The Transition Era (1975-2000)

The Transition Era (1975-2000)

I named this time period the Transition Era because that is exactly what these twenty-five years were.

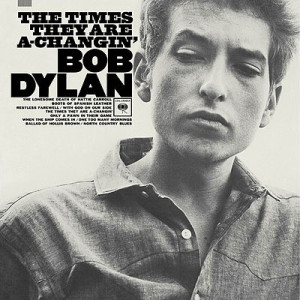

I lived and worked professionally during the entire of the Transition Era, and I confess that I always sensed the times were still a’changing–that we were always reacting to something or another. It was not until after the turn of the century did I suspect we had evolved into a new ED “world”. But for now, let’s stick with the Transition Era.

The problem, for me at least, in using the moniker “transition” is that it implies movement “from” and a movement “to”. That is we “pivot” from one form or structure of American ED to another. Honestly, I am not sure that either implication is accurate. I strongly believe, and my research supports Contemporary Era reality that the past continues, coexisting with a new world that evolved during the Transition years.

What strikes me more about the Transition Era–and the Contemporary Era thus far–is that the Early Republic Era seems shockingly relevant to what is going on at present. That time period was one in which systemic change and economic evolution was ongoing–and disruption, as well as innovation cast a peculiar unsettling tenor to the times. I also know how that turned out–and it wasn’t pretty. In short, I open up the possibility the Contemporary Era is a misnomer; we may still be in the Transition Era. Something new is evolving, we are heading somewhere, but I confess it is not yet unequivocally clear as to where. What is equally obvious to me is that underneath that new world, the old one endures. I also firmly believe that ED is a “tail”, not the “dog”. We react, no matter how much we think we “create”, the more accurate reading, in my perspective, is that we “react”. A little humility is always good.

That is why I think understanding our past, and fully appreciating the drivers behind our policy and strategy is more important than ever. The past will integrate into our future. History “is”–not “was”.

So how does this module deal with the Transition Era to 2000?

The first is to outline the key “events” that happened during these years. The second is to point out the key underlying dynamics that channeled us, i.e. we reacted to, sometimes unconsciously. Both dumped us unceremoniously into the Contemporary Era.

Events and Dynamics of the Transition (and Contemporary) Era

“Bob Dylan – The Times They Are a-Changin'” by Source. Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bob_Dylan_-_The_Times_They_Are_a-Changin%27.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Bob_Dylan_-_The_Times_They_Are_a-Changin%27.jpg

The events are (1) the Great Society and the Reaction to it; (2) Deindustrialization and the amazingly-named twenty-year Great Reindustrialization Debate; (3) the capitalist rotation of sectors and industries (i.e. we may be in a “post-industrial” world, but that does not imply the end of manufacturing anymore than manufacturing replaced transportation/communication sectors); (4) from which emerged “the Contemporary Era Paradigm”; (5) Regional Change–the collapse of the Hegemony; (6) “victory” of the suburbs and a new metropolitan configuration (the “birth” of the metropolitan area); (7) the Rise of China and the Emerging World–a new competitive global hierarchy; (8) rise of State-level MED/CD challenging, perhaps replacing, the Classical Era local-municipal leadership of state-local ED; and (9) immigration and environmentalism/climate-change/quality-of-life as disruptors of political culture and policy systems and which have redefined the priority and meaning of economic growth as the principal goal of American S&L ED.

The underlying dynamics relevant to the Transition Era are, at minimum (there are more):

(1) continued evolution of American capitalism into global oligopolies, rise of transnational one percenters (corporate elite), the coexistence of startups with global corporate behemoths, with the rest a beleaguered middle;

(2) consequences of sector rotation from manufacturing to IT, Internet, to Digitization and Data-Driven policy-making–and the “hollowing out” of working, middle, and professional classes–and the places in which they live–simultaneous with massive volumes of new entrants from immigration;

(3) incredible multi-class affluence and its effects on a succession of generational cohorts yielding a politics of affluence which, among its many implications have led to the rise of Third Wing Community Development and the stagnation of the previously-pivotal Second Wing (see the “What is this Two Ships Thing” modules that come next), injecting considerable instability and polarization into local, state and federal policy systems;

(4) an ongoing evolution of a post-Bretton Woods, post-Cold War, post American Empire, global economic system and the development of a multi-polar nation-states contesting–or checking–the post-WWII Bretton Woods-Bipolar regional/transnational world order and economy.

(5) all of the above placing considerable stress on state and local policy systems who lack the scale and resources sufficient to deal with this turbulence and disruption, yet are frequently tasked by federal deficit-ridden, stalemated and polarized policy-makers to manage disruption and bushwhack a functional path for their respective citizens and residents. In this turn to a hopefully resilient federalism, local and state economic developers will no doubt participate in policies, tools, and strategies which can restore economic stability, a level of economic growth, or at worse manage decline. If so, it couldn’t come at a worse time professionally, as …

(6) during the Transition and Contemporary Era, the prime professional trends has been to (a) siloization into incredibly minute policy, program, and tools specialization, supported by micro-professional associations and NGOs/Policy Institutes/Foundations and a horde of profit and nonprofit consultants/site selectors—the ED equivalent to the military-industrial complex, and (b) a state/local policy system and policy processes which have become dysfunctionally politicalized, institutionally-bankrupt, centered around charismatic gubernatorial/mayoral administrations and legislatures/city councils unable to sustain policy over the period of time necessary for it to be successful. In this schizoid siloized atmosphere, the gap between American ED’s Policy World, and its Practitioner World has never been greater.

OMG–let’s collectively slit our wrists. How negative can one be? Isn’t anything going right? Were the Transition (and Contemporary) Eras really that bad?

Not-at-all. Wealth generation and accumulation, for example, has been cited above as producing a politics of affluence. Unemployment is very low. The stock market is up a lot. We still can bomb almost anyone we care to. There are still two vast oceans between “us” and “them”. People from across the globe still flock to us to live and work. Our policy systems “look terrible”, their sausage-making amply reported by a free and irresponsible press, still manage to produce policy and mail my social security check on time. Facebook, Google, Whatsapp, Twitter and Youtube provide meaning and value to our personal lives.

But the Transition and Contemporary Eras one can reasonably argue have been driven by events and dynamics that ensure we cannot return to the Classical Era, but offer little guidance (except for that very special guru and expert/leader each one of us believes understands what is going on) as to what tomorrow will be like. So let’s take one step a time and let’s take a look at some “specific” changes to American ED occurred during the Transition Era before we proceed to introduce the main events of the Contemporary Era

Specific Changes in American ED during the Transitional Era

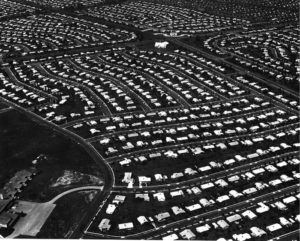

During this period we discovered decline–and growth–in so many ways. Classical Era suburbanization picked up steam–by 2000 more Americans lived in suburbs than anyplace else combined. Suburbs left in their wake the so-called “legacy city” a fiscal, employment and demographic shell of the former hegemonic Big City. Not to be outdone, the Big City industrial base had deindustrialized. Manufacturing already suburban since 1940, shuttered its doors.

Given that Big City dominance rested on its manufacturing base, deindustrialization, while national, impacted the more mature manufacturing of Big Cities. MED redefined itself targeting “advanced” manufacturing, but most of all the new gazelle–technology in all its forms and sectors–and nudged us into strategies called knowledge-based economic development, geographic targeting, export, and a host of others. Hegemonic Big Cities refocused MED toward “job creation” (mid-1980), giving up on stopping population outflows.

The West and South paid little attention to these former-Big City goings-on. A new regional pattern developed from the vacuum created by the troubled northern/Midwest hegemony. Sub-regional patterns developed; the New South alongside the Old South, Texas and the energy southwest, central states lost visibility, and mountain states discovered skiing and tourism–the Pacific states skyrocketed. Still at war with Russia, China and Vietnam–and coping with a transformed Japan/Germany, manufacturing.

With some sectors clearly stressed, other young defense/technology-oriented and manufacturing (in the West and South especially) exhibited hyperbolic innovative growth alongside a vibrant “service” (FIRE, tourism) economy offered jobs to encourage in-migration. Traditional low-tax and right-to-work business climate proved especially attractive. Hegemonic Big Cities, fiscally exhausted, hemorrhaging middle class and the young, engaged in its own “great civil war” between white and black during the Transition years, and settled down affably in the Contemporary Era. Now we talk about gentrification.

So Sunbelt growth blossomed and former-hegemonic Big City states declined until the 1990 when the latter stabilized due to the heroic efforts of a series of “charismatic” mayors that repurposed CBDs and restored fiscal stability. The other former-hegemonic story was the rise of its African-American CD wing, subsidized by new Great Society federal programs, anchored in its distressed neighborhoods and rising central city political power. As Big Cities looked inward, the former-hegemonic States, led by aggressive governors, filled the gap–offering fiscal aid to the cities (and school systems) and embarking on relatively aggressive hybrid ED/CD strategies that increasingly relied on depressed area targeting, knowledge-based innovation/entrepreneur and cluster development strategies. Strong export, FDI, and broadly-defined technology attraction strategies also were common. That “paradigm” lasted until the Great Recession.

Each of these above strategies were fabricated during an almost thirty year Policy and Political World “Great Reindustrialization Debate”. That “debate” laid the foundation for 21st century Contemporary Era policy paradigms. Initially, our chief enemy was Japanese manufacturing. Out of the Reindustrialization debate poured a host of new strategies ranging from workforce, to universities, to radically shifting industry sectors targets and making a cult hero of “clusters”, Silicon Valley, Zuckerberg-Thiel, and Internet. Taking their own sweet time, new strategies incrementally evolved and formally “jelled in the late 1990’s. These strategies became the core 21st century Contemporary Era paradigm.

Central cities balanced neighborhood revitalization with CBD/waterfront (entertainment) redevelopment. By the end of the Transition Era, former Big City geographies had evolved new policy systems, in which minority areas and warring neighborhoods in transition and distress were increasingly impactful. MED became secondary (aside from attraction) and consciously or subconsciously private/hybrid/nonprofit EDOs assumed responsibility for the jurisdictional economic base.

“NWAJeffcoSheriffSign” by Xnatedawgx – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NWAJeffcoSheriffSign.JPG#/media/File:NWAJeffcoSheriffSign.JPG

CD, on the other hand, centered in neighborhoods, and when CD-prone hybrid mayors and governors took over, they experimented for twenty years to fashion a working MED-CD agenda/policy and administration process that satisfied few, especially the all-knowing Policy World, but somehow achieved a measure of success, or simply outlasted decline until stabilization and reversion to the mean set in. More and more, however, Second Wing projects led to nowhere–and Third Wing, from ACORN to OCCUPY, and a thousand ethnic/racial-based movements poured into the streets, airwaves, and smartphone digits.

Americans were still mobile in the Transition Age. After 1970, spurred by legislative reform, huge numbers of foreign born immigrants piled into our cities/states. California, Texas and New York (City) did especially well. A sizable generational migration, followed by succeeding generational migrations altered the regional cultural and demographic composition. This generational migration coincided with a new view of “growth”, growth management, quality of life, and something called “environmentalism” redefined–and some would say confused–the profession’s sense of direction and purpose. Whatever it was, economic growth in 2000 was not your grandfather’s economic growth. No Growth was a respectable alternative, if not preferred. No one in the United States liked capitalism any more–at least publically.

City-building and simultaneous suburbanization (suburbs and central cities autonomously and simultaneously grew) differentiated Sunbelt ED and its demographic landscape from its Eastern predecessors. With considerable “Big Sorted” population growth, city-building (retirement communities, master-planned communities, condo associations-Privatopia and unincorporated “communities”) developed vast geographies composed of new types of policy systems–expanding the thematic focus of American sub-state ED. Nowhere was this more evident than in California, Texas, Arizona and Florida which were fueled by large numbers of Hispanic immigrants, legal and otherwise beginning in the early 1970’s and picking up momentum with each passing year. The “bottom” of of our bottoms-up S&L ED changed massively during the Transition Era.

The cumulative effects of these agents of change on state and local policy systems was transformative–and disruptive. The South and the West of 1970 was no longer the same in 2000. If the hegemonic states were coping with decline, stagnation and demographic/policy change, ED associated with growth and change was not easy either. In those states also, states played a much larger role than ever before.

Seemingly out of the blue, states gradually entered into sub-state ED in a meaningful way. Developing their own configuration of strategies and programs, some states rode herd over local ED–others simply joined with the locals, each playing in their own ED playground. The diversity of state-level MED/CD response was truly amazing–matched only by the an equally strong movement at the neighborhood level. The Federal Government had pulled back domestically from direct ED programs, and had in turn moved to a new playground, the American-dominated global economy/politics.

Domestically, instead of urban renewal, housing, or Great Society-type domestic programs, the Feds stressed environmental and growth management regulations by new federal agencies such as EPA and DOE. A Sagebrush War erupted, alongside a hyperbolic state-led incentive war for political correct targeted firms and clusters. Business climate competition was ever more intense. The old Classical Era “stuff” re-functioned as well. First/Second Wave chambers led regionalization efforts, one-stop-shopping and policy advocacy, as well as CBD redevelopment, tourism, workforce. Whatever else it was, no one can accuse Transition Era ED/CD of being dormant, asleep at the switch.

Community development exploded. Several CD strategies caught on like wildfire in immigrant and Great Migration central city neighborhoods. Neighborhoods emerged as a primary site in which to conduct ED/CD–so did CBDs. States experimented to fabricate a CD agenda that fit addressed state needs and politics–displacing and modifying significantly the implementation of MED (and Privatist) strategies and tools.

CD and MED drifted apart into separate professional complexes. An immense gap opened up between practitioners and policy world economic developers. Never had Progressive and Privatist ED been so hostile to the other–and their strategies, tools and programs so zero-sum. The path to Contemporary Era Red/Blue polarization was blazed and bushwhacked during the Transition Era–a path that would transform the practice of American state and local ED maybe forever.

New strategies, tools and programs prompted a bewildering variety of CDOs/EDOs and professional specialties. The robustness and vitality was not all to the “good”, however. It led to “Siloization” the establishment of multiple professional associations, a consultant-NGO-think tank “complex”–all of which destroyed whatever little coherence American state and local ED had as a policy area and profession.

The MED/CD that emerged from the Contemporary Era was incredible decentralized, with large numbers of practitioners almost isolated in small non-large city/suburban/central city EDOs, and an increasingly swelling horde of new practitioners/consultants populating incredible, to the point of mind-numbing, number of strategies, sub-strategies-programs-tools, and methodologies. If one yelled “economic development” in a crowded theatre one was never sure if no one would stand up, or everybody would.

Everybody, it seems was doing ED, but “their ED” was narrow, specialized, expert-rational–and those not in one’s own particular ED cubicle-niche–silo were often not thought of as professional compatriots. In thirty short years, the Classical Era had been relegated to the dustbins of ED history. Symbolically, by the end of the Era–and century–the Y2K potential catastrophe was in the front of our mind as the ball fell in Times Square. Nothing happened except the Internet took over and politics and the American economy of the 21st Century Contemporary Era–and American ED–were playing losing game of catch up in the new economy of innovative disruption, knowledge, and hordes of immigrants. If we had known our history better we would have realized we were close in spirit and plight to our Gilded Age predecessors.

But then abruptly, precisely at midnight December 31st, 1999, it was over. The great Y2K apocalypse yanked American ED from debate, research, and experimentation into the hard real world that is the present-day Contemporary Era

An Intro to the Contemporary Era (post-2000)

(More to Follow in Later Modules)

Transition Era change resembled in many ways the “end-product of our “boiling frog” metaphor. For better or worse, by the turn of the century the dynamic elements of the profession and policy area stabilized into a more or less durable professional/policy system “order”, shocked and “disordered” by the Great Recession, has oozed, drifted, shoved, and simply let itself be pushed to the sidelines–marginalized by great global forces, polarization and partisanship, and multiple cohort generation change–and lots of new immigrants and tons of refugees. In the process ED had become a church “of what’s happening now”, fearlessly confronting an Internet Age, social media, and populism.

The Contemporary Era was bifurcated by the Great Recession, which has as all things seem to do in the Contemporary Era, also passed into the fog of history. Nothing, no issue , topic, or concern seems to stick more than five days since those Recession years.

Key elements of the current Contemporary Era include:

- A contested ED “landscape” emerged with CD and MED slugging it out, in a thinly-veiled Privatist-Progressive struggle with strong “growth vs. decline” undercurrents. Both wings lost almost all connection to each other with MED basically ignoring CD and CD contesting nearly all strategies and tools employed by MED practitioners. The almost-still-born Great Recession recovery so fragile it weakened the consensus supporting (Great Reindustrialization Debate) economic theories that were the foundation for many Contemporary Era ED/CD strategies and programs.

- The Contemporary Era ED landscape exhibited a reluctant, grudging acceptance of suburbs and regional change as a fiat accompli. ED players redirected attention toward “metropolitan areas”, regional one-stop-shopping, university-driven ED, and multi-jurisdiction (regional) clusters–some even talked of mega cities. These region-wide initiatives, however, could not escape realities of jurisdictional chronic decline (Great Lakes) and hyperbolic, “trees grow to the skies” Silicon Valley-ese new economy growth. Metropolitan areas quickly divided themselves into two more or less stable patterns of growth and stagnation (if not decline). The Contemporary Era strategy paradigm called for stagnant metros to copy the success of growth metros. Growth metros themselves were divided between Privatist (Red) and Progressive (Blue) strategies.

- In the Contemporary Era ED and CD flourished at the neighborhood, municipal, and even regional levels–each operating in its own strategy and program space. Above these levels floated a newly-energized state-level MED/CD apparatus. State ED/CD led (mostly) by gubernatorial administrations that incorporated MED/CD into their electoral coalition and policy agenda. This politicization of state-ED was best expressed in the constant and pervasive incentive wars among states, with locals as junior partners.

- CD’s rise and downtown fragility fostered a host of new sub-municipal EDOs that autonomously operated beneath the city-wide/regional governmental/chamber arena. In many jurisdictions, these sub-municipal entities were where the action was, bringing citizens and activists into the MED/CD policy-making process. New municipal level policy systems emerged. At the municipal level many government EDOs developed hybrid CD/MED strategies. In many “Blue” states municipal government EDOs embraced Progressive CD strategies, while private city-wide EDOs autonomously pursued Privatist MED strategies–each oblivious to the other.

- Contemporary Era strategy robustness also meant policy complexity, fragmentation, as well as professional siloization and incoherence. CD/MED divergence triggered an associated gap between “on the street practitioners” and the theoretical-ideological policy world. The two dynamics reinforced by successive generational changes, more-often-than-not resulted in a endless parade trendy strategies and programs divorced from actual performance and reduced to rhetoric and data-driven analysis that floated way above the policy process. For all practical purposes, economic developers rhetorically chased the same “correct” industries, sectors and occupations/skills–using their version of the acclaimed strategy/ program du jour.

- In the process we discovered yet new unsolvable problems such as legacy cities, Two/Luxury Cities, gentrification, social justice as now “white privilege” and anti-corporate resistance, and what used to be poverty was now an impossible to define–or alleviate–inequality–an inequality that recently excluded “white non-privileged” Forgotten People. In essence, the end-goals of MED/CD had become hopelessly politicized, tied to the fortunes of media-hype electoral politics.

This last section will be so easy to criticize. All this bombast sounds so negative–in part because I “lead with my chin” and have deliberately selected the Contemporary Era’s controversial and contested features, not where it has worked well. But there is no mistaking America’s state and local ED was no longer your grandfather’s ED–and it has its problems …

And yet had American ED departed from its past heritage? Who Knows? Who Cares?

Will that heritage reassert itself? Will history repeat itself? Will we recognize it if it does?

There is a lot of water that has to flow through our historical river before we can deal with these questions. And so until the creek rises, let’s deal with them later.

Now we turn our attention to our Two Ships and Political Culture