Module 7: Unions in CD

There was little that smacked of religious fervor that characterized private unions as semi-political movements. In the Early Republic they first appeared as manifestations of a newly developing economic class: what Marx would call the proletariat, the working class of Early American industrialism. In the earliest decades they were for the most part “native”, i.e. not foreign-born, artisans working in the first industrial and commercial firms of early Republic Big Cities.

As Walters described it, “As early as the 1820’s, an assortment of artisans, visionaries, politicians, and opportunists put together a series of organizations to help workers. They stand at the opposite extreme from Protestant missionary [our second wing] activities. The two kinds of endeavor shared virtually no personnel, drew leadership from different classes, and disagreed over the effectiveness of religion as a means of social change”[i]. These embryonic CDOs were not accepting or comfortable with the tender mercies of early industrial capitalism.

Early Republic Origins

The proto-union Third Wing CDOs arose from nativist artisan/worker (the two were hard to separate) concerns prompted by separation of residence from workplace, and small-batch, transition from hand-crafted to mass-machine manufacturing production that organically and incrementally occurred in the first several decades of the Early Republic’s rising Big Cities. In a past module the reader discovered one such Third Wing grouping, the Middling Interest, and learned of its critical role in Josiah Quincy’s adjustment of the Brahmin Elect (Wing) to Early Republic urban mass politics–and his construction of a new charismatic strong mayor policy system. The Middling Interest included these folk, our tradesmen and truckmen.

Called “workingmen’s associations, by the mid-1820, there were literally hundreds of such “local labor societies”—organized around the workplace, not place of residence. Workforce was taking on amore modern composition. For the most part they were “journeymen”, or skilled workers and, in fact this was the initial appearance of craft unionism.

In the 1820’s they are not composed on ethnic immigrants, but mostly “native English Protestant Americans”; immigration, however, would pick up steam during the 1840’s—Tammany Hall conducted its first immigrant recruitment program in 1841. Like guilds before them, workingmen associations hoped to set production rules and standards, and a benefit/recruitment package that provided a basic floor of practices, rights and benefits for their “craft” and particular workplace. In the 1820’s their chief demand was to establish a ten-hour, not sunrise to sunset, working day. They also had other important political (anti-draft into state militia, eligibility to vote) and economic (debtor prisons) as well.

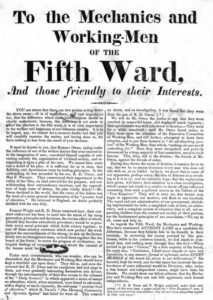

Philadelphia, in 1827, the nation’s second largest city, population totaled a wee less than 100,000 (Pittsburgh was only 7,000+), generated the spark that mobilized workingman associations in all the hegemony’s Big Cities. There, a journeyman’s carpenter’s association (600 workers) went out on strike, for the ten-hour day. The strike quickly collapsed, but the reaction from other workingmen associations proved transformative. The not-always-obvious need to join together to press one’s demand took hold; in 1828 a citywide federation of workingman’s groups was formed: the Mechanics Union of Trade Associations, composed of 15 workingman’s associations.

The Mechanics Union, believing it needed an action arm to accomplish its objectives, formed in 1829 the Philadelphia Workingman’s Party. The Party agenda included free public education, end of imprisonment for debt, ending compulsory militia service—and eliminating local restrictions on sale of liquor (temperance was now a social reform movement). They stridently opposed “corporation charters” (the dominant Early Republic MED EDO and will be subject of several future modules), because the delegation of public powers and tax abatement, in their mind, only made the rich, richer (Walters, p. 185).

The Workingman’s Party spread to other cities. Wikipedia claims (from I know not where) sixty cities formed a workingman’s party between 1829 and 1832. Walter’s states “it appeared throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and New England—winning “impressive” victories in Newark, New London and Wilmington—and came close in NYC. IA workingman’s association convention in 1832 Boston resulted created the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics, and Other Working Men.

Workingman Parties were mostly unsuccessful. Philadelphia’s collapsed after two years in 1831, and after a Philadelphia 1836 6,000 strong workingman strike, they failed nationally—effectively ending the 19th century union third party movement. The failure to sustain a labor-based, socialist political party, the path Europe took, meant that in America unions became relegated to “interest group” status. That unions were interest groups advocating programs and policies to political parties cannot be denied—but they were always more than political advocacy.

Historically, unions injected values closely identified with CD into private workforce management and operations. They were “people-focused” (their membership), often very involved in MED and CD policy-making processes, and have consistently checked the practice of MED in municipal and state policy systems a century before most textbooks admit. While As Two Ships sadly does not dwell on unionism’s impact on MED, it does discuss key movements in several cities that significantly affected the course of MED history. A place has to be found for unions, and the Third Wing seems the most logical in that unions have been consistently linked to many CD neighborhood (and city-wide) as well as “mobilization” EDOs and strategies. Today unions, public especially, are very involved in urban politics and major players in CD/MED policy processes.

In any case, the Workingman’s Party Movement refugees transferred allegiances to both Jacksonian Democrats and (Republican) Whigs after their demise. Perhaps surprisingly, those alliances worked wonders. In an atmosphere of desperation created by the long-lasting 1837 Panic, state legislatures adopted not only the ten-hour day—indeed President Martin van Buren in 1840 by executive order required it on federal contracts (Walters, p. 188)–but successfully produced legislation “reforming” corporation charters and ended imprisonment for debt. An 1842 Massachusetts Supreme Court decision (Commonwealth v. Hunt) began the legal process to legitimize workers organizing to form a union and achieve demands through collective bargaining.

Over the remaining decades, unions increased membership and assumed greater importance in the workplace, the corporation, and in the community ED policy-making process. That unions, private and public, have played disproportionately in CD, Alinsky for example, then Chavez, and since 1970 too many to name, suggests the MED approach is usually “one-bridge-too-far” for unions. Tax abatement and corporate welfare, the cry from the 1829 Philadelphia Workingman’s Party, is still heard loud and clear. Their role in the Textile War was included in As Two Ships. Minimum Wage and Right-to-Work are major Contemporary Era battlegrounds. This short case example is my best sense of when unions made their first meaningful appearance in American ED–and my succinct explanation of how they entered into S&L ED policy systems and processes.

Footnote

[i] Ronald Walters, American Reformers 1815-1860, consulting editor Eric Foner (Hill and Wang, New York, 1978), p.180.

[ii] M. Christine Boyer, Dreaming the Rational City: the Myth of American City Planning (MIT Press, 1994), pp. 44-5.