Those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it–mistakes and all.

American state and local economic development history (S&L ED) is largely unknown to many contemporary economic developers. To the extent we have a professional history, it is smushed into an abbreviated and distorted three “WAVE” paradigm” that itself has been distorted by the fog of time.

In that paradigm, modern” (post-industrial Third Wave) ED is a new era vastly different from anything previous–a brave new world of knowledgeable experts, government-led ED, and slightly anti-capitalist. The First and Second Waves, led by chambers of commerce, consisted of dilly-dilly boosterism, stealing firms from other cities/states, ignoring the plight of workers, immigrants and Blacks–and MOST IMPORTANTLY– failed to understand the centrality of INNOVATION, CREATIVITY, KNOWLEDGE-BASED EDUCATION and TECHNOLOGY as the wave of the future.

Heavily-laced with inappropriate, unnecessary, ineffective and immoral business incentives, the first two waves passed into history, replaced, for an equally unknown reason, by the heaven-sent Third Wave. Third Wave economic developers prided themselves for discovering innovation, “the entrepreneurial city and state”, technology and startup gazelles, venture capital–and more. The great EDOs of the Third Wave were government, nonprofit and universities. Private EDOs were thrown into history’s trashbasket.

The reality presented in As Two Ships is these Third Wave strategies previously existed, and were amply used in the 18th and 19th centuries. Government and nonprofits were major players eons ago, long before the post-industrial age. Moreover the industrial age never has left us; we simply call it global competition and advanced manufacturing. Chambers still operate and offer substantial ED programs and strategies–as do Tourist Promotion Agencies, Workforce Agencies and a host of non-Third Wave EDOs. The First and Second Wave “DEAD”–are still walking.

“Post-industrial” economic developers simply retooled/renamed several hundred year-old existing ED tools/strategies, formed new EDOs, and devised new jargon and thousands of pages of legitimizing theory, concepts, and algorithms–to fit their “modern” world view. Digits, its seems, don’t need widgets. Apparently, creativity also includes reinventing the wheel. UBER has replaced taxi cabs and dispatchers and the “gig economy” or “shared jobs” sounds lots more attractive than a “second job to pay the bills”. The point I make is the Three Wave History has a bit of self-promotion, if only by diminishing the role and struggle of those who preceded us.

This online history of S&L ED asserts proudly we rest firmly on the shoulders of those who worked in our shoes decades and even centuries ago. Having said this, who has the slightest idea who preceded us? Scary names like Robert Moses, maybe Jane Jacobs populate the ED ghostyard. The first we love to hate, and the latter we love because we have consciously distorted her message and actions. As for the 19th, and perish the thought, 18th century–well economic development didn’t even exist–that’s why we have the Three Wave History in the first place. It puts a nail in the history coffin so we don’t have to waste any time with it. A three-hundred-year history is not simply a short walk through a graveyard during Halloween. It’s more scary!

The problem with a three-hundred year history

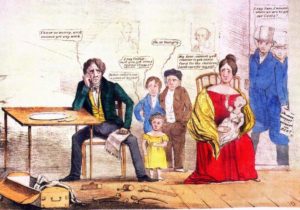

It overwhelms us. There is too much of it. Past economic developers wore different clothes and didn’t use the correct jargon. They were often politically-incorrect. Worse, our history is often not what we think it is; a lot of it doesn’t fit into our current perspective–and we usually don’t like that! Besides I never took a history course, and “dead white men” are really out of style these days.

How do we deal with these problems? Like we eat a pizza–slice by slice, bite by bite.

First things first, let’s break down the bulky history.

As Two Ships reconverts two S&L ED historical realities into themes that “break down” the accumulated mass of history into manageable slices and bites. The two organizing themes were (1) a temporal classification system called “Eras”–that included within each Era thematic sub-time periods labeled “Ages”; and (2) the recognition of America’s three macro-regions, North (New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwest), South and “West”. Each were settled by different ethnic/racial groups in different time periods, possessed unique histories, political cultures and congruent policy systems, and evolved local/state economic bases during different stages in American capitalism’s evolution. Theme 3 will set up our regional approach with modules focused on southern and western S&L 19th century ED.

Theme 1 introduces American ED’s four “Eras” (leaving “Ages” to another day). As Two Ships collapsed time into four “Eras”:

- pre-Civil War “Early Republic Era” (1790-1870);

- “Big City” Industrial Hegemonic Classical Era (1870-1975);

- Transition Era (1975-2000);

- present-day Contemporary Era (post-2000).

The published book deals almost exclusively with the first three. A second and third volume expanding on the Transition Era and Contemporary Eras, loosely sub-titled “Reinventing American ED” and “Twilight of Growth“, are well-advanced.

This “Eras of American ED” topic is dispersed into three modules–this module being the first. This introduction shortly moves onto discussion of the “Early Republic Era” and when completed will present a link to the next, Classical Era, and at its conclusion another link will connect the reader to the Transition Era and an initial introduction to our present-day Contemporary Era. The Contemporary Era will be more fully developed when it is formally presented in its own set of modules.

Early Republic Era (1790-1870)

The Early Republic Era is the least known and usually perceived as the least relevant. That’s a major mistake. The Early Republic and Gilded Ages (19th Century) witnessed the development of northern industrial Big Cities. That’s where/when modern American state/local ED really started. By the end of the Early Republic–certainly the Gilded Age–Era, the framework and basic structures of our Contemporary Era’s fifty state ED system were firmly established.

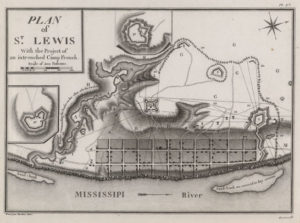

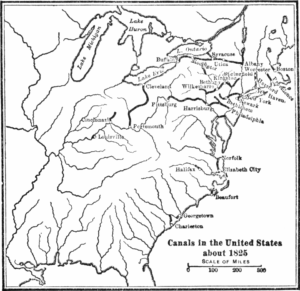

Industrial capitalism developed during the Early Republic Era. During Washington’s presidency, there were only fourteen banks in America–all, save the Hamilton national bank, were state-chartered. There were no canals, steamboats, or railroads, and no road or bridge system to connect the states, or even the cities within the states. Salem Massachusetts, my home town, was the nation’s seventh largest city (7,900). Its custom duties supplied a great deal of the federal budget. Commercial goods got from one state to another principally through coastal commercial ships. States were isolated and trade/travel was a semi-hazardous, expensive and time-consuming affair. Let’s not even talk about the nation’s vast interior. Lewis and Clark were more than a decade in the future. Under Washington and Adams, France owned a great deal of the North American continent–part or all of fifteen American states (828,000 square miles, triple the size of the thirteen original states).

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase–and the War of 1812, followed by the formation of the Texas Republic, the Mexican War and the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain and “Seward’s Alaska Folly” were all events during the Early Republic–as was, BTW, the Civil War. The point is that during the Early Republic most of the cities we now live in were founded, incorporated and formed their economic bases. City and Economic Base-building is the first, obviously, strategy of an economic developer. They built from scratch, deep in the American wilderness. We still build cities, but it is a lot easier now. What about a city’s economic base? Who and how was that “built”

New cities needed (1) to be built (urban development/city-building) and older cities (2) needed to modernize (redevelopment, CBD urban renewal). Boston’s first urban renewal project–redevelopment of a deteriorated waterfront, a 1742 marketplace building (Faneuil Hall), and adding to it the first Quincy Market–occured in 1826—Mr. Rouse’s present day version was late to the game–actually the third redevelopment of downtown Boston.

In this Era most of our Eastern (and San Francisco) cities were established, the eastern Midwest was settled and Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, Kansas City, and even Minneapolis were founded. Industrial capitalism incrementally grew and new industries, sectors, and new forms of industrial technology were the fuel for for Early American ED municipal economic bases.

As Theme 2 will describe, industrial capitalism developed slowly and incrementally during the Early Republic–and exploded in the Gilded Age. Manufacturing was the technology of the day–railroad locomotives were the rocket ship of the Early Republic. Canals were the highways. Steamboats the first freighters. Stagecoaches the first trucks. Industrial capitalism was never a “perfect” economic system–and it didn’t take long for reformers to call for changes in it, and help for those disadvantaged by it. The first , second, third wings of American Community Development were each “founded” or were “born” during the Early Republic–and the fourth and fifth during the Gilded Age. In short by 1900, community development was already almost a hundred years old. That story will be told in Theme 2 mostly, but also in Theme 3.

The need for infrastructure was huge–and that turned out to be a primary task of American ED. To develop infrastructure meant fostering innovation and assisting Early American entrepreneurs, while mitigating the disruption caused to the dominant national agricultural/trade economy. Tariffs and protectionism were top issues on the national agenda. Sound familiar? Theme 2 will spend considerable time on infrastructure that “connected the urban dots”, the new cities that formed in the interior wilderness. Connecting the dots was the first task of something I call External-Mainstream ED–to be explained in Theme 2.

A second task was for each community-city-state to facilitate new gazelle-like sectors and industries that developed after 1800. Known today as “manufacturing”, textiles (clothes, shoes, and machinery) were the first, but alongside were farming/food processing machinery, chemicals, machine tools, transport modes (Tom Thumb locomotive), energy and communication equipment, and steel (requiring coal). America, like modern day Japan and China, stole a great deal of technology (from England).

Without an domestic American finance system in place, England provided most American commercial financing–until the War of 1812. That largely unknown war jump-started American state and local (S&L) ED. America needed to find new ways to fund its emerging expanding agricultural production, and manufacturing and infrastructure-related technologies. That turned out to be the first major task of American ED. Over the next several decades, EDOs/strategies such as the first public/private partnerships, as well as VC-equivalent instruments, startups financing, tax-exempt bonds/loans to business, municipal/ state business creation/retention (using tax abatement) strategies were fabricated. Tourism flourished during the Gilded Age–Atlantic City was the trailblazer. The annual reunions of the Union Army constituted the backbone of the early convention center strategy. Also, let’s not forget about early suburbs–they were already resisting the encroachment of large eastern “Big Cities”

Early ED strategies were produced by municipal/state policy systems created by the State. First Settlers, the authors of constitutions/basic laws/municipal charters. These Early Republic “First Settlers”, were “nativist” American, as sizable ethnic/racial population movements occurred later around the Civil War and after. The published book spends considerable time explaining how their religious-derived political culture was injected into Early Republic Privatism and Progressivism (our Two Ships), transported to the Mississippi and cemented into urban/state constitutions/charters, and policy systems. From these policy-making structures came the first EDOs, strategies, tools, and programs of American ED.

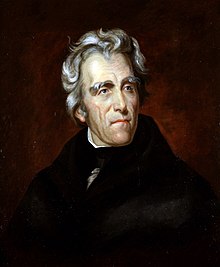

Enter a Black Swan. American ED was profoundly reshaped by the Jacksonian populist victory, and a crippling depression, the long-lasting Panic of 1837 (extending into the 1840’s) that followed. The previously dominant Early Republic EDO (the state-chartered corporation) was linked to infrastructure bankruptcies, conflicts of interest, legislative ineptitude, and serious corruption. Huge tax increases to pay off their debt triggered a series of state”reform” laws across the nation over the next decade. Today these laws are known as “gift and loan clauses“. They (along with something called “Dillon’s Law”–1868) laid the cornerstone for each state’s future public/private partnerships and firmly cemented a diverse fifty-state decentralized system of American S&L ED.

The uniqueness of these clauses to each state, shaped that state’s “style” of ED ever after. Why? Nineteenth century economic growth meant economic developers had to work with the private sector, and that meant ED strategies and EDOs had to conform with each state’s unique gift and loan clauses. The series of hybrid “quasi” EDOs that resulted (including railroad corporations, municipal boards and commissions, old-style port authorities,franchises, and utilities) built the Big Cities of the North and Midwest. Each State’s unique “gift and loan clauses precipitated a similar uniqueness in devising subsequent “bypasses” to the gift and loan clauses. These two dynamics evolved over the next 175 years to produce today’s decentralized, variegated and competitive fifty-state American ED–exposing, BTW, the centrality of First Settler political culture to contemporary ED policy and strategies.

The post- 1837 Panic reaction hardened into a policy cement when ,in 1868, an Iowa judge, John Dillon, decided that “cities were creatures of the states“–and the national Supreme Court decided to not challenge that decision, but rather to impose it (by default) on all the states. This cultural-legal legacy of each state insulated it from its neighbors–and allowed each state to define how, and for whom each ED strategy, tool and program would be used–or not used. ED strategies, tools, and programs with the same name or title were used for different purposes, favored different constituencies–or remained largely unused in the state’s quiver holding its “ED arrows”.

The Early Republic evolution poured the foundation for our Contemporary Era’s state-centered business climate competition, and cemented what had been a diverse set of state reactions to a severe depression into a decentralized and idiosyncratically varied fifty-state American economic development “system”.

Theme 2 were concentrate on Early Republic, and some Gilded Age economic and community development. Theme 3 will finish up the job–concentrating on the South and West. By the end of Theme 4, we will literally be “cooking with gas” and talking on the phone, riding subways, and working in CBD skyscrapers. During those incredible, totally awesome” years we will be living in the second of our four Eras, the …

“Big City” Industrial Hegemonic Classical Era (1870-1975)

(Click to connect to Next Module in Current Theme)

QUICK ACCESS NAVIGATION (Click Below as Desired)

MAIN ONLINE HISTORY MENU (connect to another theme or module)

JOURNAL OF APPLIED RESEARCH MAIN MENU

General Menu and Table of Contents