Business Climate and the Second War Between the States

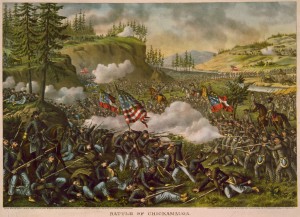

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

In October 2011 the Curmudgeon wrote a review entitled “Business Climate in the New Normal”. This is both a MAJOR rewrite and a SIGNIFICANT update.

Business Climate and the Second War Between the States

(Or Do We Mean the Political Parties)

Everyone in economic development has heard about state business climate and the ratings and rankings that are published by virtually every Think Tank, Trade Association and Policy Institute in the nation. You know, the one’s that are headlined on Yahoo News “East Lugwrench is Number One in the Nation for UGGs found on the highway”. This headline is usually followed by an ad in Area Development by the Economic Development Department of East Lugwrench urging all to relocate to the UGGs capital of the nation. “You “shoe’d come to East Lugwrench” “We’re not UGGly any more”!

The use of business climate rankings as an economic development strategy is pervasive throughout the profession and its use is certainly not in decline. Now that, for example, we have tip-toed into 2013, there will be raft of these rankings telling us who did what in 2012. Several are already published. The Curmudgeon is writing this review because he believes you should make a New Year’s resolution not to enter into this silly and politicized minefield.

Having set the stage, the reader probably expects that the Curmudgeon will review and critique several of the more prestigious business climate rankings such as State Business Tax Climate Index, the CNBC Annual Ranking, Milkin Institute , Quality of Environment Versus Quality of Life, Area Development’s States for Doing Business Survey, the State New Economy Index, or the US Chamber of Commerce’s Enterprising States. But it’s not quite that simple. The Curmudgeon has other ideas.

Specifically, the Curmudgeon has the following formal objectives for this review. First, he wants to make sure the reader understands that most of this literature reflects the polarized debate between blue and red and serves little purpose than to expose the stupidity of the other side. Secondly, the Curmudgeon suggests caveats regarding the methodologies that are frequently employed in the rankings and climate studies. Thirdly, the corporate decision to accept or reject an incentive and the goals or quid pro quo the city/state wants in return are both very badly understood. The result is a pathetic sense of how business climate investment decisions are made and what consequences follow. Finally, the Curmudgeon will review three studies of business climate rankings. The first, by George Bittlingmayer, Liesl Eathington, Arthur Hall, and Peter Orazem, “Business Climate Indexes: Which Work, Which Don’t, and What Can They Say About the Kansas Economy”, prepared for Kansas Inc; the second, Gauging Metropolitan “High-Tech” and “I-Tech” Activity”, Karen Chapple, Ann Markusen, Greg Schrock, Daisaku Yamamoto and Pingkang Y, Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 18 No.1 p. 10-29; Joseph Cortright & Heike Meyer, Increasingly Rank: The Use and Misuse of Rankings in Economic Development” Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 18, No 1, February 2004, p. 34-39 & Response by Paul D. Gottlieb, p. 40-43, and the final study, “Business Climate Rankings and the California Economy, Jed Kolko, David Neumark and Marisol Cuellar Mejia from the Public Policy Institute of California. Each of these studies will question a vital aspect of business climate rankings or analysis.

Isn’t this truly more than you ever wanted to know about economic development business climates?

The Preamble (Pure Curmudgeon Blather on the nature of business climates)

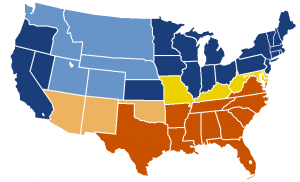

Most rankings are little more than bullets fired at an enemy–and like all bullets, they should be dodged. When you follow an index the reader becomes a willing reenactor in the second war between the states, and cannon fodder in the reds versus the blues polarization of America. Perhaps, if no one read this stuff, it might eventually go away.

In fact, we are reluctant to touch any state or city business climate studies–although we will. With very few exceptions, most should never be read. Period! Most rankings are little more than bullets fired at an enemy–and like all bullets, they should be dodged. Most indexes and rankings will decide for you what is valued in a business climate and toss out all the rest. You are playing their game in their ball park when you follow an index. And in the process the reader becomes cannon fodder in the polarization of America. If nobody read this stuff, it might eventually go away.

But the problem, as the reader well knows, is that there are only six of us in the entire nation, if not planet, who agree with the Curmudgeon (and four are dead, drunk or institutionalized). In the real world, the media, academia/think tanks, blogosphere, and politicians constantly seize upon these “index-things” and publicize them to all heck, rave on and on, yelling and screaming at the immoral and or just plain stupid folk and wasted communities that are on the bottom of the rankings heap. Business climate “studies-rankings” and the subsequent reaction to them by economic developers, media, and the average Joe and Josephine bring little credit, or job creation, to anyone.

A major reason for all this diatribe is that few understand the nature and characteristics associated with state, regional and community business climates.

- Business climates don’t come from nowhere. They actually grow on trees: historical and political culture trees. States and communities grow their own business climate tree and that tree grows and continues over time because it is nourished by a political culture which changes slowly and fails to prune its limbs as it ages. Each state and community reflects at least fifty to nearly one hundred years of economic development tradition, distinctive types of EDOs, reliance on time-honored subset of economic development tools and strategies, a constant geographic location, and if we are to give credence to the Big Sort, attracts and retains residents who think, and probably vote, alike over time. Climates, like cultures, don’t turn on a dime and they don’t change character overnight–or from year to year.

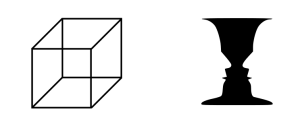

- The business climate of a state or community is the cumulative aggregation of policy decisions across departments, policy areas, and time periods, which are based on a sense or belief by the decision-makers of what force is ultimately judged to the best generator of jobs and economic prosperity. The three most common beliefs upon which cumulative policy outcomes are built are (1) low taxes, cheap and skilled labor, inexpensive cost of living, and less regulation are best or (2) public goods such as infrastructure, health care, environment, transportation and education are essential prerequisites, (3) and innovation, regional high-growth sectors-clusters, creativity, knowledge-based entrepreneurs and new business formation are best. While states and communities will always pick one from (1), one from (2), and one from (3) overall, overtime one or another of these approaches will be preferred and will characterize the business climate.

- There is no way to prove definitively for all time which of these (or any other) approaches is correct or the best. There exists no consensus, excepting of course, the very latest public opinion poll, which is clear as to which climate is the most effective in generating jobs. And so the preferred choice among climates ultimately rests upon belief, a secular-semi-religious act of faith that one type of climate is the economic salvation of the community-which, since we are dealing with the aggregated sum of policy outcomes, becomes inter-meshed with politics, partisanship, elections and political ideology.

- Accordingly business climate will reflect the dominant belief system expressed through politics, elections, and institutional/bureaucratic inertia all of which transform business climate into a battleground between conflicting belief systems, political ideologies, and political parties. Legitimation, of the position of each rival climate-type will be forged from studies, analyses, and methodologies which will receive acceptance and agreement from its true believers and be semi-automatically rejected by its rivals who will cite their own studies, rankings, analysis.

- Each of these studies, rankings, methodologies, and analyses will select out of the total business climate only those aspects, variables, policies which they value (and leave aside unconsidered all other elements of the business climate). They will then find/construct imperfect indicators with which to measure these variables and the end-points or policy effects that are supposed to be achieved. The observed impact of the salient variables will then be correlated or linked with the output of the entire state or community business climate (including all that which was not considered) and the efficacy of the salient variables-climate will be highlighted and victory proclaimed.

In this perspective the sad reality is that business climate is irretrievably, deeply enmeshed in polarized ideologies with conflicting values, a preference for red or blue, and contrasting perspectives toward business. The literature of business climate is produced by authors and institutions that are anything but neutral from the get go. There is little to no objectivity and no matter how sophisticated the methodology or the statistics, their numbers do not necessarily mean what the rankings suggest.

In this perspective the sad reality is that business climate is irretrievably, deeply enmeshed in polarized ideologies with conflicting values, a preference for red or blue, and contrasting perspectives toward business. The literature of business climate is produced by authors and institutions that are anything but neutral from the get go. There is little to no objectivity and no matter how sophisticated the methodology or the statistics, their numbers do not necessarily mean what the rankings suggest.

Enough of the Preamble

For the Curmudgeon two take aways from the above paragraphs are (1) favorable business climates should be positively well received by firms and companies and as such should be understood/employed by economic developers and ; but (2) what passes for almost all business climate indexes, rankings, commentaries, reviews and critiques should be ignored, but aren’t and, therefore, we need some really basic “101” review on how to approach and deal with this silliness.

In the discredited opinion of the Curmudgeon, the following “101” observations should be considered. The business climate “literature” needs to be judged by, evaluated by, tempered by the following concerns

- Business climate is just that: climate for business. It should be viewed from the firm’s perspective–if it works and the cost is acceptable, do it. If you don’t know what you want from business or can’t measure it, don’t do it. The idea is for business to use the incentive. If you don’t like business, then regulate/tax the hell out of them–they’ll go away eventually and you’ll have the climate all to yourself. If you love business like little Reese’s Pieces, then send them a contribution at Christmas. Business climate incentives are a business decision from both sides–both sides gets something out of it or it shouldn’t be done.

- Climate is like weather. Extreme temperatures, either hot or cold, are not good; it’s the temperate, moderate climates that most of us like to live. Being the hottest temperature in the US will only attract a certain kind of entrant–all the rest will head for the hills where it is cooler. But temperatures are only one factor; ice storms, hurricanes, fires, droughts, tornadoes, 85″ snow storms, and never-ending high humidity also enter the picture. Indexes based on only one or two themes (taxes, innovation, right to work, high technology, green etc) are simplistic because it is impossible to for most firms (and methodologists) to separate out one theme from any aggregate statistic such as job creation or GNP or business formation. Climate is the whole shebang; not just one element.

- Which brings us to numbers and methodology! Cost-benefit studies and correlation analysis are in reality used as ideological weapons; as the definitions, indicators and assumptions reflect the conclusions desired–and if you think you are dealing with a “neutral analyst or scholar” doubly hold onto your wallet because there is no such thing. Methodology is like sculpture. One starts out with a solid block and then “shapes” it into the form desired. Numbers are, what the numbers are; but the meaning and interpretation of the number is a work of art, not science. Indicators selected as criterion by which one measures the phenomena seldom are adequate to the task at hand. There is no magic associated with an r squared, or a 95% significance level. These are measures of association, not legal proof.

- Business is like climate; it is a composite word. There are different kinds/sectors of business; manufacturing, high-tech, bio, logistics, service and retail and any incentive/regulation will have differential impacts. Also, many firms operate in more than one NAICs code at the same time–a single firm can be a basket of sectors and to pull out only one product/service line and define the firm as this or that is just wrong. Finally, Businesses do different things and behave in different ways: they create/destroy jobs, improve earnings, innovate, pay taxes, increase wages, pollute, contribute to the community, and buy goods and services from other community business. To select one indicator to measure all this is futile and if you allow a researcher to do this, shame on you.

The Loosey-Goosey Nature of a Business Climate Transaction

State business climate is important–it is not just a weapon in the ideological polarization of America. How can we better understand how business climate plays a role in the decision of a firm to stay, leave or enter a state?

The reader is probably desirous of striking back against this blatheresque diatribe by screaming “it does always have to be like this”. “States do have different business climates and some are more successful than others’. “State business climate is important–it is not just a weapon in the ideological polarization of America”! Actually, the Curmudgeon does agree and, wakes up each morning, sharing in the reader’s outrage and frustration. Business climate does exist and it can be a very important aspect and strategy of economic development. How can we better understand how business climate plays a role in the decision of a firm to stay, leave or enter a state?

The goal of a favorable business climate is to encourage firms and companies to do “something” (locate and pay taxes, create jobs, innovate, pay higher wages, etc) which is regarded as desirable–in the particular state, not somewhere else. Stupidly, no doubt, the Curmudgeon believes that incentives or carrots, if regarded well by their eligible recipients, will induce a positive response or action from the firm, though admittedly the response or action may not necessarily be the desired behavior sought by the state (not create jobs originally promised, reduce jobs or relocate, reduce shifts, not meet union demands, seek additional tax reductions).

Conversely, regulation (the stick) will usually produce less of what is regulated although, admittedly, regulation can provide stability and predictability to a firm. It appears from this really simple expression of the dynamics unleashed by a business climate that already there are no simple answers. A favorable business climate can elicit, from the state’s perspective, some unwanted firm behaviors and regulation can be interpreted by different firms differently and accordingly produce different outcomes as well. This is not a good start. Then there is the law of unintended consequences and things can even get worse. State business climate is a transaction, as we said earlier, but business climate is like all transactions: it involves risk.

This is why claw backs, penalties for failing to live up to the transaction’s quid pro quo are frequently employed in incentive programs; but it is very difficult to levy a claw back on a business climate-induced activity by a firm; business climate is not a contract and the quid pro quo is largely unarticulated by either party to the transaction. Indeed, just the opposite. Each party may have different, if not conflicting ideas, what the quid pro quo involves. Business climate is therefore very open-ended. Essentially the hope, and no mistake, it is at best an informed hope, is that the net, net of all firm actions and behaviors at any point in time is positive for the state.

Again, as mentioned above, business climate studies and rankings never, never study or rank the total state environment any how the other factors in the state environment affect the firm and its decision. Nor does the business climate study assess the total set of actions and behaviors of the firm relevant to the state as it evaluates how well the firm lives up to the implied quid pro quo. Once more for emphasis: Business climate studies select out only a sub-set, sometimes only one element, of the firm’s state-related environment (taxes, right to work, innovation, specific favorable climate for a highly valued sector) and these state factors are then related to a desired goal or set of firm behaviors, such as job creation etc which is regarded as the quid for the favorable climate quo.

The idea behind all this is that the state has chosen a specific firm behavior desired from the firm after it locates in the state and that this is clearly transmitted to the firm. The assumptions underlying the business climate assessment also assume that the firm has looked at the state business climate, assessed those aspects that were favorable, and balanced the favorable benefits with the costs of the quid pro quo, and then made its decision to locate in the state. In essence, the business climate study has built into its equation that the quid pro quo is clear, understandable and acceptable to all parties in the business climate transaction. Failure on the part of either party to satisfy the quid pro quo is an abuse or an unwillingness to live up to the other’s side of the bargain.If you accept our loosey-goosey sense of a business climate translation, no contract exists, neither side has a clear sense of what the other side expects from the transaction and no clear-cut sense of which output by the firm is the sine qua non of the state (or the indicator selected by the business climate study (and we must remember that firms have many outputs; firms can reduce the number of jobs and increase the wages-benefits-working conditions of existing employees for instance). Given that firms survive by making profits, not creating jobs (which is the usual measure of many business climate studies), it is quite likely that something is going to go wrong or that the study may be ignoring costs incurred by the state through firm behavior.

In essence, given the loosey-goosey impreciseness of the business climate transaction, the failure to appreciate the universe of outcomes produced by the firm which may result in a net, net benefit to the state, the conflict in goals (profit versus jobs) inherent to both parties, and the complete lack of clarity and understanding by each party of what quid pro quo involves–how can this transaction be measured at all.

The Three Reviews

he first review is written by George Bittlingmayer, Liesl Eathington, Arthur Hall, and Peter Orazem, “Business Climate Indexes: Which Work, Which Don’t, and What Can They Say About the Kansas Economy”, prepared for Kansas Inc (Kansas Inc. is a state entity whose mission is to strategically build a strong and diversified economy that promotes new and existing industries), June 2005.

Kansas Inc confirms the Curmudgeon’s perception that “Numerous organizations rank states on the basis of their business climates. These rankings are widely discussed in the media and are cited by elected officials, business associations, and consultants…. However, the rankings often conflict and there is little guidance as to which rankings are valid or invalid” (P.1).

They further support our perception that “the number and variety of indexes has increased since 1999” (P.3). The growth in the number of indexes is the consequence of (1) “advances in information technology that have lowered production costs” (they are cheap to produce), and (2) and an explosion in the use of such indexes to affect public opinion and policy change (P.4). The latter observations offers support to our position that most of these indexes and rankings are political-ideological in nature and purpose.

To assess validity (i.e. whether the indexes actually account for past growth, and/or predict future economic growth) the Kansas study tests eleven well-known business climate indexes (over a thirty-two year period-1970-2002). Kansas Inc. asks the rather elementary question as to which indexes are positively correlated with various different measures of economic growth. Accordingly, they draw four measures of growth from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ Regional Economic Accounts: county-level wage bill, population and employment changes, and number of non farm proprietors (business formation) as their dependent variables. Interestingly, to explain the relative economic performance between states, they study the neighboring counties (107 state borders) on the borders of each state where the impact of differing business climates should be most apparent and impactful.

“None of the business climate indexes can explain a large proportion of the variation in economic growth across counties. The best performing business climate indexes explained at most 5% of the total variation…, suggesting that most of the variation … is due to factors NOT CAPTURED by state-level business climate measures. This would suggest that business climate is relatively unimportant in driving relative growth among the states”

“None of the business climate indexes examined by Kansas Inc can explain a large proportion of the variation in economic growth across counties. The best performing business climate indexes explained at most 5% of the total variation…, suggesting that most of the variation … is due to factors NOT CAPTURED by state-level business climate measures. This would suggest that business climate is relatively unimportant in driving relative growth among the states” (P.10); Or it might suggest that the business climate indexes do not capture the totality of the entire business climate.

Only two (Fantus, Grant Thorton) of the eleven indexes can consistently explain a small amount of the variation in one dependent variable (relative wage bill) over the thirty years (P.11); and three others (Clemson-Pacific, Small Business Survival, and Tax Foundation) explained smaller amounts of the variation in other dependent variables. Four of these five indexes mentioned in points 2 & 3 above placed between 70-100% of their weighting on tax and regulatory burden and size of government (P.11). “Therefore, it would seem that relative tax competitiveness seems to matter at the borders” and indexes that “place relatively high weight on tax policies had the most consistent positive effects on relative growth” (P.13), albeit accounting for a fairly small percentage of the variation among states; [underlining=Curmudgeon]. Some indexes (Fraser Institute and Corporation for Enterprise Development) not only cannot explain growth at all, but are negatively correlated with all four measures of economic growth (P.12). Indexes that weigh industrial policies “have no ability to explain relative growth…”(P.13)

Kansas Inc discovers the obvious: that different indexes measure different things, implying that different variables create economic growth. In essence, the great number and variety of indexes measure different variables indicating some confusion and “flexibility” as to which core elements of business climate (and logically public policy) are critical to achieving a successful, competitive and growth-prone business climate. Business climate indexes do not measure or compare the same variables and each presupposes its often unarticulated “theory” as to what causes economic growth. It should be no surprise that Kansas Inc concludes “most of the indexes are not highly correlated and clearly measure different things” … and “41 of 66 cross-correlations are negative” P.7. In short, there is no real consensus as to what actually prompts job creation and business climate prosperity. If so, picking an index of business climate is almost a matter of self-interest or individual theoretical/ideological choice. Despite the math and sophisticated methodologies, there is only humbug in business climate.

This plethora of indexes which compare apples to nails provides support for Kansas Inc’s observation that indexes have multiplied in part as yet another mechanism by policy advocates and ideologues urge their desired policy changes be implemented throughout the fifty states. Indexes most certainly possess a political and ideological dimension, but the only indexes which can claim some small measure of credibility, according to Kansas Inc, are those which focus on tax and regulation.

This plethora of indexes which compare apples to nails provides support for Kansas Inc’s observation that indexes have multiplied in part as yet another mechanism by policy advocates and ideologues urge their desired policy changes be implemented throughout the fifty states. Indexes most certainly possess a political and ideological dimension, but the only indexes which can claim some small measure of credibility, according to Kansas Inc, are those which focus on tax and regulation.

Another interesting finding revealed by Kansas Inc’s analysis is that whichever the index, and however the index index defines business climate, the business climate itself does not materially change over time–that business climate is amazingly durable (“business climate is a very persistent phenomenon” (P.17) and does not exhibit meaningful variation as a consequence of changes in policy during the time period (P.6).

Do actual policy changes result in subsequent changes in business climate? According to Kansas Inc. they don’t! Changes in policy do not seem to result in changes in how a state ranks in economic growth or interestingly on rankings by the same index over time. Winners and losers in an index may move up and down a few notches each year, but the same winners and losers emerge–over decades– despite any changes in policy undertaken in each state.

Winners and losers in an index may move up and down a few notches each year, but the same winners and losers emerge–over decades– despite any changes in policy undertaken in each state.

This durability of business climate over considerable periods of time seems counter intuitive in that some of them must, on occasion, change their policies to addresses their weaknesses and emphasize their strengths–but they don’t! On closer thought, the durability makes sense if one recognizes that business climate of a particular state is composed of many, many elements, from policies regarding taxes, regulation to educational systems, and that incremental changes in any one policy are not likely to result in dramatic changes in the state’s overall business climate or, claims to the contrary, economic growth. This durability may even suggest that policies are not the most important element in a state’s business climate–maybe, just maybe, the most important element in a business climate is the image desired audiences have of the business climate. Maybe, the reality just doesn’t matter? What a depressing thought that is!

If taxes and regulation are so important, why are some high tax/regulated states economically prosperous?

Our second review article “Business Climate Rankings and the California Economy, written by Jed Kolko, David Neumark and Marisol Cuellar Mejia from the Public Policy Institute of California (mission is “to inform and improve public policy in California through independent objective nonpartisan research), April 2011, asks a rather interesting question. Why is California’s economic performance better than its business climate rankings suggest it should be? And if the rankings do not reflect California’s economic performance, what does this imply for the usefulness of these rankings? (P.2).

First, the Curmudgeon did some fast fact-checking (using BEA) of California’s performance relative to other states (and nations) and California, probably as expected, was uninterruptedly the nation’s largest GNP throughout the last ten years. In fact, it is the seventh largest GNP in the world (assuming the USA is removed). In the period 2005-2009 the USA grew GNP by 11.7% and California, 16.1%. Whatever the business climate of California may be, the Public Policy Institute’s position is that California grew at rates exceeding that of the overall USA is supportable. Whether this is a relevant comparison, should, for instance California be evaluated by comparing it to specific states with presumably different business climates, is more open to question.

Texas, with a smaller base than California grew 26.7% during this period (interestingly the absolute growth in dollar terms was almost the same) and New York, 10.4% (below USA average and nearly one-third less than California). Whether or not California is a super-growth machine (which the Public Policy Institute goes out of its way NOT to claim) is certainly not open to question, but, in the war of bad business climates California does quite well. California is always growing above the national average.

The California Policy Institute (CPI) generally sees business climate indexes as falling into one of two basic “types”: (1) “those that measure the business climate in terms of productivity, including measures of the quality of life and human capital, and (2) those that emphasize taxes, regulation, and other costs of doing business”

The Public Policy Institute generally sees business climate indexes as falling into one of two basic “types”: (1) “those that measure the business climate in terms of productivity, including measures of the quality of life and human capital, and (2) those that emphasize taxes, regulation, and other costs of doing business” (P.2). In so doing, the authors acknowledge the apple and oranges aspect of this bi-modal distribution of business climate indexes. As to which set of measures actually constitutes the “real” core state business climate, CPI takes no position. They too do not sense a consensus exists as to what is the ultimate best generator of jobs and prosperity.

They very subtlely suggest (at least to the Curmudgeon) an underlying tension between these index-clusters. The two index-clusters seemingly divide the fifty states into two covertly competing armies (dare we say the Red and the Blue). Yet, despite a logic which may be evident to the Curmudgeon only, this apparent zero-sum relationship can in real life, at some points in time and under certain conditions, permit both armies, under conditions favorable to each, to be victorious over the other in certain time periods.

The authors observe that the California business climate does much better in the former (productivity), and miserably in the latter (taxes). They also point out that California has grown wages and output at rates exceeding the national average.

They then systematically review eleven prominent indexes (including the Progressive Policy Institute, the Information, Technology & Innovation Foundation (Kauffman Foundation), the Corporation for Enterprise Development, the Tax Foundation, the Milken Institute, the Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council, the Pacific Research Institute, and the Cato Institute).

Their initial observation was that every state in the Union did well in one or another of these indexes-clusters. And every state did poorly on one or another index-cluster. In other words, each index-cluster defines economic growth differently, and employs different indicator-measures to capture that version of economic growth. The reality is, however, that each index winds up being able to prove their versions are correct because each has, in effect, stacked the deck. Choose an index, adopt their definition of economic growth, and away you go. The reader is just along for the ride.

With so many ways to describe the business climate, the RIGHT QUESTION is not only whether the business climate matters for economic growth, but also which, if any, of the business climate indexes help predict economic growth, and which policies captured by the business climate indexes are the most important predictors of economic growth

This observation obviously leads to a second question:which index-cluster is the superior predictor of economic growth! Which particular index in the index-cluster really does produce “true” economic growth

“With so many ways to describe the business climate, the RIGHT QUESTION is not only whether the business climate matters for economic growth, but also which, if any, of the business climate indexes help predict economic growth, and which policies captured by the business climate indexes are the most important predictors of economic growth“. (P.8)

The answer to this question is not easy or simple. Is there a consensual indicator of economic growth which uses the same database and the identical indicators to measure that growth used by the eleven separate indexes? No! So the Institute aggregate all the individual measures associated with each of the eleven separate indexes and groups them (factor analysis) into fourteen distinct variables. They then rank the states on these fourteen variables, and using correlation analysis, they further construct thirty or so “sub-indexes”. CPI then correlate the entire barrage of groups and sub-indexes against commonly used measures of state economic growth drawn from the National Establishment Time Series data, Dunn-Bradstreet and the Quarterly Census of Employment & Wages.

The results of these correlations further confirm their initial finding that there are in fact two macro-industry clusters emerge (actually three): (1) those indexes which emphasize productivity/quality of life/human capital (5 indexes) and (2) a cluster which emphasizes “taxes and costs” (5 indexes); and (3) a third which does not fit either classification (1 troublemaker). [The Curmudgeon urges those who are methodologically inclined to view their Technical Index which is quite exhaustive and descriptive of their methodology and which can offer a more precise description of their methodology]

When the thirty sub-indexes are individually correlated with these measures of economic growth, “three stand out in having a consistent, statistically significant relationship with our economic growth measures…. These three sub-indexes-the SBTC corporate tax index, the EFINA size of government index, and the EFI welfare-spending index–all fall within the taxes and costs cluster….

None of the sub indexes within the productivity/quality of life cluster has a consistent {and statistically} significant relationship with economic growth….” None of the sub indexes within the productivity/quality of life cluster exhibited a consistent {and statistically} significant relationship with economic growth…”.

Positively stated, if there is any policy/industry cluster associated with the business climate literature that has a limited, but persistent, statistical impact on economic growth, it is taxes and spending! This conclusion is congruent with Kansas Inc’s research. Also, CPI’s research supports Kansas Inc’s finding that business climate index rankings usually do not vary over time. The observable, but unseen and unrecognized, reality of any business climate index, no matter how constructed or which side of the industry-cluster fence it is on, is that business climate change little, if at all, over decades. If so, the durability of business climates makes regression analysis only marginally useful in assessing and understanding individual business climates. Yet, regression analysis is a common tool of many indexes.

Correlating the thirty sub indexes with cluster-groups, CPI discovered that within each ranking or index “states often rank consistently well or poorly on indexes WITHIN each of the two clusters” (P.12) and sub indexes and rankings within a cluster do not really change over time. The rankings of the various indexes also do not change meaningfully from year to year. If you do well on an index this year, expect to continue to do so in future years. Other than marketing impact, what is the real difference in being first on a ranking in one year and third in another. Has the state slipped, someone else caught up, or has the arithmetic created a meaningless distinction? State business climates do not shift if one successfully alters a single policy area–the Curmudgeon, going back to an earlier observation, observes state business climates are just too big and multi-variated to offer any hope that any one policy change can produce a meaningfully different business climate. The possible exception, suggested by both Kansas Inc and California Public Policy Institute, might be tax reduction.

How Important is Public Policy Change in Materially Affecting a State/Region’s Business Climate?

At the outset, the Curmudgeon does not wish to imply, or enter the fray as to whether any of these single policy/related theme proposals that are usually advocated by each index or ranking can generate jobs or some limited economic growth. That very quickly becomes a war of competing definitions and methodologies. The real issue is whether positive changes in any one public policy area (enhancing innovation or attracting tech firms for instance) can overpower everything else that is going on in the other policy areas of the state business climate. A second, and related point, is how long does that policy change have to be in effect before one can really see a measurable change in the employment or economic growth of the state (or region). If positive change requires a decade before it is evident some other economic developer (governor) is going to take credit–not you.

There are other ways to approach the question than “if” or how quickly a single policy can produce sufficient momentum to alter a state’s overall business climate. CPI pursues another path. They believe a key issue lies in what one includes in the definition of a business climate. CPI then posits that what is usually left out of conventional definitions of business climate may be more important, than the public policies usually at the core of these indexes. They suggest that non-public policy factors shape the state business climate, and arguably, are more important in affecting the rate of economic growth of that state.

Kolko et al note that California does not do well with either of the two index-clusters. Admitting in their own, more tasteful, way that California stinks in the tax and costs cluster, and is mediocre in the quality of life cluster. Yet, despite recent setbacks in the Great Recession period, California’s economic growth has been consistently above the national average for decades. In essence, the authors logically question whether business climate, as measured by most existing business climate indexes, really captures the driving forces behind state economic growth. What gives?

Kolko et al state that business climate indexes “overlook the possibility that California’s economic performance may depend on factors beyond the reach of policy, such as weather and geography” (P.13) which can offset other favorable and negative policies. This kind of talk is heresy to political-economic junkies. CPI identifies other non-policy drivers of economic growth such as: disproportionately concentrated sectors (clusters if you must) which prosper or slump depending on the time period; natural features such as climate, and proximity to waterways (i.e. current transportation modalities); also listed are the shift in the national economy to a service sector economy; the location of natural resources; population density (i.e. rural versus urban); and a natural attractiveness for human interaction (i.e. attractive to tourists). Kolko et al also remind their readers that these frequently overlooked factors VARY WITHIN THE STATE as well as between states (P.14).

“Taking the evidence on business climate indexes at face value, California’s economic growth is held back because of policies that lead to a poor ranking on these indexes. But California is also fortunate to have natural advantages with regard to other factors that boost economic performance. The two forces are offsetting, so despite its relatively poor business climate, California’s economic growth comes in near or above the national average (P.18).

The Curmudgeon would expand still further the definition of business climate to include: governmental structure and processes, demographic configuration, political culture, natural resources, settlement and immigration patterns, geographic location and population distribution among city, suburb, small town and rural environments. This is a hodge-podge to be sure, but their listing force the reader to move beyond the narrow, policy-limited world in which most indexes and rankings exist.

Business location studies have long lists of salient variables such as: right to work and prevailing wage issues. But ease of construction (i.e. environmental regulations), cost of living, access to alternative logistical modes, synergy with other corporate facilities and the current corporate business plan, and consumer demand. All of these factors (and more) exist alongside any policy change advocated in an index or ranking–but are simply forgotten, unmentioned, and simply ignored by policy advocates. If correct, that business climate is amazingly simplified in most climate rankings and studies, the potential for most public policy changes to materially affect the overall state business climate are grossly exaggerated.

A Statistical Interlude: The California Institute article includes a very pleasant surprise in the form of an Appendix B which briefly summarizes and critiques several of the best articles written concerning business climate indexes in the last thirty years. The reader is therefore referred to this Appendix with the understanding that a bit of statistical background will be very useful in getting the most from the appendix. From the Curmudgeon’s perspective, this appendix reviews the earliest indexes, first constructed during the 1980’s (indexes which centered chiefly on taxes). These early indexes garnered considerable media attention and academic assessment of these early indexes acknowledged some limited explanatory impact of taxes and costs on employment, and that employment was seemingly affected by the ideologically controversial “right to work” policy.

More importantly, the Appendix outlines a series of statistical and methodological concerns regarding indexes and analysis of indexes. A methodologically non-sophisticated economic developer should be cognizant that there is no accepted methodology with which to conduct and evaluate business climate indexes, their claims, and even their underlying methodology. Issues such as “reverse causality”, time lags between dependent and independent variables, and unclear and conceptually imperfect independent and dependent variables are, in themselves, serious deficiencies commonly associated with indexes and rankings.These methodological failings materially affect the credibility of business climate claims and projections. Repeating the concerns of Fisher (2005), Kolko et al. observe that:

often business climate indexes … fail to measure accurately what they claim to; that including economic outcome measures in indexes that purport to predict economic outcomes is circular; and that index construction often involves weighting components arbitrarily rather than based on their actual predictive power (P.23).

To add insult to injury, Kolko et al critique our previously-cited Kansas Inc. After describing Kansas Inc’s methodology, which employs only a single year of each business climate index for each of four ten (or twelve) year time periods, Kolko et al wonder, if in fact, Kansas Inc may have tripped over a “reverse causality” problem. (P.24). The strength of business climate rankings and studies often is felt to lie in their math and methodology–CPI suggest, and the Curmudgeon agrees (who cares?) that in real life these studies and rankings are saturated with methodological-statistical and logic fallacies which mask their principal purpose: to wage ideological war.

Specialized Rankings: The Difficulties in Ranking High-Tech Industries

Many economic developers know enough to stay away from the deeply ideological rankings based on variables like taxes and right to work, but they tend to be more accepting of rankings that assess high technology, entrepreneurial environments and innovation. These strategies can arguably be viewed as “blue state” approaches to economic development, but in all fairness their use has permeated into red states and all sorts of economic development agencies in all sorts of climates currently embrace, at least rhetorically, these approaches. So rankings and indexes in this specialized policy area abound. Unfortunately, these specialized climate rankings are not immune to either the issues we have raised thus far or their own serious definitional and methodological problems related to how they define technology, innovation, and entrepreneurism. Definitions matter! So …

Accordingly, we will briefly discuss a ranking system, proposed by Karen Chapple, Ann Markusen, Greg Schrock, Daisaku Yamamoto, and Pingkang Yu, “Gauging Metropolitan ‘High-Tech’ and ‘I-Tech’ Activity, Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 18, No.1, February, 2004 and two commentaries by Vijay K. Mathur and Joseph Cortright published in the same issue as Chapple et al’s article. [Underlining=Curmudgeon] [By the way, the rankings themselves are dated (1990’s) and the point of this review is not the specific findings and rankings, but rather the methodology, values and data involved]

Chapple et al develop a ranking of high-tech in American metropolitan areas. Their ranking is “defines” high-tech in terms of the occupations associated with high-tech industries. “We identify as high-tech all three digit SIC manufacturing and service-producing industries with 9% of their national workforce in science, engineering, and computer professional jobs …” (p.10-11) … we then tally all jobs in these industries for MSA/PMSA that added the largest number of aggregate jobs in the 1990’s” (p.11).

Chapple et al than compare their rankings with four other ranking systems (Progressive Policy Institute, AEA/NASDAQ: Cybercities, Brookings Institution [performed by Cortright & Mayer–author of the commentary], and Milken’s America’s High-Tech Economy). Each of these four alternative climate studies define high-tech in different ways:

In essence, four business climate studies, all sharing a similar view of the world, each valuing high-tech industry highly as an economic development objective, arrive at disparate conclusions and recommendations–and, needless to say, rank different metro areas differently.

-

-

- PPI: 50 largest Metro Areas, Index based on multiple measures across five categories (such as knowledge jobs, globalization, digital economy, economic dynamism and technological innovation capacity.

- Cybercities: 60 Metropolitan Areas, defined high-tech as selected manufacturing SIC, plus communications services, and software services [not including bio tech, pharmaceuticals, and aerospace], used 1998 county business patterns data.

- Brookings [and Cortright]: 14 mid to large sized Metropolitan areas [Chapple argues is allegedly biased to Coasts and Sunbelt and excluded the largest metropolitan areas], defined high-tech with [narrowly} specified NAICS codes which grossly corresponds with the Cybercities definitions, and used 1997 Economic Census data.

- Milken Institute: 315 Metropolitan Areas, using a modified shift/share methodology of “degree of concentration of high-tech output” in the metro’s economy [which Chapple alleges gives greater weight to newer, nonindustrial metro areas], but Milken’s definition of high-tech is the broadest of the four, including defense, motion pictures, engineering. Industries were selected on above average R&D and “technology using occupations”. Unlike all other studies which used employment as measurement indicator, Milken used “output” or value of goods and services produced.

-

It must be a surprise to the reader, but the findings, rankings, and recommendations of each study differ significantly. In essence, four business climate studies, sharing a similar view of the world and which value high-tech industry highly as an economic development objective, arrive at disparate conclusions and recommendations–and, needless to say, rank different metro areas differently.

On top of this cacophony, Chapple et al construct their own definition of high-tech, based on “the scientific and technical composition of the workforce in an industry” and which included selected BLS Occupational Employment Occupational Codes, pertinent to their conception of high-tech, to construct an I-Tech Ranking. Using “net new jobs” derived from 1991-1999 BLS employment data, they selected the 30 top growing SMSAs on the basis of “greatest absolute job growth” as opposed to “highest job growth rates” (p. 12, p.15).

Preferring I-Tech as a better measure of high-tech and innovation, they then proceed to (1) uncover a different set of high-tech SMSA [the largest metro areas by and large],suggest a different economic development strategy (based on the differential “resilience” of their tech-heavy SMSA, and then compare their findings to their other four studies discussed above–and find significant differences. They conclude, indeed their last sentence is: “For this reason alone, further research is badly needed” (p.27).

First, the reader should realize that Chapple et al’s article and the commentaries were published to serve an underlying purpose of demonstrating the overwhelming problem common to all business climate rankings: how does one actually define the concepts one is measuring and how does definition affect the rankings and the recommendations. Arguably, the point of the three articles was to demonstrate that definitions and data sets matter, and they do affect the findings. Implicitly, the articles demonstrate that the definition of the concept employed in the business climate-study-rankings matters very much and CANNOT be ignored by a reader. Definitions of high-tech affect the strategies recommended and the rankings themselves. [We said it three times for the normal mind, as my mother would have said].

Practitioners should not put too much weight on any ranking system, but instead should work to develop detailed knowledge of their region’s special economic niche and to develop relationships and strategies that build on established strengths.

To this Cortright responded, in part, [remember his ox had been gored by Chapple et al]

Debates over the merits of competing schemes for ranking metropolitan areas as high-tech centers shed little light on the important policy questions that should be the core of economic development policy. There are no strong theoretical reasons for preferring one ranking system to others. Rankings often conflate different industries and ignore history, obscuring the varied and often idiosyncratic processes that drive growth in different regions. Although an occupational perspective is a useful one for examining economic activity, it is a supplement to, not a replacement for a careful understanding of metropolitan industrial specialization. Practitioners should not put too much weight on any ranking system, but instead should work to develop detailed knowledge of their region’s special economic niche and to develop relationships and strategies that build on established strengths. (Abstract for Joseph Cortright’s commentary, p. 34, of Chapple et al)

So in conclusion, the articles/commentary vividly provide considerable support to the notion that there are many valid ways to define high-tech (the concept relevant to these articles). Whether one or another definition or data set is superior is very much dependent on the user’s purpose and perspective. From the perspective of the Curmudgeon and the approach he is taking in this review, it is further evidence that climate and ranking studies are far from objective or neutral–they are not simple mathematical and statistical derived reality. They reflect a point of view, perhaps organizational purpose and an ideological value system. And now we know that business climate studies that share the same world view and economic strategic approach can also differ widely.

Business Climate Revisited: Our Takeaways

Despite our persistent whining and downplaying of state business climate,as it is treated in blogs, Think Tanks and the overall professional literature, the reader should not draw the conclusion that business climate as a strategy or concept is worthless–not deserving of our attention. Just the Opposite!

The Curmudgeon believes state (and national) business climate is very real and it matters to economic development. We need to better understand how business climate governmental decisions are made and how these policy changes affects private sector decisions and what are the reasonable outputs. Without that understanding we cannot select the indicators we will use to evaluate the effectiveness of business climate in affecting the complete range of private sector outputs. We also must always keep in mind that state business climate is not just affected by one policy area or one set of policy changes–but is set by literally hundreds of policy areas and policy changes and the past legacy of policies.

At its fundamental essence, business climate is about incentives and that usually takes the form of cost-minimization and to a slightly lesser extent, tax abatement. As we have reported in this article, quality of life business climate has been harder to prove through aggregate research. School systems and infrastructure must create benefits, but benefits are hard to track using a business climate methodology which is an offshoot of cost-benefit methodology. Costs and their effects are easier to measure. That means that, whether it means anything or not, lower cost business climates will be easier to prove valid than quality of life business climates–especially in short of intermediate time frames.

This is particularly true in that, as we tried to point out, the decision to relocate a firm on the basis of factors associated with business climate is much less rational than rankings and the current business climate claptrap assume. The uncertainty, the time lags, and the failure on the part of both parties (state government and relocating firm) to understand the assumptions and quid pro quo of the business climate transaction. Firms may relocate, but once in the state they often respond in ways unanticipated by the proponents of the business climate initiative. Some business responses are desired, others not so. Governments (and researchers) often have very specific goal objectives (which are usually unrealistic to begin with–job creation for instance) while the firm is more likely to appreciate its “total” contribution to the community rather than any one specific goal. Existing methodologies do not capture (and they probably never will) capture the multiple outputs of a related firm. Specifically, to the extent that rankings are based on jobs created by a specific set of policies, the more likely the ranking is to be misleading, if not deeply flawed. As a consequence, as the studies we have reviewed confirm, rankings correspond poorly to actual economic growth in all its forms, ratings disagree among themselves even if they are trying to measure the same thing, and the while specific rank of a ranking system may slightly vary from year to year, the same states excel for decades.

But all this does obscure our core message: in the real world today business climate has degenerated into an ideological war, red versus blue if you will–and the literature reflects that war. Indeed, the literature is the main battleground of that war. Unless you are a willing participant in that partisan struggle, why waste your time?

Comments

Wow! In the end I got a website from where I be able to really

obtain useful facts concerning my study and knowledge.

Comment by Fae on September 24, 2014 at 1:35 am

Trackbacks

The comments are closed.