Theme 2: Module 9

Off to Urban Competitive Rivalries and Transportation Races Pre-1840 State-Chartered Corporations and Canals

Henry Clay embraced the strategy as a key element of his American System platform. So in 1825 Congress approved several canal-related bills (Rivers and Harbors Act, General Survey Act). Included in the former legislation was a funding authorization to the Corp of Engineers which was entrusted with a significant role in “internal improvements”. From that point forward, federal involvement in canals and other infrastructure was possible. Federal involvement, however, was always quite controversial.

Previous to Jackson (who hated federal involvement and regarded infrastructure as a purely state affair) there had been several presidential vetoes of federal involvement in various internal improvements. The Supreme Court’s Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) decision, however, paved the way for federal involvement in interstate commerce—and legitimized a possible national role in state and local internal improvements. That activist federal government, paying the way to state and local infrastructure, was not to be. Not if Andrew Jackson had any say in the matter–and he did, certainly after 1828.

So as explained in the previous module, states and local government had to take the lead in installing developmental transportation infrastructure to connect the city-building urban dots scattered across the American continent. They utilized the state-chartered corporation as their principal Janus-External EDO, and by and large the developmental infrastructure got built. This module is an outline of that.

Things did not end well–at least for the states. After the Panic of 1837 (which lasted well into the 1840’s), a reaction against the state-chartered developmental transportation corporation resulted. The reaction came in the form of a series of referendum which amended state constitutions to insert clauses which restricted and regulated our earlier described public-private partnership. That story will be presented in the second half of this module.

First ….

Off to the Competitive Urban Hierarchy Races: Canals and Railroads

Massachusetts Railroads

Philadelphia and Baltimore

State-Corporation Charters as Engines of Technology Innovation and Venture Capital

Early transportation infrastructure (roads) meant access into a city’s hinterland—hinterlands were the source of domestic migrants, raw materials and agricultural products to process and export domestically and internationally. By the 1810’s or so the combination of domestic migration, immigration and transportation innovation facilitated significant city-building in the nation’s interior.

New cities grew rapidly, presenting both opportunity—and rivals for control of the hinterland in between. Distances were greater, as were trade volumes; waterborne transportation couldn’t satisfy demand. Railroads could–but the technology available was literally laughable given the vast distance and incredibly difficult topography. Success in canal-building (Erie Canal) resulted in herd of states and Big Cities to rush to building canals and roads to access them. Counter-intuitively, that success also inspired a novel (1820’s), horrifically expensive transportation innovation: the steam locomotive.

This image is part of the collection of historic photographs of Baltimore County, Maryland owned by the Baltimore County Public Library, Towson Maryland USA. http://www.bcplonline.org/

The race to break into the Erie Canal’s lock on Ohio’s Midwest grain and corn markets was when the Erie Canal opened for business in 1825-6. Pennsylvania State committed to fund its public/private, canal/railroad alternative, and Ohio approved an 1837 (Ohio) Loan Law creating a state program to loan one-third of canal or railroad expenditures to private entrepreneurs. Some large cities did not compete at all (Charleston SC). Where canals were not commercially feasible–they froze in winter and simply were useless in crossing mountains–some other technology had to be devised if the Big City was to compete in opening up the nation’s interior. Baltimore was a interesting case in point. If it wanted to challenge Pennsylvania in opening Ohio, it had to cross over the Appalachians. So he City and its private sector “innovated”.

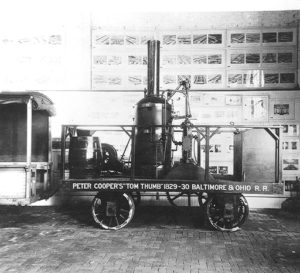

Baltimore, the nation’s third largest city at the time, committed to an unproven and horribly expensive mode, the railroad. Inventor/investor, Peter Cooper (former real estate developer of Baltimore’s Canton neighborhood) and twenty-five local business investors led by Charles Carroll (signer of the Declaration of Independence) raised venture capital (VC) to finance design and installation of track, railroad stations, and a new technology (the steam locomotive) to compete in the race to Ohio. They had no track nor locomotive, just a hope and a prayer–and community support.

The investment group (1827) issued a 42,000 share “subscription” (a low-priced stock offering) to the Baltimore community. Like today’s crowd-sourcing, hundreds of Baltimore residents bought a share or two in a railroad with no assets or locomotive–$3mm (1827 dollars)–a substantial sum–to lay track between Baltimore and Ellicott City.

With the track installed (1830), investors proposed a late summer race between a horse/stagecoach and Cooper’s new-fangled invention, the “Tom Thumb” locomotive–America’s first steam-powered locomotive. The hope was the race would motivate investors into a second VC round to finance Tom Thumb, “the engine that could” power the Baltimore & Ohio and open up Ohio’s isolated agricultural production to eastern markets.

The race was held.

Tom Thumb broke down, almost immediately.

The horse literally trotted to victory.

and VC flowed into the RAILROAD project.

Doesn’t technological failure crush VC? Let’s ask Elon Musk. In Baltimore’s case, the 1830 race triggered a City of Baltimore buy-in. In return for board seats, the City injected $3m equity (proceeds from tax-exempt municipal bonds) into the private company, reorganized into a hybrid quasi-public city commission. Empowered to issue tax-exempt bonds and conduct eminent domain/tax abatement, that city commission/private corporation laid the track, built local stations and developed a working locomotive, complete with patents. B&O built the first passenger station and profit-making steam locomotive, and was the first to enter Ohio (1852). B&O won the competition with Pennsylvania. B&O went on to become today’s CSX.

Elon Musk

The more things change, the more things stay the same!

Nearly 200 years later, innovation and VC still reflect hope, not actual performance. While Tesla’s Elon Musk got off to a better start, his Tom Thumb electric car already “worked” (selling for $100,000 with somebody else’s battery). Yet, despite no profits in sight, Musk’s “Tom Thumb”-equivalent electric car drowned in private/federal/municipal/state VC–like the 1830 B&O. More germane to state-chartered corporations is Musk’s SPACE X corporation which has entered into partnership with NASA (and others) to pave the way for interplanetary travel (colonization of Mars) and commercial development of space. Like B&O when it started, the technology did (does) not exist, and SPACE X, and its government and private partners had to experiment and develop it. The Tom Thumb-like failures are well-known to the reader. Yet, in its way, SPACE X is a 21st Century Silicon Valley opportunity for economic developers–and the nexus that firm/government partnership has already generated from its LA suburban HQ in Hawthorne CA, to Texas, Florida, Virginia, Washington DC, and Seattle.

Tom Thumb provides a glimpse into our three hundred-plus year economic development history, a history that includes public VC for privately-owned technology innovation–not to mention crowd-sourcing. In Baltimore’s city commission one sees an early version of our quasi-public development authority, and a government VC EDO. What’s more this was not new in 1830. State equity capital to private firms began in the colonial period. Tom Thumb and the B&O were only one example of literally hundreds.

Baltimore’s commission was not the first public/private railroad EDO, that being in 1817 New Jersey.

Footnotes

[i]Carter Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890 (Columbia University Press, 1960), reprinted by Greenwood Press, Westport CT, 1974, p. 268.

[ii] Peter Bernstein, Wedding of the Waters: Making of a Great Nation (NY, W. W. Norton &n Co, 2006).

[iii] https://www.canals.ny.gov/history/history.html

[iv] Carter Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890 (Columbia University Press, 1960), reprinted by Greenwood Press, Westport CT, 1974, p. 10.

[v] “Lottery” compares to general public investing in public debt such as a bond. Using lotteries a significant portion of public infrastructure were financed, not through taxes, but citizen “investment”. The general public willingly purchased these infrastructure bonds.

[vi] Bruchey’s overview of 1790-1860 Pennsylvania’s charter issuance reveals total of 2,333 business charters/special acts were approved: 64% were transportation, 11% insurance, 8% manufacturing, 7% banking, 3% gas, 3% water, and 4% miscellaneous.

[vii] George Washington (1784) was an investor-owner of the Patowmack Company which attempted to connect the Potomac with western territories. The company went bankrupt. The early canals were short, and constructed in the South. The Great Dismal Swamp Canal (Virginia/North Carolina) opened in 1805 (Washington was involved with it as well) is allegedly America’s oldest presently-operating canal—it later become the starting point for the Inter-coastal Waterways Canal (Reynolds, Waking Giant, op. cit. p. 15).

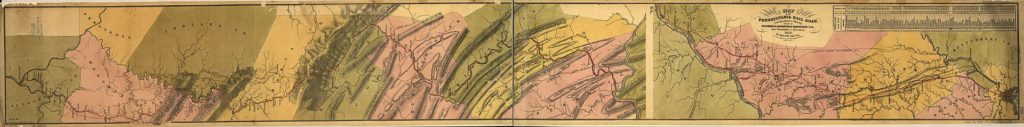

The Erie Canal engendered considerable apprehension in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. The Erie Canal stole the Ohio hinterland from them and further was destined to capture agricultural production of the northern Great Lakes areas. Philadelphia, the nation’s second largest city in 1830, felt further threatened by rival Baltimore (3rd largest city with only 200 fewer residents).

Fearing Baltimore would establish a trade route into southern Ohio, Philadelphia, believing it held the advantage of better Ohio access through Pittsburgh, decided that a mixed canal and railroad system–the Pennsylvania Mainline) to Pittsburgh. The State of Pennsylvania issued bonds, not municipalities. Believing rail too risky, the state which was funding the infrastructure thought canals would be cost effective and easier to build. The multi-modal system compelled numerous break-bulk transshipment points. Canals also froze in the winter when the grain shipped. Erie Canal handled more traffic and hauled heavier cargoes. Pennsylvania spent nearly $100 million dollars on its Main Line canal/railroad system—a project directed by a private-chartered corporation. (Bruchey, 1968, p. 132). It was completed much earlier than B&O but was non-competitive with the canal and then the railroad.

Baltimore on the other hand dependent on local investor institutions since the State declined to participate, instead authorizing Baltimore City “to purchase up to 5,000 shares in the company …. The City used property tax revenues to finance the railroad. (Dilworth, 2011, p. 153). Railroad construction, impeded by constant legal harassment by hostile neighboring states that placed legal barriers on Maryland-owned infrastructure that crossed state lines, pinned its hopes on the steam powered railroad. They put their money into the startup “Baltimore and Ohio Railroad of Baltimore City” (1827), believing/hoping it could conquer the intervening mountains. (Angel Jr., 1977, pp. 111-16). When the Erie Canal opened, the race was on.

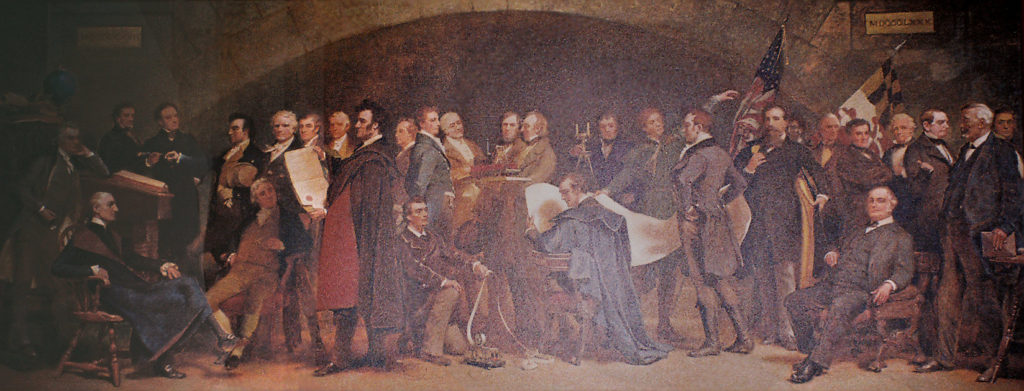

Founders of B&O at 1827 Incorporation Meeting–Seated left of front center is Samuel Morse of telegraph fame

B&O laid track across Maryland while experimenting with new locomotives. In 1830, the famous little engine that could, the “Tom Thumb”, ran a test run. In 1837 the B&O crossed the Potomac at Harper’s Ferry Virginia. By that time the city of Baltimore had established a commission to work with the railroad, and in 1836 the city purchased $3 million dollars of B&O stock and another $1 million in the related Baltimore & Susquehanna Railroad. Because neither Pennsylvania nor Virginia wanted Baltimore to succeed, roadblocks were placed in B&O’s path. B&O did not reach Wheeling until 1853—twenty five years after construction had started. Post-Civil War acquisitions in which B&O acquired key Ohio rail lines ultimately provided backdoor access into Pittsburgh itself, putting a stake thru Pennsylvania’s hybrid Mainline—in the 1880’s! The race lasted for over a half-century.

The Erie Canal dramatically demonstrated to other cities that they “could conquer the barriers that limited their development through a strategy which promised tremendous potential for commercial growth … [that] large sums of money could be easily raised for public works by utilizing state credit …. When states shared interests in economic development similar to those of cities, the state could promote programs to aid urban development through sale of state bonds”. (Kantor, 1988, p. 49).

Other New York canals followed in short order: Oswego, Chenango, Cayuga-Seneca, the Champlain, and Delaware and Hudson. Ohio constructed two major canals: between Cleveland and Portsmouth (the Ohio River) and Cincinnati and Toledo. Virginia, Indiana, New Jersey, Maryland, Illinois also completed important canals. Canals, it seems, were another example of the infamous herd-like, copycat imitation that repeatedly characterizes diffusion of economic development tools and strategies throughout our history (Goodrich, Canals and American Economic Development, 1961).

Massachusetts Railroads

After 1840 Cities, not States Drove the Competition and Ran the Races

Goodrich estimates the pre-Civil War face value of state government state-chartered internal improvement corporations was in excess of $300,000,000 and that of local governments about $125,000.000[i]. These should be regarded as huge sums relative to current valuations. They reflect, however, that pre-Civil War state-chartered corporations financed canals. Railroads ran earlier, of course, only in the 1840’s did they “gather steam”. City ED strategies drove railroad developmental infrastructure–particularly after states, adopting state constitutional gift and loan clauses took themselves out of the railroad infrastructure financing game–leaving it to their urban “creatures”, the cities. That complex story will be told, o mirabile dictu, later in the module.

State approval, however, masked who really led the drive for state charters: municipalities. Louis Hartz (Hartz, 1948) observed that “state investment at its height was of minor significance compared with investments by cities and counties”. Henry Pierce (Pierce, 1953) stated that 315 municipalities “pledged approximately $37,000,000 toward the construction of (New York’s) roads between 1827 and 1875”. Primm’s study of Missouri in the 1850’s (Primm, 1954) asserted cities and counties along the railroad routes bought most of the stocks of the state-assisted railroads—i.e. the state issued the bonds and the cities and counties bought them.

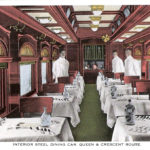

Railroad competition was hyperbolic compared to that engendered by canals. Cities needed railroads and would do almost anything to acquire or improve railroad access. An example of rather extreme municipal involvement is Cincinnati’s 1869-73 ownership and operation of a railroad to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Authorized by the state legislature, the municipal-owned railroad was an “effort to shore up the city’s economic decline relative to faster-growing cities such as St. Louis, and Chicago. (Dilworth, 2011, p. 258) Suffice it to say, every major, and not so major, city of the period buried in its scandal closet an outlandish railroad dependency story. If a city did not connect to other cities, its future was obvious.

Milton Heath (Heath, 1948) reported cities and counties financed $45 million railroad bonds in the pre-bellum south. Bruchey concluded Baltimore, Cincinnati and Milwaukee subscribed to stock, purchased railroad bonds, or guaranteed the indentures of railroad companies. In some instances, he asserts outright grants were made (Bruchey, 1968, p. 135). Why?

City development and prosperity were tied to important transportation improvements that permitted easier, faster, and cheaper commercial penetration of the sprawling new nation …. Transportation innovations and …commercializing the city hinterland could spell the difference between stagnation and prosperity …. With the introduction of each transportation breakthrough, cities and the political leaders faced the prospect of fierce competition with other cities, old and new, to win economic domination over their regions … political decisions could not help but be influenced by the rise of regional rivalries for economic growth. (Kantor, 1988, p. 40)

State-chartered corporations were used for both, and by the 1840’s canals were decidedly secondary. Railroads (the private railroad corporation, as in transcontinental railroads) for the next half-century became the dominant, external-MED EDO. We will send considerable time in our future article on “Western ED before 1900) on the railroad’s role in the West (and in the South as well), but it was railroads that opened up the western Midwest, with 1850’s Illinois and 1870-90 Minnesota being the pioneers—and to whom a great deal of contemporary MED attraction and promotion programs, tools and even sub-strategies were first developed and used. (For example, in 1873 a railroad corporation renamed Edwinton, North Dakota to take advantage of attracting German immigrants to settle there—the railroad branded as it “German” by renaming it Bismarck North Dakota).

External MED developmental transportation strategies receded to a less dominant position after the completion of the transcontinental railroads and the “drive to the Pacific”. Their last, incredibly amazing success was in the late 1880’s when railroads opened up an obscure city, with no ostensible reason to grow. Today known as Los Angeles. It was jump started—and nearly ruined—by railroad corporations. But in between, external, “connect-the-dots” MED revolved around city-building and developmental transportation strategies, tools and project initiatives.

Footnotes

[i] Gunn’s argument, while drawn from New York State, was meant to apply to other states.

[ii] Michigan defaulted because the majority of its defaulted debt was caused by Morris Bank’s transportation loans were refinanced to British investors who later forced Morris into bankruptcy.

[i] “Lottery” compares to general public investing in public debt such as a bond. Using lotteries a significant portion of public infrastructure were financed, not through taxes, but citizen “investment”. The general public willingly purchased these infrastructure bonds.

[ii] Bruchey’s overview of 1790-1860 Pennsylvania’s charter issuance reveals total of 2,333 business charters/special acts were approved: 64% were transportation, 11% insurance, 8% manufacturing, 7% banking, 3% gas, 3% water, and 4% miscellaneous.

[iii] George Washington (1784) was an investor-owner of the Patowmack Company which attempted to connect the Potomac with western territories. The company went bankrupt. The early canals were short, and constructed in the South. The Great Dismal Swamp Canal (Virginia/North Carolina) opened in 1805 (Washington was involved with it as well) is allegedly America’s oldest presently-operating canal—it later become the starting point for the Inter-coastal Waterways Canal (Reynolds, Waking Giant, op. cit. p. 15).

[iv] “Lottery” compares to general public investing in public debt such as a bond. Using lotteries a significant portion of public infrastructure were financed, not through taxes, but citizen “investment”. The general public willingly purchased these infrastructure bonds.

[v] Bruchey’s overview of 1790-1860 Pennsylvania’s charter issuance reveals total of 2,333 business charters/special acts were approved: 64% were transportation, 11% insurance, 8% manufacturing, 7% banking, 3% gas, 3% water, and 4% miscellaneous.

[vi] George Washington (1784) was an investor-owner of the Patowmack Company which attempted to connect the Potomac with western territories. The company went bankrupt. The early canals were short, and constructed in the South. The Great Dismal Swamp Canal (Virginia/North Carolina) opened in 1805 (Washington was involved with it as well) is allegedly America’s oldest presently-operating canal—it later become the starting point for the Inter-coastal Waterways Canal (Reynolds, Waking Giant, op. cit. p. 15).