Theme 2: Module

Illinois Central Railroad and the Birth of the MED Attraction Strategy

So according to conventional wisdom, the era of state-chartered corporations was over sometime in the late 1840’s. It wasn’t–at least in Illinois.

As Governor, Jeremiah Morrow’s shovel, alongside DeWitt Clinton, threw the first dirt from the Canal

In the previous module one can sense the arrival of the railroad into the world of state-chartered corporations and internal improvements. Canals were important to the first crop of new Big Cities fed by the Yankee Diaspora. Cleveland, for example. Incorporated as a village in 1814; it was home to 1,000 residents in 1830. The construction of the Ohio & Erie Canal which opened in 1834 connected Cleveland to Great Lakes, the Ohio River (steamboat), and thereby easy access to the Erie Canal terminus, Buffalo. In 1836, incorporated as a city, Cleveland grew to 6,100 by 1840, and 17,000 by 1850. The midwestern regional hierarchy was slowly taking shape. Canal internal improvements made it possible.

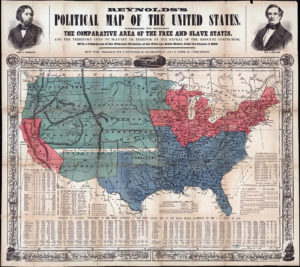

Canals were dominant in the 1837 Illinois Act. But politicians’ fear of railroad encroachment from other states, however, was very real. One senses that by the late 1840’s railroads had already won the battle and were emerging as the next transportation wave. In 1840 there were only twenty-four railroad miles under track in Illinois; by 1850 that increased to 111 miles–not exactly a transportation revolution. But in 1860, however, Illinois had laid almost 2800 miles of railroad track. (Clifford Thies, Development of the American Railroad Network, 2001, Table 3).

That does constitute a transportation revolution. Sam Bass Warner claimed in 1840 there were 3000 miles of canals and 3000 miles of railroads in operation in 1840. By 1854, one could travel exclusively by rail from NYC to Chicago or St. Louis (Warner, the Urban Wilderness, p.68). In hindsight it is apparent the Panic of 1837–and recovery after 1843 marketed a turning point in America’s transportation infrastructure. The breakout was during the 1850’s–and 1860’s.

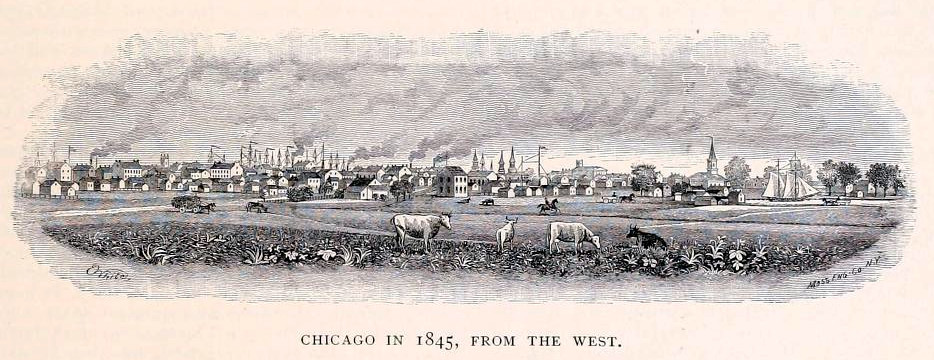

For the most part, the 1840’s were a lost decade for Illinois–with one explosive exception: Chicago. Chicago was the principal beneficiary of the 1830’s internal improvement acts. The sixty-one mile 1836 Michigan and Illinois Canal opened up Chicago’s agricultural hinterland. Only in 1848 did Chicago achieve railroad access when the Galena & Chicago RR opened up. In 1840, Chicago was the U.S. ninety-second largest city (pop about 4000), but by 1850, it was ninth (almost 30,000). An incorporated city in 1837; in 1848, the Chicago Board of Exchange was founded. Chicago was on its way by 1850–but it’s principal link to the outside world was by Great Lakes steamship from Buffalo and the Erie Canal. That was going to change in 1850 because of something called the federal land grant state-chartered railroad corporation–specifically, the Illinois Central RR, the nation’s first.

As expensive as canals were, the railroad–if only because of the distances and topography–were incredibly costly–and in 1853 there were only five commercially operative in the nation. Railroads were the seeming culmination of America’s developmental transportation infrastructure, and little-known at the time, the transformative gazelle that would industrialize the Big City states.

The earliest railroads were “short lines” that connected individual cities of size to canals or rivers; they were usually constructed in partnership with municipal governments and some state-involvement. That changed with the innovation of the federal land grant state-chartered corporation. I might add, so did External MED. External MED entered into a new “age”, the age of the railroad corporation as its primary EDO, and the “invention” of a modern MED attraction strategy.

The Land Grant State-Chartered Railroad–the Age of Railroad-led External MED

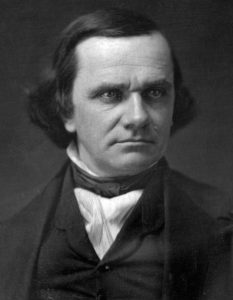

Thanks to U.S. Senator Douglas, our hero of 1837, a remarkable chapter in American S&L MED opened. Working with the state legislature Douglas “engineered” over several years a bill which, after approval, was signed by President Fillmore (1850). It authorized a federal land grant (intended for Illinois and several other states in on the deal) to create a new state-chartered railroad that in Illinois’s case would link Cairo to Galena (Illinois’ extreme south to extreme north) passing through Chicago.

On February 10th, 1851 the Illinois General Assembly approved the charter for the Illinois Central RR (ICRR), with support from Senator Douglas, and a certain A. Lincoln (who subsequently was retained as a ICRR lawyer). The ICRR became the first “land grant railroad in the United States”–it would not be the last.

Making a very long story, somewhat shorter (see Howard Gray Brownson, the History of the Illinois Central Railroad, 1886–reprinted in 2018), the story began with a canal chartered by Cairo’s City Council which secured in 1848 state legislation to be beneficiary to any future federal railroad-related land grant, than to a series of compromises with key adjoining states negotiated by Douglas, to a series of post-1851 Illinois state and federal legislation. The ICRR and the land-grant transcontinental railroad was no legislative accident.

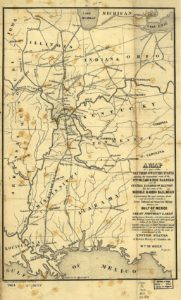

The ICRR, subsequently nicknamed “the Main-Line of Mid-America”, connected Chicago to the City of New Orleans (remember Arlo Guthrie’s iconic song detailing an ICRR train with that name), and eventually practically everywhere else in Mid-America. When it opened for business in 1856, it was alleged to be the world’s longest. Perhaps one might in a fit of exuberance call this the railroad that built Chicago–carrying Illinois, and Centralia IL, along with it.

Let’s be clear about what happened. A midwestern state has scratched together federal legislation and then empowered a state-corporation to become the nation’s largest railroad from donated federal land criss-crossing multiple states effectively operating from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico (a vertical transcontinental railroad)–linking most of Illinois by rail in the process. Illinois was opened up to settlement–homesteading, fostered, coordinated, and implemented, by the state-chartered ICRR.

American S&L External MED has entered into a new age in which the state-federal chartered railroad became the region’s principal External-MED’s EDO. The chartered-railroad corporation had become a genuine, conscious EDO actively, aggressively pursuing a “public-private” MED strategy–with ICRR the first of several–that extended almost to the end of the 19th century. Before it was over, ICRR alone had innovated a railroad-led city-building strategy that would open up the West, establish the foundational programs that today are standards in MED attraction of people and industry, and pioneer the first industrial parks.

A Lincoln Story You Might Enjoy

Tax abatement is sure to raise the blood pressure of most readers, so take your medication before you read this section. It involves our saintly Abraham Lincoln and his contribution to S&L tax abatement–and the ICRR. In January, 1856, Lincoln, as Illinois Central’s lawyer, argued before the Illinois Supreme Court that the Illinois Central Railroad didn’t have to pay taxes to McLean County. He argued the company’s state charter limited the payment of taxes solely to the State of Illinois. Lincoln won the case[ii]. Tax abatement is apple pie America. But there’s more.

Lincoln billed the railroad for his services ($2000); they refused to pay. Lincoln sent a new bill for $5000 that the railroad also refused to pay. So Lincoln sued the railroad. An appeals court granted Lincoln a $4800 judgment; still the railroad refused to pay. Lincoln sued to seize a locomotive engine and cars. The railroad paid Lincoln $4800. Lincoln deposited the proceeds into his 1858 Lincoln-Douglas Senate election fund. Ill-gotten tax abatement proceeds partially financed the election that launched Lincoln’s drive to be President.

The ICRR got its revenge, however. It made available to Senator Douglas, free of charge, a railroad car for him to travel on during his 1858 Senate campaign–which, of course, he eventually won (even though Lincoln won the popular vote, but lost in the Democrat-controlled Illinois Senate).

Involved in the ICRR decision, was a certain ICRR Vice-President (and Chief Engineer), George McClelland, recently retired from the U.S. Army and just back as an American military observer in the Crimean War. McClellan, shortly after, became President of an ICRR subsidiary, the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad. Lincoln, too got his revenge–he fired McClellan as Commander of the Army of the Potomac four years later. McClellan then ran against Lincoln as the Democratic Party’s 1864 presidential candidate–and lost. Eventually in 1868, McClellan was appointed as New York City’s first department-level economic development commissioner (the Department of Docks) in a deal between the New York City Chamber of Commerce and Boss Tweed. McClellan’s son worked with him in the Department, and eventually became Mayor of New York, whereupon he entered into his own ED adventures. Who said ED was a small world after all.

A Brief Glimpse into the External-MED Crystal Ball

This sorry experience did nothing to dissuade either Lincoln (as President) or Douglas (as Congressman and Senator) for proposing, voting for and securing approval of future internal improvements. Douglas was a confirmed railroad supporter. The latter opposed Jacksonian Democrat Presidents (Polk, Tyler and Pierce) who vetoed such projects. Chicago caught Douglas’s eye and after buying property there, he became its patron. The land grant legislation was part of his genuine commitment to Clay’s American System, his belief in the future of Chicago and the economic growth of Illinois–and a bit of profit tossed in. Douglas died early in 1861 from typhus, but in a little-known incident at Lincoln’s 1861 Inauguration Speech, Lincoln on reaching the podium had no place to put his stove-pipe hat. Douglas, right behind him on the platform, reached out and grabbed his hat, saying “If I can’t be President, at least I can hold his hat“.

Little-known as an economic developer, it arguably was central to his political career.

Lincoln, Homesteading and Transcontinental Railroads

Lincoln wasted little time as President, securing approval for the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 which authorized the development and construction of the 1912 mile transcontinental railroad built by three private companies created by federal legislation (Union Pacific, Central Pacific, and Western Pacific RR) over public lands, financed in considerable measure by U.S. (and state/local) bonds. Face value of the bonds was about $125 million. The railroad opened for business in May 1869.

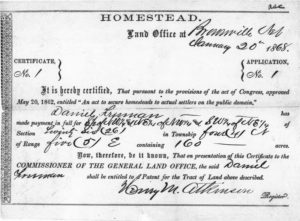

No taxes were levied during construction. Each company was paid $16,000 per mile built (then-current dollars) with bonus allocations for tunnels and mountains. Permanent land grants were made to the corporations, and a 400 ft. right of way was also included and additional acreage was awarded at stations” for subsequent commercial development to the benefit of the railroad. To ensure passenger traffic, but more importantly foster settlement, Homestead Act(s) were approved between 1861 and 1863. Three years after the transcontinental railway opened for business (1872), the Union Pacific went bankrupt, and the Credit Mobilier scandal erupted.

The geography of railroad competition expanded hugely with the Lincoln’s decision to open up the West with homesteading land grants. The Homestead Act and Transcontinental Railroad legislation[i] applied lessons learned from the 1850’s Illinois settlement managed through contract by the Illinois Central Railroad. In this manner ICRR put meat on the bones of ED attraction and recruitment for the next one hundred fifty years. It is from the ICRR that chambers copied their attraction campaigns; it is from the ICRR the South learned how to hijack northern firms and ironically to counter the South, northern and Midwestern cities copied the South.

To learn from the ICRR necessitates moving beyond the railroad’s “Darth Vader-like dark side”. Railroads were land-speculating monopolists that controlled prices, gouged homestead farmers which, in turn, triggered a semi-revolutionary Populist Movement that fractured American politics for more than a generation. Railroads held literally for ransom individual towns and cities, threatening to bypass their city unless sums of money were paid. Ward (Selling Places, 1998) cites that by 1875 300 municipalities in NEW YORK alone had paid sums to railroad companies to be included in their network. Cheyenne’s Board of Trade in 1870 paid $280,000 as did Denver, and a small city of 7,000 in California (Los Angeles) also paid a considerable sum (Ward, 1998, pp. 23-4). Eventually the Interstate Commerce Commission, a major Progressive reform, was established (1887) to deal with these railroad abuses. As far as the ICRR goes, in 1998 it was bought by the Canadian National Railroad.

To learn what we can about our history, however, we need to put these abuses momentarily aside and appreciate ICRR path-breaking ED innovation.

The Illinois External-MED Strategy Nexus

Illinois badly needed settlers. So the Illinois legislature authorized land grants for individual sale and contracted with the Illinois Central to structure/operate the program. (Ward, 1998, p. 11) Stripped to its essentials, state government delegated to the ICRR management of its people and business attraction strategy, provided it public powers to conduct a city-building economic development strategy as well.

ICRR launched an extensive advertising campaign across the Eastern states and Europe starting in 1854. Its tools included: mass promotional circulars, advertisements in major newspapers and trade journals, editorial support by newspapers, a promotional handbook, advertising on street cars, recruitment agents in immigrant entry areas, and agents distributed throughout Europe (especially in Canada, Scandinavia and Germany). “By the early 1860’s, the ICRR’s internal US campaigns … (promised) homes for the industrious in the garden state of the West.”

ICRR’s success spurred other neighboring states, Iowa in particular, to start their own people attraction efforts. ICRR also pioneered the art of “town site promotion”. It set up (apparently semi-illegally) specific town land development corporations (little EDOs) throughout Illinois; each attracted investors to fund infrastructure and costs for each town. Land was platted and sold in individual lots or bundles of lots. One ICRR land development corporation at its southern most terminus, Cairo, sold a bundle to a certain Charles Dickens, in an Ebenezer Scrooge moment (Ward, 1998, p. 21). Centralia Illinois, the spot where the two lines that constituted the original ICRR jointed, was named for ICRR in 1853–Michael Moore in his deindustrialization documentary, the Big One (1998) describes the closure of its primary employer, a candy manufacturer.

The ICRR model was in essence state government contracting with a private corporation to devise and manage its core economic development strategies. The railroad was given access to the necessary tools (land grants, tax abatement, eminent domain, public financing), and then left to its own devices. The railroad recruited through sophisticated promotional programs, city-building followed. Privatist to its core, the ICRR program achieved spectacular success in filling up the Illinois countryside. Its contribution to MED continued; at the turn of the century, the first industrial parks, created by a ICRR railroad in Chicago.

The Illinois Central Railroad and ED Attraction

To learn from the ICRR necessitates moving beyond the railroad’s activities. Railroads were land speculating monopolists that controlled prices, gouging homestead farmers which, in turn, triggered a semi-revolutionary Populist Movement that fractured American politics for more than a generation. Railroads held literally for ransom individual towns and cities, threatening to bypass their city unless sums of money were paid.

Ward cites that by 1875 300 municipalities in NEW YORK alone had paid sums to railroad companies to be included in their network. Cheyenne’s Board of Trade in 1870 paid $280,000 as did Denver, and a small city of 7,000 in California (Los Angeles) (Ward, 1998, pp. 23-4). Eventually the Interstate Commerce Commission, a major Progressive reform, was established (1887) to deal with these railroad abuses. To learn what we can about our history, however, we need to put these abuses momentarily aside and appreciate ICRR’s path-breaking ED innovation.

Illinois badly needed settlers. So the Illinois legislature authorized land grants for individual sale and contracted with the Illinois Central (ICRR) Railroad, to structure/operate the program. (Ward, 1998, p. 11) Stripped to its essentials, state government delegated to the ICRR management of its people and business attraction, and city-building economic development strategies. ICRR launched an extensive advertising campaign across the Eastern states and Europe starting in 1854. Its tools included: mass promotional circulars, advertisements in major newspapers and trade journals, editorial support by newspapers, a promotional handbook, advertising on street cars, recruitment agents in immigrant entry areas, and agents distributed throughout Europe (especially in Canada, Scandinavia and Germany). “By the early 1860’s, the ICRR’s internal US campaigns … (promised) homes for the industrious in the garden state of the West.”

ICRR’s success spurred other neighboring states, Iowa in particular, to start their own people attraction efforts. ICRR also pioneered the art of “town site promotion”. First, it set up (apparently semi-illegally) specific town land development corporations (little EDOs) throughout Illinois; each attracted investors to fund infrastructure and costs for each town. The land was platted and sold in individual lots or bundles of lots. One ICRR land development corporation at its southern most terminus, Cairo, sold a bundle to a certain Charles Dickens, in an Ebenezer Scrooge moment. (Ward, 1998, p. 21)

The ICRR model was in essence government contracting with a private corporation to devise and manage its core economic development strategies. The railroad was given access to the necessary tools (land grants, tax abatement, eminent domain, public financing), and then left to its own devices. The railroad recruited through sophisticated promotional programs, city-building followed. Privatist to its core, the ICRR program achieved spectacular success in filling up the Illinois countryside