideas

- commercialization required and linkage of both timely financing and market demand

- innovation does not automatically create its own demand–some great ideas just sit around for decades because no one wants its products or others can figure out how to use the innovation to their profit

- innovations often require linkage with seemingly non-related technologies (e.g. railroad steam engine got nowhere until steel manufacturing innovated to allow the replacement of wood rails with steel rails)

- innovation which emerges from the above constrains seem to require an obsessive, almost insane, commitment by the entrepreneur-commercializer, who …

- for one serendipitous reason or another stumbles upon a better support system, discovers an immediate buyer, or through political access was able to achieve a competitive edge (even monopoly) over rivals

. The picture Weightman paints is brutal, unfair, and frankly sad—the better inventor, the best technology, the nicer, more deserving guy does not inevitably win! In fact, he seldom does. The discover of knowledge does not benefit from its commercialization and usually economic growth only arrives when commercialization is timed with market demand for the innovation (hence Resets play little to no role in the final stage of discovery-innovation-commercialization except possibly clearing the deck of decaying technologies and firms).

As to the Great Men/Women theory of innovation (examples such as Jobs, Curie, Einstein and Edison), we start with Mokyr who minimizes their role:

As to the Great Men/Women theory of innovation (examples such as Jobs, Curie, Einstein and Edison), we start with Mokyr who minimizes their role:

“A century ago, historians of technology felt that individual inventors were the main actors that brought about the Industrial Revolution. Such heroic interpretations were discarded in favor of views that emphasized deeper economic and social factors such as institutions, incentives, demand, and factor prices. It seems, however, that the crucial elements were neither brilliant individuals nor the impersonal forces governing the masses, but a small group of at most a few thousand people who formed a creative community based on the exchange of knowledge. Engineers, mechanics, chemists, physicians, and natural philosophers formed circles in which access to knowledge was the primary objective…. these elite networks were indispensable, even if individual members were not. Theories that link education and human capital in technological progress need to stress the importance of these small creative communities jointly with wider phenomena such as literacy rates and universal schooling”.

Weightman, however, describes how these “small creative communities” actually competed, stole from each other, came together, and broke apart in an instant. Separately each small creative community worked hard–or not, fell apart, recombined into yet another “small creative community”, and then were crushed when one successful entrepreneur completely outside these creative communities drove them into bankruptcy. Weightman’s retelling of history lends little support to our current university-led mentoring group, facilitating technology transfer through a collaborative infrastructure” incubator-like environment! The process Weightman describes is more like Zuckerman and the Winklevoss Brothers or the Pirates of Silicon Valley. None of these great men and their firms passed through our economic development creative programs.

Let’s Talk Specifics: Some Examples From Weightman

Much of the current innovation/diffusion of knowledge programs and initiatives, such as accelerators, is built around the notion that conscious intervention, usually by the public sector, can meaningfully and positively alter and shape the patterns of private innovation and technology commercialization. The Curmudgeon will defer any comment on that assumption to a future article. In the meantime, the relevant question is whether we can automatically assume that such public intervention will be beneficial and effective—and that its unanticipated outcomes sufficiently predictable and non-disruptive. Perhaps the best way to answer that question is to summarize one Weightman chapter on the Great Man, Thomas Edison and his invention of the incandescent bulb and establishment of the world’s first public lighting system.

In other chapters, Weightman argued that a good deal of America’s early innovation was stolen outright from Great Britain by American entrepreneurs and inventors, the prime example of which was Carnegie. But in “The Wizard of Menlo Park”, Weightman argues that Edison became acknowledged as the inventor/innovator, not because he discovered the technology and was the first to use it, but because he copied, tinkered with a variety of existing technologies and systems, and through astute public relations and fortuitous British legislation, his technology emerged as victorious.

Weightman alleges that Edison did “not get on with science at all” and by Edison’s own admission Newtonian physics “gave me a distaste for mathematics from which I have never recovered”. (P.328) The secret to Edison’s success (with the exception of the phonograph) was that:

What Edison was good at was thinking up things that needed to be invented and getting financiers to back him while he worked out how things were done or, more often, hired the person who was likely to discover the solution to a particular problem. (p.328)

Edison, it has been claimed “subordinated invention to commerce”–… there was no point in making something that nobody really wanted.” (P.333) Weightman in earlier chapters had already developed the concept “subordinated invention to commerce” in his description of the careers of previous innovators-entrepreneurs such as Watt, Boulton, Wilkinson or Bessemer (all associated with early iron making-coke furnaces).

As such Edison’s early career involved improving already existing technologies in the hope of improved commercial success. That was his business model at Menlo Park (his private research park on a site identified by his Dad) and in tinkering with the telephone technology of his rival Alexander Graham Bell, he tripped upon the technology which allowed him to record conversations and play them back. Edison was thirty years old.

So, he hired young George Bernard Shaw to hawk the wonders of this new technology to financiers and Shaw actually wrote “The Irrational Knot” (1879) promoting Edison (then only 31) as a celebrity inventor. In any case, the outcome of his competition with Bell was to patent the “talking back” technology and it would eventually became the basis for the phonograph (1877). While the technology had considerable promise and got quite a bit of media attention (Edison actually formed the Edison Phonograph Company at this point), the quality of the technology was so poor, demand never materialized and Edison lost interest and abandoned the technology for over ten years. (P.334)

Depressed with this failure, Edison traveled to Wyoming (July 1878) to witness an eclipse of the sun. On the trip he met and made a new friend George Barker, a professor from UPenn. Barker during the trip awakened in Edison an interest “in various applications of electricity, including its use in lighting”. (P.335) Barker when they returned arranged for Edison to visit a Connecticut firm that had an electrical generator technology and were “experimenting with carbon-arc lighting systems and looking at the possibility of sending electrical currents over long distances”. (P.335) Edison visited the firm (along with a reporter from the New York Sun whom he brought along). The technology was a real whiz bang and it got Edison charged up and he quickly developed (and publicized) a vision of the world lit up by HIS lighting system which provided electricity to all homes using the basic business model for the then existing gas network. With a fairly decent publicity campaign, he attracted sufficient capital and venture investors to proceed. Remember, reader, the technology is not his and the vision, is, well, a vision only.

At this point, it may be worth mentioning that European cities already had operating electric light systems. In particular, the “Jablochkoff Candles”, marketed by La Societe General Electrique (General Electric), founded in 1853 and which using generators to power arc lamps built lighthouses as early as 1857 ; by 1877 the Gare du Nord and the Louvre, and assorted households throughout Paris were already lit. In 1878, the Societe Generale expanded their franchise to London and using existing viaducts lit up portions of the city, including the Billingsgate Fish Market. Thirty thousand fans watched a night soccer match that year (1878). By 1881 English firms were entering into contract with municipalities for electric-arc public lighting systems. One such contract to a firm named Calder & Barrett, involved a new technology by an inventor, Joseph Swan, the incandescent lamp bulb which would be used to light up public areas.

Swan and a partner, had worked on incandescent lights for many years and eventually had developed the technology, involving a celluloid filament and a clear glass bulb, once another technology, the vacuum pump, had been devised. Easy to manufacture, these bulbs were being used by 1879 (Swan’s poor partner accidentally blew himself up with nitro-glycerine that year). The lamps were not without some defects, but two brothers, the Siemens brothers from Germany, bought the technology from Swan in 1881. Nevertheless, by 1881 several English cities and Paris had functioning public electric light systems and an incandescent bulb.

Back to Edison. For use in individual homes, Edison (1879) needed a new version of the incandescent light bulb (whose technology we now know had been lying around for over thirty years a la Swan and Societe Generale).

… working on the same principles (as Swan and Societe Generale), the frenetic experimenters of Menlo Park had produced not only their version of the incandescent lamp but something approaching an entire electrical system designed to fulfill Edison’s dream of lighting up cities from a central generating station. (P.339)

The (1881) Paris Exhibition (devoted to electrical equipment) was the ideal stage on which Edison could outshine his European rivals. (Siemens was there with his electric tram, Bell with his telephone, and Trouve with his electric car (they still haven’t got that technology nailed down yet))

Assembling both a technology team and a publicity team, Edison headed to France and launched what amounted to a modern style public relations and publicity campaign. The Exhibition formally had a public testing between four competing incandescent bulb technologies (including Swan’s and another American Hiram Maxim (ever hear of him before?- a bigamist, he had sold his technology to Edison in 1881 and went on to invent the Maxim machine gun and made a fortune in the arms trade of WWI). The technologies were virtually identical, and no one technology was declared the winner, but through a clever use of (charges of bribery were to follow) French journalists Edison got top billing and while trying to woo both French and English, he set up his first electricity station in NYC (1882) claiming it was the first “public lighting system in the world using incandescent bulbs”. (P.340)

English competition ended in 1882 when English “gas and water” socialists led by Joseph Chamberlain passed a law taking over the English gas and light firms, making them public authorities and outlawing private systems. Germany’s AEG, copying (some say stealing) Edison’s model and technology, spread the public electric light system throughout Germany. AEG bought some Edison patents and the rest as we say is history. AEG is still a powerhouse household and energy systems innovator today.

Some Parting Shots at Innovation

The real world of innovation and entrepreneurism, if it resembles that described by Weightman and Mokyr, is not what we see in our economic development literature. If Edison’s story is anywhere near accurate, it is hard to see how he would have submerged himself in some professor’s class, learning how to be an entrepreneur and how to develop an innovation. As opposed to starting his own accelerator (Menlo Park), he never would have entered somebody else’s. He was not known for sharing his ideas–his preference was that others share their ideas with him. But all said and done, innovation requires submerging science to commerce, the community good to individual profit. that is so dirty and capitalistic. Today, we are told, innovation and entrepreneurs transform cities and regions; they do, but over considerable periods of time, for their own profit and glory, and they create new sets of winners and losers. As a byproduct entrepreneurs and innovators line their own pockets or aggrandize their egos, deserved or not, to capture the glory and wealth.

None of this, for instance, is Florida’s “creative class”, or even his “Super-Creative Core”, and it certainly is not about young, hip, and “the totally awesome” flowing to “cool cities” for a great lifestyle. This innovation as enjoyment and coolness must be an evolution peculiar to the Third Wave because it certainly doesn’t seem to fit into the Second Wave. It’s not clear how Mokyr or Weightman’s reportage of history would fit into a “Creativity Index”, a region’s underlying creative capabilities”, or it’s “openness to different kinds of people and ideas”.

In both Weightman and Mokyr there is little sense that urbanism itself plays any distinctive innovation generating role. Indeed, the earliest stages of the industrial innovation occurred in the absence of modern urban areas– in areas of low density. It was the Industrial Revolution that created and populated our current “modern” cities not the reverse. And one thing that appears certain from reading either of these works, is that innovation is not confined to a geographic area. Innovations arise in several regions almost simultaneously, and being first to generate an idea-innovation by no means guarantees that the region will develop the final commercial end-use product/service. Innovations did not confine themselves to any geography in 1800 and it most likely, it won’t today. The thrust of innovation is iterative, constantly adding onto other innovations, and combining with innovations in unrelated disciplines and technologies which facilitate production, consumer demand, or commercial scale-up. The research center that produces innovation is but the first step in a long, unpredictable, chaotic and nasty journey. It is not a short term fix for jobs next year!

Indeed many key innovations and technologies, critical to American (and almost any other nation) industrial growth were simply stolen from successful commercialization across the “great pond, the Atlantic Ocean in England, France and Germany-they did not result from a cluster-like agglomeration or from urban density. They resulted from larceny, and reverse engineering and all the good things we accuse the Chinese of.

Simple density or aggregation was not required in our Industrial Revolution and members of the early industrial innovation. Weightman describes one critical technological innovation (the Stephenson locomotive engine which powered the first modern railroad line in 1825) occurred because a bankrupted inventor, seeking asylum from creditors in the wilderness (i.e. low density) of Central America, stumbled upon the adventurer-son of another inventor in an unrelated technology working in a Central American minefield. This is called serendipity and is taught at most major universities under the rubric “strategic planning”.

Finally, in regards to the innovation icons. There was nothing “cool” about their lifestyle; they were relaxed in an obsessive and anal compulsive sort of way and the innovators were as likely to be psychologically dysfunctional than constructive team members. Their family lives anything were anything but familial, and many were essentially loners who used people rarely and reluctantly, only to discard them when no longer deemed useful. What a fun group this was (is). No doubt they shared their insights and knowledge readily with others and collaborated with fellow innovators in a team environment (sarcasm!)!

Read biographies (or attend movies) on Gates, Jobs, or Page and get a sense of how warm hearted collaboration really characterizes our innovation process. and finally compare Weightman’s treatment of Edison with Florida’s worshipful respect of Edison, and one senses a fundamental disconnect of the latter with the street reality of a knowledge-based, innovation economy. One may say the same regarding the current economic development literature and Federal policies and programs which seek to advance innovation. To believe one can rationalize greed, desperation and serendipity is, the Curmudgeon believes, an overstepping of the arrogance threshold.

The current innovation policy push presents a much too simplistic and positive tone to what is a disruptive, frequently nasty and dark, always greedy and narcissistic individual-driven process. What’s more innovation is always a two-edged sword, unleashing creative destruction which is great if you are a gazelle–not so great otherwise. Innovation may make great national policy, but for a local economic development strategy it really makes swell pollyannish rhetoric.

Comments

I agree with the viewpoints offered by the author of this essay. The economic issues facing the United States today will not be solved by the extensive use of “groupthink”, i.e. the work of any one federal government committee, program, “stimulus package”, or by a one-size-fits-all approach to creativity. All those initiatives are contrary to the individual, madcap, and free innovative spirit that made (and still make) this country great.

In a capitalistic economic system, it is the individual that thinks of the next great idea and then subsequently creates jobs to support that idea. It is the individual that must sit down, work hard, and create the next Microsoft, GE, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Facebook, Apple, etc.! The process is, as the author says, not “cool”: it is frenetic, long, and torturous. Many inventions are developed out of the life experiences of their inventors, thereby creating an emotional investment in the invention’s success. That emotional investment is what drives the inventor (sometimes to the point of madness)to see their idea come to fruition or a sputtering halt.

The government (I am sorry to say) cannot do any of that work for us! All government does is tax these smart, talented individuals into a position where they cannot reasonably be expected to invest any capital into new ideas or to hire any new staff. They then take that money and ironically use it to fund the aforementioned ineffective innovation and job creation programs!

I believe that the only way out of our economic problems is to not to rely on the government to do it for us. We must be like the inventors of the late 1800s-early 1900s. Bold, wiley, willing to get our hands dirty, and unwilling to let the government provide a thing for us. (Other than an armed forces and national security, that is!)

Comment by Stefanie on July 10, 2012 at 5:42 pm

I have read so many content regarding the blogger lovers but this article is in fact a pleasant paragraph, keep it up.

Comment by here on February 3, 2013 at 8:17 pm

The comments are closed.