Theme 2: Module 10

The 1837-44 Panic, Gift/Loan Clauses, and Say Hello to Railroads

The Stained Legacy

The DTIS paradigm dominated MED through the 1860’s. As we shall see DTIS permeated both External and Inward MED, but in this module series we concentrate on External MED–connect-the-urban dots developmental infrastructure. At the outset I confess to the reader this series in its hap-hazard way leads the reader into a sometimes tiresome, always repetitive story line that involves the principal EDO that carried out both Inward and External DTIS: the state-chartered corporation. The state-chartered corporation, not the Chamber, is our first major and critically important EDO. The Chamber, for those of you who a reeling on the floor, at least its modern form is a post-Civil War EDO, which will of all things eventually lead the fight against the last External MED version of the state-chartered corporation, the publicly-empowered railroad corporation. That battle against the railroad corporation, and a previous post-1837 negative reaction to External DTIS combined to leave a seriously negative legacy that pervades our American S&L ED to the present day. In other words, External MED’s DTIS strategy, first paradigm and all, is very controversial today. The bottom line issue–with both External MED DTIS and the state-chartered corporation–is that the strategy inherently forces a choice on whether MED is a government-driven strategy or a public-private capitalist strategy. In the Early Republic, the powers-that-be (to be described in these Themes and Modules) preferred, and with only a few exceptions, relied on public-private-partnerships that was the core of a state-chartered corporation. It was an organizational vehicle that permitted both government and the private sector to join together in a shared public/private project.

In short, DTIS acquired a negative, scandalous historical legacy that continues to this day. That legacy, as we shall see infused an emerging community development approach to economic development, and provided to it legitimization, and “fuel” to grow. It also mobilized a populist movement that sometimes overlapped with community development, but otherwise permeated the hard-pressed farmer and rural populations in the South and West–in the Midwest, with German and Scandinavian immigrants, it took yet another turn. In essence, the reader should sense that this history suggests 19th Century DTIS, the EDOs employed, and the consequences of significantly affected the course of American politics and policy systems, and in its way fostered a second, if not a third (populist), approach to American Economic Development.

To better understand its nature and whether the polarization it generated was warranted in all instances, this module outlines its use for turnpikes/roads, river/canals and steamboats. Given the inherent limitations of each transportation mode in the first and second phases, I argue the state-chartered corporation was successful in achieving its object: connecting the urban dots. The reader should be aware there is a literature which does not agree with that point of view. The nub of their argument is that the debt accumulated by states and municipalities during the period under discussion, mainly for canals–railroads were too new–defaulted during the Panic of 1837. The onus for the Panic-induced state defaults usually centered on the state-charted corporation and its use in building canals, and debt generated by the DTIS strategy. The reaction against state default and the abuses alleged caused by the state-chartered corporation created in effect a nation-wide series of constitutional amendments (today every state has one version of these still on the books) that defined in one way or another how public and private sectors can work together (or not) on a joint project. The common name given to these constitutional clauses, and subsequent legislation and judicial decisions that ensued, are “gift and loan clauses”. That public-private relationships and interactions are central to MED these gift and loan clauses have profoundly affected and even directed the course of our American S&L history–and continue, as amended over time, to do so.

To me, the start or beginning of this negative legacy is unfair (mostly), certainly inaccurate, and that DTIS and state-chartered corporations–always vulnerable as “developmental”–were often victimized and used as a scapegoat for deficiencies of the state legislature and a policy process created by a land rush/settlement boom which often accompanied the DTIS strategy. It was not the canal debt, nor the deficiencies of the state -chartered corporation that forced state defaults. Just the opposite, in most cases (not all, of course) canals had been constructed for the better part of forty years previous, and given their inherent limitations had achieved their object-goal. As to debt, much of it had already been retired. The real culprit in 1837 was railroads and defective state legislatures–plus the bad timing of the default itself. In 1837 the railroad was fairly new, the gazelle industry of the 1840’s, its public debt profile was embryonic. The Panic interrupted railroad projects which had just commenced, many still in the midst of construction. The reality that railroad debt was often held by foreign lenders, not domestic, also played a role in a state’s willingness to choose default over raising taxes–the more logical, if politically incorrect, response to inadequate revenues. In any case state chartered corporations, public debt, and state defaults put a stain on canals especially, and the early, Early Republic DTIS strategy that seemingly continues to this day.

As to the state-chartered corporation, that EDO was our first primary EDO. It is part of our heritage, but it too should be viewed as transitional. Born in the Articles of Confederation it was entrusted by the developing Federalist Party as the cornerstone of its public-private approach to banking, DTIS, and the jump-starting of fundamental industrial capitalist infrastructure (manufacturing, insurance, for example). It inherited a view/ethos of private-public, and of commercial and landed elites that established a closed ED policy-making process which, as we shall, see led to a succession of rebellions, movements, and President Andrew Jackson. One might be forgiven for wondering if today this has repeated itself with the rise of post-Soviet Union global capitalism/NGOs, the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the decline of America and the rise of China–in many ways the opposite environment confronted during the Early Republic.

Not without its deficiencies, the state-chartered corporation was synonymous with early, Early Republic DTIS also incorporated the deficiencies of its public partner (usually the state legislature). Highly controversial, the state-chartered corporation itself, with its style of private-public partnership fostered a national/cultural polarization and help generate a partisan two-party policy system which continued through the Civil War. The state-chartered EDO became a prime focus of a counter-movement with the arrival of Jackson in national and state/local politics, and the post Panic of 1837 Gift and Loan clause “movement” that followed defined and restricted the types/level of government of public-private partnerships each state would allow. This first phase of gift and loan clauses (there would be another after 1873) effectively thrust the financial burden of DTIS on local governments and policy systems. That counter reaction occurred just as the third DTIS phase gathered momentum, and it was instrumental in the increased use of the (transcontinental) railroad in which the state, while still incorporating railroads by state charters, reduced its role in direct financing to the EDO itself. The railroad, replaced the “Articles of Confederation/Federalist” state-chartered corporation, with a railroad-corporation EDO which was more autonomous of government, verging almost to state capitalist EDO prototype similar in several ways to the late 19th Century Czarist Russia (and its trans-Siberian transcontinental railroad).

But state gift and loan clauses redefined the public-private nexus, diluted and weakened the state’s willingness to assume leadership in DTIS, and by intent or by default left the DTIS implementation mostly to local/municipal level governments. That they were ill-suited to the immensity of this task will be left to other modules. The reaction to DTIS and the new transcontinental railroad demonstrated the latter had created a power imbalance between the public partner/business/farmer client and the continental railroad led to its own polarization–and eventually to the Populist and Progressive political movements. That will be considered in a later module, but the legacy which began in the course of events detailed in this module presumably started off this chain of events.

Gift and Loan Clauses: Regulating the Public/Private Partnership

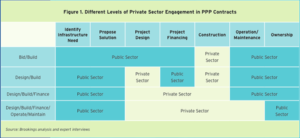

The state-chartered corporation was our first hybrid, public-private EDO. True to its bifurcated nature, an hybrid EDO (HEDO) contains built-in tensions, potentially conflicting goals, and accordingly, needs sustained oversight and a stress on accountability. While HEDOs can be found in both community development and mainstream ED, HEDOs in MED have arguably received more than their fair share of accountability.

An HEDO that bridges public and private almost always crosses over the “Progressive-Privatist fault line. For those uncomfortable with capitalism itself, the inherent drive for profits, greed if one wills, of its entrepreneurs and the finance capital (today’s neo-liberals) which towers over them, the power inherent in an HEDO is a genuine fear, in desperate need of restraint and checks. Legitimate concern with the effects and consequences of concentration, the likelihood that inequality is in varying manners fundamental to capitalism, leads to distrust. In an atmosphere such as induced by the horrific Panic of 1837–which we repeat lasted until mid-1840–the state-chartered corporation came under attack. The HEBO became a Bosch-like “Garden of Hellish Delights” potentially, if not actually, practicing every evil and corruption known to mankind. In many ways the state-chartered corporation because a legislative and legal scapegoat. The attack that followed, expressed in a myriad of state constitutional clauses, legislation, and subsequent judicial interpretations, left a legal and structural impression on public-private partnerships that persisted well into the 1950’s.

Legislation, judicial precedents, and state constitutional clauses are one thing. There is no denying that upon hindsight, the state-chartered corporation was unstable and deeply flawed. It should not have been allowed to continue much longer–despite its obvious success in building canals. Two other consequences of the reaction against state-chartered corporations, however, merit comment.

First, there was corruption, but one also discovers negligence caused by inexperience, opportunism, and simple incompetence of both individuals and institutions. There are important lessons to be learned from the sad chapter in our history, and the mythology that has followed has inhibited our learning them.

Secondly, our reaction to the faults of our initial HEDO can be likened as jumping from the frying pan into the fire. We quickly, very quickly, latched onto a second HEDO the railroad corporation (and later utilities, and even resource extractors). From the 1840s into the 1890’s–and after for that matter–we suffered from the mixed bag of delights produced by the railroad corporation. They too were repudiated in the end.

Before we begin our tale of 1837 and the Gift/Loan Clauses, it is worth retelling a story about our favorite Early Republic economic developer, George Washington. Washington was, as previously told, a land speculator–assembler. He also was a noted, and quite diligent early canal builder. He was a founder in the Great Dismal and a major (presidential) backer of the Georgetown (DC) canal. Knowing Washington’s interest in canal-building, the Virginia legislature granted in 1884 to Washington, then a private citizen (during the Articles of Confederation), 150 shares of the (state-chartered corporation) James River and Potomac canal companies “in return for his services to the state and [his dedication] to the cause of canal-building” (Wood, 2006, p. 44).

This gift threw Washington into a total dither—should he accept them or not? As Wood describes Washington’s reaction, it is clear the decision was a very serious matter, critical to his personal integrity, called at the time “appropriateness”, it references the “appearance” of conflict of interest. Accordingly, Washington widely sought reaction and advice. Personally, he deeply believed in canal-building, not only to make money, but also to unify the nation by making travel and commerce easier. But he also believed to accept the shares would seem a public gift—a gift which compromised his most treasured asset, his “disinterestedness” (no conflict of interest).

“Few decisions in Washington’s career caused more distress than this one”. Thomas Jefferson convinced him to decline the shares “, donating” them “instead–twelve years later while he was President–to the college that eventually became Washington and Lee” (Wood, 2006, pp. 44-5).

Despite their awkwardness by today’s standards, these infrastructure-related municipal/state hybrid public/private organizations were genuine economic development vehicles, essential to legitimate urban public purposes. That the structure itself was clumsy and inherently faulty is also accurate. Such is hindsight. But, corporate charters did raise necessary capital, house the expertise, and build, manage, and operate the intended project—and that was needed at the time.

As Robert Lively observed, A persistent theme in the nation’s economic development has been:

the incorrigible willingness of American public officials to seek the public good through private negotiations … its obverse: the equally incorrigible insistence of private citizens that government encourage or entirely provides those services and utilities either too costly or too risky to attract unaided private capital [is also true]. It was especially on the undeveloped frontiers of the nation that capital needs and development needs conjoined most pressingly. Social overhead capital, especially in transport, was a frontier need and a prerequisite for economic development. (Lively, 1955)

That persistent dichotomy–the need to combine public and private to achieve necessary change and modernization while venturing into a powerful and volatile alliance that puts aside public and private as a necessary check to each other–has followed HEDOs to the present day. It has resulted in multiple “bypass” judicial precedents and tortuous-awkward legislation that has confused and weakened key MED/CD strategies and programs. That is the heritage that follows from the tale below.

The Panic of 1837

The Panic began in 1837. Economic growth did not resume until 1842—making the Panic one of the longest in our economic history. Before it was over eight states (Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, and Pennsylvania—and one territory, Florida) defaulted. Four states repudiated at least some of their debt (Arkansas, Florida, Michigan and Minnesota) (Wallis, September 2004). America had one of its worst binges of state bankruptcies—a public debt crisis of the first magnitude.

The alleged principal cause of these state defaults usually centers on state/local debt associated with our infamous canal and railroad infrastructure-related corporation charters. Scandals associated with bankruptcies of charter infrastructure corporations, their inside “crony politics’ captured the media, and public’s attention. They were the problem that had to be fixed—and state legislatures and state referendums fixed it by inserting gift and loan clauses into their state constitutions.

While not every state defaulted, after the Panic nearly every state over the following decades amended their state constitutions to insert some form(s) of a “gift and loan” clause that limited the use of state funds for private corporations and individuals. As new states entered the Union these statutes were included in their initial constitutions so that by the turn of the twentieth century all states (Tarr, 1998, pp. 110-13), had incorporated a form of gift and loan clause into their state constitutions. What was in 1840 a regional concern, had generated into a national solution.

Yet as we shall discover, the clauses did little to stop public financing of private transportation infrastructure. If this was the proper measure of gift and loan clause success, then they failed. They certainly changed its “form” (HEDO), however. The old-style corporate charter was left behind—in its place was new forms of public financing channeled to a new purely private organization: the modern corporation which first appeared in 1850’s: railroads (Chandler Jr., 1977). That shift will prove to be one of the two or three most critical 19th themes developed in this history.

Rather than halting state or local investment in private transportation corporations, gift and loan clauses simply resulted in such assistance being provided in different forms and in different levels of government. Gone was the corporate charter. In its post-1850 place was the railroad corporation. Consider what happened after the first wave of gift and loan clauses. From 1866 to 1873 “state legislatures approved over eight hundred proposals to grant local aid to railroad companies. New York, Illinois, and Missouri together authorized over $70 million worth of aid” (Tarr, 1998, p. 114).

A second wave of gift and loan clauses would follow. It also did not materially affect state/ local involvement with railroads (and mining) corporations either. Such subsidies remained characteristic of Western and Mountain state economic development into the mid-twentieth century.

American cities and states continued to struggle and experiment to find a suitable, effective and accountable structure or rules (conflict of interest, lobbying, etc.) that regulated this most critical of economic development relationships. We will again pick up this topic in Theme 3.

“Blame” for Failure of the Corporate Charter

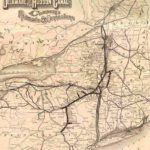

NY’s Delaware & Hudson: State-Chartered in 1823 as a Canal Company, it Became a Railroad still in operation

The causes behind each state’s debt crisis and state reaction to the crisis vary. One wonders if corporate charters, or more precisely public financial relationships with state-chartered corporations were as much scapegoat as causal factor in the state fiscal crisis.

First, there was a huge regional variation regarding what “caused” the default crisis. The South’s debt crisis concerned defaulted plantation land sales by inadequately capitalized state-chartered banks (see a future module). The Mid-Atlantic/Midwest was closely linked to railroad infrastructure—but not canal which had been retired successfully by the 1840’s (Wallis, September 2004, p. 7). As to the Midwest, most of Michigan, Minnesota, Indiana and Illinois defaulted debt resulted from post-1836 “loans” (Wallis, September 2004, p. 34 Table 3) for transportation infrastructure and an expectation that future property tax receipts from future homestead land sales[ii] generated by the infrastructure would pay off the debt. That story will be told in the next module.

Secondly, States themselves were complicit in the bankruptcies by incurring debt repayment obligations and failing to earmark revenues to pay for them—or—by identifying revenues that proved insufficient (especially in a Panic) to pay off troubled debt. In both cases politics, legislative inexperience, incompetence and exuberance were also causal factors. Yes, there was corruption, but it was not pervasive.

Thirdly, reforms (gift and loan clauses/statutes) differed among states regarding the types of financial activities allowed or rejected, and the level of government reformed, mostly states (local was left untouched). What we individual state reactions, became institutionalized nationally when future states inoculated themselves from this fiscal disease by adopting these state-level public-private restrictions, while continuing to offload the problem of infrastructure financing and urban competition to their localities. Public relationships with railroads substituted for the state-chartered corporation, after state-level gift and loan provisions were enacted–and the burden of financing/implementation mandated principally to the municipal level.

My core contention is that railroad charters were the problem in several older Big City states. In the heavily tracked Northeast, Maryland and Pennsylvania defaulted, but New York, Massachusetts and Ohio, each of which had earmarked tax receipts to pay off transportation debt, managed to avoid default (New York just barely) (Wallis, September 2004, pp. 8-11).

Pennsylvania, and to lesser degree Maryland had invested heavily in rail transportation corporations, but never raised or earmarked taxes, instead relying as a pay as you go approach. Both defaulted. Subsequent conventional interpretation of gift and loan clauses relies heavily on the Pennsylvania, Connecticut and New York cases. In these states gift and loan initiatives were directly linked to railroad-chartered transportation debt–but not canal debt. Most of that had been retired, or had not defaulted. Railroads, however, were new, were just starting in their “scaling up” and commercialization of innovative technologies, and were a different breed of entrepreneur than canal-builders. The timing of the Panic could be considered an “almost-perfect fiscal storm”. Today, it might be argued that investing in railroad state-chartered corporations was in the midst of a “bubble” that caught state legislatures in its raptures, like our turn of the 21st century Wall Street “dot-com” debacle.

Whatever the merits or failings of railroad-related corporate charters, the two states that defaulted made no adequate provision to counter-balance their financial liabilities. Pay-as- you go is inherently vulnerable to events that created large-scale fiscal distress such as Panics that reduced tax revenues–(keep in mind today’s retirement pension and health care debt; the problem has repeated itself). In essence, state debt for transportation-related corporate debt was made more risky by faulty legislative fiscal behavior.

Accordingly, Pennsylvania and other states that relied on current appropriations to pay debt obligations were among the most restrictive in terms of future public/private partnerships. From a subsequent Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision, the concept of “public purpose” emerges. If a state could not tax for that purpose than it could not issue a debt for it. Other states copied it—and it was later included in the federal 14th Amendment—but interpreted by the federal Supreme Court as subject to local determination. (Pinsky, January 1963, pp. 281-82)

The solution, reflected in subsequent gift and loan clauses, restricted the state from these relationships and debt instruments, but permitted counties and municipalities to enter into such corporate-related debt—provided it was approved by public referendum. These legislatures “freely authorized counties and municipalities to incur debt to aid railroad construction and these units did so eagerly”. (Pinsky, January 1963, p. 278) Galie reports in 1845 New York State state-corporation charter debt was about 20% of total debt, but perception of corruption as a motivating factor in railroad charter-related debt prompted gift and loan reform in its new 1846 constitution —such restrictions applying only to the state (Galie, 2012, pp. 211-15).

In the Midwest, the specific problem took a different turn. Indiana, for example, started funding its Mammoth canal system in 1836, following that with financing for railroads to connect the canals. Construction began in 1837 and the state cut current property taxes in anticipation that the new infrastructure would generate more taxes. When the Panic hit, they impacted newly-sold bond issuances while railroad and canal construction was still in process–there were no revenues or generated taxes at that point. That revenue deficiency need not have been fatal, but states were reluctant to increase taxes to compensate for revenue deficiencies. Ohio raised taxes—and avoided default–and then there was Illinois.

In their “reform” many Midwestern states, chose to remove themselves from funding local transportation projects, but left municipalities free to pursue them with municipal resources as did New York.

Types of Gift and Loan Clauses and Sub-State ED Systems

The most common gift and loan clause (the “credit” clause) precluded “the credit of the state shall not in any manner be given or loaned to or in aid of any individual, association or corporation” (Pinsky, January 1963, p. 228). This reform prevented the most common forms of state/corporate debt–and affected the most common MED strategies and programs. The “reform” that resulted from imposed restrictions on “credit of the state” require our understanding of how the past state bond issuances were translated into state-chartered corporation financing.

Pre-reform when the State issued the bond, it transferred/donated it directly to the state-chartered corporation; who then sold the state bond, and kept the proceeds. The first reform entailed issuance of a state bond which was then “swapped” or exchanged for railroad corporation stock which was still regarded by both legislature and courts as a permissible form of joint venture. To ensure that such swaps were illegal, a second gift/loan clause was necessary (a “stock” clause). Neither of these two clauses precluded loans, gifts of land, or grants financed directly from current appropriation. If one wanted to extend this closure to loans, land donations, and grants meant a third clause (current appropriations clause) had to be approved. Not all affected states adopted the three reforms.

The problem for economic developers is variation among states in the choice of which combination of gift and loan clauses to employ, led to current day variation in our individual state ED-relevant legal requirements—and the EDOs affected by them. “As the twig is bent” suggests these 1840 decisions, incorporated into state constitutions, interpreted by subsequent judicial decisions, and incorporated into future legislation led to individualistic state ED requirements regulating who and what private/public arrangements are suitable and specifically as to how key MED strategies and programs would be structured, defined, and empowered.

From the “mélange” of nineteenth century state gift and loan clauses, an important element of economic development, its core tools and structures which related to public/private relationships, would be reshaped to reflect whatever each state incorporated into their gift and loan clauses. This is an important explanation why we currently have fifty “different” state economic development systems.

Future states upon including these clauses into new state constitutions varied considerably in adopting the first, second or third–or mixtures. That ensured significant variation in public-private HEDOs, and substantial variation in MED strategies (loans, eminent domain, tax-exempt bond-issuance) and tools–a variation that constitutes a principal reason for the present-day reality of a fifty-state decentralized system of American ED.

At the turn of the century, some form of public aid limitation had been incorporated into the constitutions of a large majority of states. … Although the public aid limitations took certain common forms, the pattern which has emerged throughout the country is not uniform. The constitutional movement of the nineteenth century was an extremely pragmatic one; each change in each state was a direct reaction to the specific evils which had manifested themselves in that and perhaps neighboring jurisdictions. Some constitutions, therefore, contain only a credit clause, others join to it a stock clause, and still others have all three. The potential for diversity is further intensified by the fact that any or all of these restrictions may apply only to the state, to counties, to cities and towns, or to a specified combination of these. (Pinsky, January 1963, p. 280)

At its core, the gift and loan clauses restored the Winthrop-Puritan distinction between public and private sectors. The “credit” clause which was predominant in all regions reflected a shared belief that no longer should state legislatures consider private corporations as “public”, as potentially public instrumentalities [that could be entrusted with a public purpose], but should instead regard them as private and profit-seeking—with all the risks that speculative ventures entailed. That “shift in definition and attitude) marked the effective end of corporate charters as a hybrid EDO. Never formally declared illegal, they moved over in favor of the new transportation technological-commercial gazelle; the railroad corporation.