The TWO SHIPS of American Economic Development

Most economic developers sail almost exclusively on one of my Two Ships. Amazingly, economic developers on-board the largest ship (called Mainstream ED), do not consider the sailors on the other ship (called Community Development) as economic developers–AND VICE VERSA. Why? To strain my maritime metaphor to the breaking point, they sail on different oceans. Essentially each ship is a distinctive “approach” to the practice of American ED. These “two approaches” are my proverbial “ships passing in the night.” When they do come into contact, things get messy.

What divides these Two Ships?

Several things, but foremost is (1) whether they feel comfortable with the then-current version of American capitalism, and (2) each has different goals, definitions of growth, and different constituencies. (3) Each has its own values, experiences, and priorities which evolved over time. (4) Each establish their own organizational structures: EDO or CDO–and iconistic programs. Each has their own set of strategies, tools, programs and career paths. The ED Policy World generally is CD-leaning. Academia attracts very few MED supporters.

Today each ship segregates into separate professional associations, have separate federal government sugar-daddies, yet some economic development organizations (EDOs) somehow include both. Their strength and influence vary by city, state and region, but each are evident in all cities, states and regions. Still, using gentrification as an example, it is a problem for one, and a victory for the other. Tax abatement–private sector incentives–is another fault line.

Both existed in 1790. The chamber down the street could easily be more than a hundred years old, and the (CDO) housing authority downtown is the offspring of a CDO first created in the 1930’s. There are some neighborhood CDOs that can find predecessors as early as the 1810’s. The earliest “modern” municipal government EDO I could find was established by compromise between Boss Tweed and the New York City Chamber. It still exists today as a department within a larger ED bureaucracy. The earliest CDOs were found at the neighborhood level and in the New England town government.

Why two ED approaches?

Each ship or ED approach draws from its own distinctive political culture. Each political culture holds its own set of values, policy priorities, distinctive vision of its “heaven” and worldview. In 1790, the political cultures of the time sprung from the different religious/ethnic/racial migrations, Each possessed a different vision of the community/economy they wanted to establish. These clashing political cultures are why my mother told me never to talk about politics or religion. They did not get along then, or in the colonial era (when I was born).

Because of political culture. no one mistakes Charleston South Carolina for Boston Massachusetts–in 1790 or today. Political cultures defy common sense; they can continue for centuries, even though their adherents wear different clothes, worry about different things, and text on the Internet rather than read the Bible. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

As Two Ships provides a name for each underlying political culture; Mainstream ED (MED) reflects a “Privatist” political culture, and Community Development (CD) a “Progressive” political culture. Warning! Be careful–don’t read your definitions into these labels. Like them or not, these are my labels and wait until I explain them.

Because each value system is found in each region, state and community–and sometimes in any single individual economic developer–most city and state policy systems evolved into a Contemporary Era hybrid policy system. Contemporary economic/community developers inherited this bifurcated hybrid economic development; it was in place when they cashed their first paycheck. In the Reddest and Bluest of policy systems, one can easily find strands of the other. For the most part, in any given period of time, one is dominant in each state or community–but this can change–or not. Still, I must confess, I have worked myself on both ships at different periods of my life; it can be done.

In the end continuity is the best defense or proof for political culture. Municipal and state political cultures have a lot to “say” about which approach to American ED is practiced in their community. A caveat. “Say” does not mean determine or cause; it more precisely means shape or influence. Other important stuff happens besides political culture.

Through most of my history, the Two Ships were not actually fighting, but they weren’t talking to each other either. For most of American history, the Two Ships did not agree with each other’s values and priorities, but they shared a basic comfort with American capitalism and economic growth. In early years both strove in their own way, to ensure capitalism’s stability, fairness, and growth. Even Saul Alinsky, a proverbial CDer, basically wanted a larger share of the pie, not a repudiation of capitalist growth. That began to change around the time of the Great Society (1964) . By the time we reach today’s post 2000 Contemporary Era, for all practical purposes the Two Ships are at war.

In my view that’s a shame.

More than that, the war prevents both Ships from achieving their goals. Working together they could easily recognize they are not inherently zero-sum opponents, but complementary players on the same team. One plays offense; the other defense. That is a bottom-line hope, probably forlorn, that underscores As Two Ships and this Introductory Course. I do not like this war, and when competing ships arrive at a port, I want them to play nicely on the dock.

The article below provides the necessary background to integrate political culture into ED policy-making. It will provide some explanation and address a few questions that naturally would occur to the reader.

Questions about Privatism and Progressivism (P&P)

Privatism and Progressivism (P&P)

In real life P&P operate on a continuum that shifts over time and even by policy. When all this P&P stuff first began, back in the 17th century, the values, beliefs and preferences usually reflected one’s religion. America was settled during, and shortly after, a period of religious wars which, among other aspects, sorted out groups of people on the basis of values, beliefs, worldview, and even a bit of personality tossed in. Religious/ethnic refugees settled in different waves, and different American cities/states. This was our first “Big Sort”.

P&P were major influences in the development of colonial state and local charters and governance. These colonial “governance structures” were simply carried over into the young 1789 federal republic. Indeed the current basic Massachusetts state constitution–written by John Adams–was initially passed in 1780. Over the years, secularization replaced religion, but again, perhaps amazingly, the choices between values, preferences and beliefs demonstrated considerable continuity.

P&P today is certainly not what it was in the 17th century, but the old divides are still pronounced, wearing different conceptual clothes and using different terms, but still boiling down to the same core differentiating distinctions of three hundred years ago.

To identify those values, preferences, and beliefs that affect the making of ED policy is pretty important to my history. While this online history will not dwell on P&P, As Two Ships, the book does. There are a lot of values and practices that differentiated the two macro-cultures, but in this online history I selected several which are most critical to state and local ED.

At its most simplistic level, the two ED/CD-related cultures separate on the basis of two core preferences: (1) how one perceives the American capitalist system/economy; and (2) whether the community as a whole, or the individual who drives prosperity and economic growth, is to be advantaged. I am also tempted to throw in a third, valuing the risk-taker, or protecting the disadvantaged.

MED assists the agents of capitalist economic growth: firms, businesses, owners, production, innovation–and to protect and defend their community’s economic base from the vicissitudes of normal capitalist competition. Progressives, on the other hand do not seek to help firms and businesses. Rather they struggle to improve/empower “people”, primarily disadvantaged people to enable them to compete effectively in the capitalist system. Progressives care not a whit for the productivity of the community economic base, except to ensure it serves/accommodates the needs of people, residents, and the disadvantaged.

In a nutshell, MED’s primary target is a firm or business, and the “people” for a community developer.

The Centrality of Capitalism to the Bifurcation of American ED

What really lies at the core of our two distinctive ED policy-making cultures is their perception of the capitalist system. Privatist MED and Progressive CD ultimately represent different approaches to how state and local policy systems react, foster, and deal with our national economic system.

Two hard realities might be mentioned at this point. First, America has been, and still likely is, a capitalist economic system. In that American S&L ED is necessarily tasked with linking and protecting its jurisdictions and communities within that capitalist system, S&L ED must operate within capitalism’s broad confines. That is MED’s primary task. Secondly, capitalism is not a static system. A currently best-selling business tome entitled “the Fourth Industrial Revolution” bespeaks its constant evolution and change. When our history commences in 1789, the first industrial revolution had not started in America (the first American factory was 1793). The policy-making structures and the core of our political culture pre-dated the “first” industrial revolution.

American S&L Ed has been a policy area entrusted to serve the interests of states and localities as they operate within a national capitalist economy–and a global economic reality. P&P, MED and CD, have been adjusted and modified to deal with these two hard realities: an ever-changing capitalism and global economic order, and the inefficiencies, inequalities and externalities befalling our home communities and jurisdictions. American ED has accordingly bifurcated to address competing demands placed upon it.

Progressives see capitalism’s glass as less than half-full, and task themselves to correct for its inequalities, injustices, and externalities–and while they vary on whether or not to work within, or replace, capitalism, their core instinct is to empower individuals (“people”) to defend themselves against its deficiencies. This is a traditional defining characteristic of community development. The community as a whole is the basic reference point for economic growth and a benchmark for CD programmatic goals. CD’s tension with individualism, profit, greed, and negative effects of various Mainstream ED strategies, programs and tools is evident throughout our history.

What is missing, and has been missing from most of the CD history, is where economic growth fits in. The principal goal of MED. S&L ED historically, rightfully or wrongly, has set economic growth as a prime core goal. Economic development (MED) “copes/manages” with low or no-growth, but it does not “seek” it. Progressives previous to 1965 or so, accepted and even desired economic growth and used its programs and strategies to promote “assimilation” or “integration” into it. Accordingly, thru most of our S&L history, P&P has been economic growth-oriented.

Until the end of WWII, most Progressives were content to work within, and support, albeit with social reform programs, a sustainable capitalist system. Jane Addams and Saul Alinsky, for example, fought to ensure immigrants/ethnics, workers and a neighborhood right to participate effectively within a capitalist economic order. Progressivism’s support for capitalism broke down dramatically during the Transition Era–and will be dealt with in later modules. Suffice it to say, the breakdown in the definition of acceptable and sustainable economic growth has widened considerably the chasm between MED and CD, and is no small factor in polarization and politicization characteristic of our Contemporary Era.

In contrast to this, Privatism and Mainstream ED (MED) advantages the risk-taking individual or firm which is the economy’s agent for innovation, economic growth and personal prosperity. Generally “advantage” involves limiting government. So government non-involvement enters this picture, if only to delegate ED policy to the individual (private sector or even the corporation itself) or to conduct the ED policy itself. MED prizes public-private partnerships. Cost minimization (in its various forms, low taxes for example) is the best way to assist a growing firm, and regulation should be minimal, used only when necessary and effective. More on this in later MED modules.

Mainstream ED tasks its strategies, tools and programs to maximize capitalist and firm growth, while ensuring that excesses, such as over-concentration of its economic base by one sector, is counterbalanced by diversification or retention. MED is highly sensitized to market competition, and S&L MED jealousy preserves the vitality of its own “community”, the economic base of its particular geographic area against intrusion by other competing economic bases. These days that competition is global; in the old days it was regional and then national.

Privatists not only accept capitalism, but sincerely believe it is the best system, like democracy, to promote growth, prosperity, and individual happiness. Instead of valuing community as a whole, Privatists value risk-taking, achievement, and the proceeds of which (both positive and negative) accrue to the individual. Continuing my maritime metaphor, they believe capitalism’s “rising tide lifts all boats”, to the general laughter of Progressives who observe some boats are tightly “chained” to their anchors and accordingly sink when tides rise.

Progressives distrust the profit motive, are very sensitive to the appearance of “conflicts of interest”, and often assume Privatists inherently pursue self-interest and any public-private EDO tends to “corruption”. The reader might pick up at this point that public-private hybrid EDOs cross over a fault line. Somehow, this fault line disappears when such a public-private CDO, like a foundation or think tank (Policy World) espouses the correct view or writes a check. Whatever! Public-private hybrids are a central topic of this history, and privately-governed EDOs (chambers, for example) are an integral and vital element in American ED. Progressives are way more comfortable with government EDOs, and nonprofits.

Political Culture and ED Policy-making

Political culture is the foundation (some argue the cellar) of a community’s policy system and the bottom-rung of its policy-making process. Political culture is internal to each individual state, and each individual jurisdiction-community policy system. Each community/state policy system will include both cultures (at least theoretically) and each culture comes in several flavors, that is neither P or P is monolithic, both exist on a continuum. Governance and policy structures often required compromise–and that is why, ultimately, each of our fifty states has its own somewhat unique policy system–and why Charleston South Carolina is not Boston or even Houston–which is certainly not Los Angeles or Tulsa.

ED-related state and local policy systems are quite complex; that complexity creates a great deal of variation among states in and of itself. Consider what occurs as we move up the geographic hierarchy. There are many neighborhoods in a city/towns, many cities and towns in a county, and many counties in a state. A lower-level policy system becomes a sub-system of a superior or higher-level policy system. When one thinks about this interwoven complexity of S&L policy systems, it is no big deal, but it does ground oneself on the realities of what an economic developer must confront every day and alerts us to the variation that is natural to our policy landscape. That hyper-variation is at odds with much of our policy-related literature–and our strategies and programs.

When the reader thinks about political culture, she should recognize that (1) its core elements consist of values, personal preferences derived from experience, socialization, and beliefs that often defy science and “rationality”–emotion intrudes into a political culture; (2) differences in each of these elements create choices between policy alternatives that necessitates a decision (or non-decision) on which to implement; (3) and the policy-making process is a more-or-less agreed-upon way to make these choices and render a legitimate decision.

A policy system can be” open”, i.e. a goodly number of individuals and policy actors can meaningfully participate in policy-making, or “closed”, where relatively few individuals and policy actors make the decisions. My history asserts ED policy-making systems are usually more closed than open–relatively few individuals and actors participate meaningfully. That last sentence is important to the ED-relevant political culture. MED seems naturally to be more closed than CD, but to read the CD literature one cannot escape the ever-present fear of excluding those for whom one seeks to empower. There are many reasons for American S&L ED/CD’s more closed policy systems, but to feel that tension think about holding a “public meeting” to explain a policy initiative, or tax abatement. Have you ever taken the local school superintendent out to dinner? Let’s not even mention unions.

P&P are not mass-based political cultures. Most of the citizens/members, taxpayers and residents of a jurisdictional-community policy system, for many reasons, do not become involved in ED decision-making. The occasional public hearing, perhaps, but not consistently over time. In fact ED planning, at its best, attempts to expand this participation. But truth be told boards of directors, mayors/city councils, and governors/state legislators make most of the decisions in plain sight with handfuls of folk in attendance–usually entities/individuals directly affected.

Rather our policy processes are crowded with opinion-leaders, activists (often community developers), constituents, bureaucrats, Policy World experts, media, winners and losers affected by the policy, and those who use the policy to accomplish non-ED purposes. Elected officials for example, saturate the ED policy processes. I once conducted a series of public hearings for a nearly $400 million (1990’s dollar) controversial professional hockey stadium receiving tax abatement; not one average citizen or resident showed up. There were probably fifty or so who fit the descriptions in the first sentence.

As Two Ships history reflects those who regularly participate in ED policy decision-making. P&P draws from an elite-based culture, with high education, wealth, and status that dominate the inside policy processes of day-to-day ED policy-making. Business elites, political elites, neighborhood activists, and economic/community developers, including Policy World, have been dominant participants in ED policy-making for over two hundred years. In the 20th century, unions, later universities snuck in, but normally (ignoring NYC) they don’t hold a candle to the Big 3. I will strongly argue that whether or not it is Privatism or Progressivism, the more wealthy one is, or the community’s largest employer is one heck of a powerful player in ED/CD policy-making.

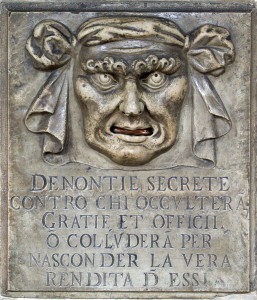

Secret denunciations against anyone who will conceal favors and services or will collude to hide the true revenue from them. Doge’s Palace in Venice, Italy

The power of elite-based political culture is not so great that it predetermines choices. Ironically, consensus in a closed policy system can be overwhelming. Elites, normally fractured, opportunistic, and have multiple conflicting interests, usually find a way to work within this closed system. So political culture does not “cause” or compel certain policy decisions. If one could measure these elite-based political cultures, it is not likely that they highly correlate with policy outputs. ED decisions are either shoe-ins or highly contentious and result from choices made while the sausage grinder of each policy system’s processes their involvement. Where rationality, an adopted plan’s goals, and professional expertise fit in, is anyone’s guess. While some may think I am talking about government policy processes, they should sit in on a chamber board of directors meeting.

How to Distinguish Between Privatist and Progressive-leaning Policy Processes

The two cultures infuse their values, beliefs, concerns and priorities into their policy-making decisions/outcomes, and they are reflected in strategies, tools, and programs adopted. Several key structural and policy distinctions important to S&L ED have ebbed and flowed throughout the 200+ year history. For example:

- Economic/community development should be led by, and conducted through, (1) private-sector leadership and public-private EDOs or (2) government and government-directed EDOs (nonprofits).

- economic development should directly benefit private firms so that hard-working, risk-taking individuals can acquire wealth from which the community as a whole can prosper and grow; or (2) economic development that directly benefits the community, not the private sector, preferring instead to benefit people, principally thru non-profit and community-based organizations

- Privatists accepte that the community competes against other communities for wealth, status, and economic growth in the national and global competitive hierarchy—without growth community decline is inevitable; or (2) Progressives decry the “mobility of capital” and task themselves to empower economically/politically disadvantaged residents unable to effectively compete because of inequalities that follow from the highly competitive national and global competitive hierarchies

A Privatist is wary of government being the primary agent of social and economic change. Limited government is preferred and business elites are invited to participate in the making and implementation of economic development policy. Private leadership is preferable to government/politicians in economic development; limited government preferable to activist, redistributive government. To a Privatist, prosperity and economic growth are best achieved by a dynamic private sector which creates wealth and opportunities for citizens and residents. The community will prosper through individual hard work, innovation, risk-taking and entrepreneurship. The community benefits from providing a supportive infrastructure and low-cost environment to private enterprise. These are tenets of MED.

For a Privatist, inequality provides motivation for individuals to participate more fully in the economic sphere. The community should level the playing field for firms so they can compete with firms in other communities, or create a supportive risk-taking environment (often characterized as low taxes, a willing and cheap labor force, and less regulation). In this perspective government can partner with business or business can direct economic development to the benefit of the private sector and the community. As business competes with other private firms, the community competes with other communities for limited resources, population/workforce, innovation, wealth-creation, and economic growth—failure to compete leads to stagnation, decline and in the worst case, a community “death”.

Progressive communities, conversely, see the jurisdiction, not only as their place of residence, but as polis, in which citizens working together benefit individually/collectively, achieve individual meaning and economic prosperity–together. “It takes a village” taps this conception that individuals achieve personal empowerment by inclusion in a caring community-polis. If each element of a community “does her thing” well and provides benefits to community, members of the community will prosper and provide meaning and support to its members. Business is a member of the community and its actions and decisions must reflect community interests and values.

Raising the capacity/prosperity of the least advantaged may be the ultimate purpose behind Progressive economic development. Progressivist economic development confronts inequality resulting from residents unable to effectively participate in community prosperity/governance. A requirement imposed on Progressive economic development is that it must empower the least advantaged. That requirement is also expected of private sector and firms. Progressives see the private sector less as an engine of growth and innovation, than as society’s vehicle for distributing the benefits of growth and prosperity to community members. There is mistrust of the profit motive, propelled as it is by greed, and is often perceived at cross purposes with community economic development goals.

Don’t expect any “Welcome to our Privatist (Progressive) community” sign when you cross a state, municipal, or county boundary. How are we to know? Privatist and Progressive communities are very different. An economic or community developer would be hard put not to feel it from the get-go.