The Cotton Belt was an overnight phenomena that took its own sweet time, over seventy years.

The development of the Deep South Cotton Belt, without any doubt, is the South’s S&L ED defining event. We cannot ignore the Cotton Belt economic base with accompanying social/political institutions established the foundation on which the South’s future ED rested. Not only does the Cotton Belt legacy affects the present-day South, but it is also essential to understanding our national S&L ED history.

Until WWII the reality created by the Deep South Cotton Belt contrasted with, and struggled against the reality unleashed in the textile mills/factories New England. The savage legacy of Civil War and contemporary racial polarization testify to critical role historical economics, cultures, and supporting political/policy institutions still exert on our daily lives in the 21st Century. ED, as always caught in the cross-hairs of those three dynamic forces, needs to better appreciate how and why it became a bi-polar handmaiden of opposing economic/political systems–if only to help prevent a future repetition.

In this module, the second in our four-module Cotton Belt mini-series, I describe the initial post-1790/pre-1816 “formation” of the Cotton Belt in Carolina’s and Georgia’s Piedmont geographies–focusing on its most salient geography–South Carolina’s Upcountry Piedmont. The post-1815 spill over of the Cotton Belt into the newly-acquired (through Indian removal or Louisiana Purchase) wilderness territories will be outlined in the next, third module, in this Cotton Belt mini-series.

How Piedmont South Became the Cotton Belt’s Womb

It all started, of course, with the (1794) cotton gin. It took a generation for that innovation to diffuse throughout the Piedmont geographies. The experimentation that followed, and more important to us the trial and error development of a new “fusion” Deep South political culture, overlapped with the establishment of a new agricultural economic base built around plantations, slavery, cotton and export. The culture (and politics/policy it produced) in its good time supported this new economic base produced its distinctive ED goals, strategies and programs, in stark contrast to that followed above the Mason-Dixon Line.

The term “womb” is a metaphor to describe where, how, and why the various dynamics of developing a cotton-plantation-export economic base produced a living embryonic Deep South policy system and culture destined to extent into other geographies once purchased or cleared of the Indians. The dynamics underlying Cotton/Black Belt growth/migration were introduced in the previous module. They include a revitalized plantation based on slavery, a “chronic migration syndrome” caused by soil depletion, the timing and execution of “Indian Removal”, the ebb and fall of cotton prices, tariffs, war, and economic Panics which triggered or depressed mass enthusiasm.

The Louisiana Purchase (1803) dramatically enlarged the potential geography for cotton expansion, and the inclusion of the mighty port of New Orleans (challenging Charleston’s previous dominance while prompting Mobile, and later Galveston’s ascendancy) would greatly motivate Charleston’s and South Carolina’s subsequent railroad-based ED strategy–detailed in our second Theme 3 mini-module series.

The Piedmont border regions, sparsely settled until the arrival of the Scots-Irish previous to the Revolution, attracted a hodge-podge of migrants, including post-Revolutionary War Tidewater emigres. Constrained by hostile Indian territories, pre-1800 life was hard (we call it hardscrabble) in these geographies–this was an early version of the American wild west. In thee desperate and opportunistic economies, the cotton gin was readily adopted and cotton planted to avoid bankruptcy, if not starvation.

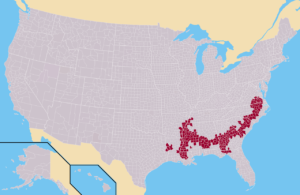

Geography played a major role in the formation of the Cotton Belt. Cotton didn’t grow in highlands or mountains, although it prospered in plateaus and valleys. Accordingly, e womb of the future cotton belt, centered in Piedmont, the highland “middle” of these three coastal states, immediately above and below the Fall Line. It is interesting to note development of key urban centers along the Fall Line–initially reliant on a trans-modal economic base (see-Map) and notice the present-day urban centers that grew because of transshipment opportunities/infrastructure investment required to connect the new Cotton Belt to ports.

With all this volatility, and the sheer number of “moving parts” required to set in motion the developing Cotton Belt , one can understand why the Cotton Belt developed in “bursts” rather than a steady expansion. Reading the history one realizes the Cotton Belt was formed through a series of land/slave booms (a real estate and slave-importation reminiscent of the future 1849 California gold rush) and ), that produced multiple irrational stampedes of entrepreneurial activity, land purchases, and town-building.

Settlement-building resulted, by necessity rather than planning. In any case these Cotton Belt urban centers were remarkably tiny–and incredibly isolated–by anyone’s standards, were almost simultaneous with statehood. Statehood approved during a state’s initial land boom meant that the political culture that got there first, drafted the state constitution–which almost immediately was rejected by soon-to-follow new cultural immigrants. It took a generation or more to meld the diverse political cultures into a more stable and coherent policy system (Alabama in particular, has yet to overcome its rocky inception). Deep South states and their policy systems were created previous to the their current political culture–which is not the way it is supposed to work, but that is a story which shall be told in later modules.

The South Carolina Upcountry Cotton Boom

The Fall Line middle areas of Georgia, South Carolina and southern North Carolina, our Cotton Belt womb, bordered not only on coastal Lowlands, but on the higher ranges of the Piedmont mountains. Called “Upcountry” [1], cotton plantations shared the landscape with predominant, Scots-Irish yeoman hardscrabble farming.

The Fall Line middle areas of Georgia, South Carolina and southern North Carolina, our Cotton Belt womb, bordered not only on coastal Lowlands, but on the higher ranges of the Piedmont mountains. Called “Upcountry” [1], cotton plantations shared the landscape with predominant, Scots-Irish yeoman hardscrabble farming.

At the close of the American Revolution (1783) the Upcountry was a backwater region, isolated from the main currents of South Carolina society which ran through the mercantile center of Charleston and the [Barbadian] plantation society of the coastal parishes [sometimes referred to as “lowlands”].

The interior … an untamed region which had experienced deadly Indian raids as late as 1763, supported only a coarse frontier society that was more frontier than society. In 1783 [Upcountry] was sparsely populated, almost exclusively white, and essentially unchurched … clustered in small settlements … on the fringe of the state’s export-oriented economy…. During the next half-century, this bare-bones backcountry developed … nourished by … cotton and evangelical Christianity [2].

Rice or tobacco did not suit Upcountry soils; and indigo, suffering from foreign competition, had expanded to the point it satisfied the limited market demand. Grain, which the Upcountry farmers sold to Lowcountry, was, by the late 1790’s, a glut on the Charleston markets. Lacking transportation access, the region was isolated, and economically adrift at the time of the cotton gin invention.

Upcountry soils, perhaps surprisingly, “proved as receptive to cotton as they had been forbidding to other staples“. In very short order, “The fertile Savannah River valley and other portions of the lower Piedmont quickly emerged as the heartland of the South’s first short-staple cotton boom” [3]. The early and easy success of cotton prompted the State of South Carolina in 1798 to pay the firm of Miller and Whitney (as in Eli), $50,000 to allow South Carolinians to copy their patent, and furnish two models for which would serve as an instruction kit. The year before (1797) Wade Hampton Sr., a Tidewater pioneering plantation owner to buy 3 gins which were the first to use water as a power source [4]. Georgia’s cotton gin monopoly was anything but long-lasting.

South Carolina, as a state, produced only 94,000 lbs. of cotton in 1793–most of which were long-staple West Indies cotton. By 1811 the South Carolina Upcountry alone exported more than 30 million lbs. of short-staple cotton [5]. This production velocity demonstrated the transformative power of the cotton-plantation-export nexus–and supports our description of the the Piedmont and South Carolina Upcountry as the “womb” of the future Cotton Belt.

Deep South Clash of Cultures: Origin of a Deference Culture

Perhaps the most nettlesome annoyance economic developers may have with my Chapter One model is that economic development strategy and programs are an output of a policy system. The tale related in this module is mostly how a distinctive Deep South policy system was formed. If the Deep South produced distinctive versions of strategy and program it is because the Deep South cotton-plantation-export nexus created its distinctive version of a policy system.

The Deep South culture while heavily influenced by Carolina’s Barbadian culture was a fusion of Scots-Irish and a modest Tidewater influence–and even some Yankee entrepreneurial input. In this section, I begin my description of two crucial element in that distinctive policy system: (a) the coalition between the noveau Deep South cotton plantation owner and the Yeoman/Scots-Irish; permitted by a unique utility of cotton as a cash crop that (b) lessening the underlying tension within the coalition and allowed the two cultures to develop a mutual deference by both groupings to the hopes/ends of the other. That mutual deference resulted in a volatile, constantly shifting policy system that frequently seesawed economic development policy, strategy and programs toward a southern “Whig-like” ED, and then in the opposite direction corresponding to Jackson’s well-known preference for state/local ED with little to no federal role, and a distinct resistance to state-chartered corporation and public-private partnerships.

At its most basic level, the antebellum Deep South political culture rested on the coalition and its mutual deference norms. The Civil War would end that, and the so-called “Redeemer” post-Civil War Deep South political culture had to be reforged, often unsuccessfully. Antebellum and Redeemer Deep South political cultures are not identical at all–they are fundamentally different.

At root, as we shall soon discover, the antebellum Deep South culture formed around the Scots-Irish antipathy to authority, and an instinctive tendency to view politics and policy as an elite-mass, zero sum exercise. Antebellum cotton plantation owners preferred to plant, harvest, and export cotton–and make enormous profits in so doing. They proved to be indifferent policy actors. Scots-Irish Yeoman farmers were another matter entirely. As shall be revealed in this and future modules, this wild swings they caused, were ameliorated a bit, through deference by antebellum plantation owners to Yeoman Scots-Irish perceptions and needs. The tension was lessened and the deference worked in the antebellum period due to the wealth creation produced by cotton. The Civil War changed that however.

Accordingly, as the reader proceeds onto the below-sections, she should be alerted I am interweaving two separate strands of thought: the first the Upcountry as the womb of the future Cotton Belt, but the second may be more critical to our ED history, the complex/subtle political culture that emerged in this period that with variation was carried into other states that became the Deep South Cotton Belt.

That culture accounts for much of (1) the state-level political culture that blended at least three major cultural influences into exceedingly subtle state policy system; and (2) the intensity and power of local, more homogeneous political culture that produced much of the support and resistance to MED strategy, internal improvements in particular. The remaining culture, needing integration into the coalition, the Barbadian–Charleston-lowlands based political culture, will be dealt with its own section below.

A New Generation of Plantation Owners

General Wade Hampton–The early years were truly a boom–bumper crops and high prices–for those cotton pioneers that successfully established major plantations. They made a fortune. Plantation owners such as Wade Hampton Sr. scion of the dynasty that included his son, Wade Jr., a famous Civil War cavalry general, and Reconstruction era governor. Virginia-born Hampton Sr., of Tidewater Royalist heritage similar to Washington, emigrated to the Upcountry before the Revolution. Among the first to switch to cotton (1797), by the time of his death (1835) Hampton Sr. had become the richest planter in America. It was Hampton that first imported the cotton gin to South Carolina. At death, he was reputed to be the South’s most wealthy planter.

Patrick Calhoun–Hampton’s Scots-Irish counterpart was Irish-born, Patrick Calhoun, also a Revolutionary War leader, and founder of a dynasty that included future Senators, and Andrew Jackson’s Vice-President (author of nullification and acknowledged leader of the antebellum South: John C. Calhoun). Patrick Calhoun’s descendants were major players in South Carolina politics through the entire 19th Century. Scots-Irish plantation owners such as Patrick Calhoun, were common, but they were the vanguard; most Scots-Irish remained on their hardscrabble farm.

Both Hampton and Calhoun, in any case, were typical, if exceptional, prototypes of a new generation of plantation owners , a noveau-riche made wealthy by the cotton-plantation-export nexus. Their sons and daughters will often follow similar lifestyles in similar policy systems–but usually in another Cotton-Belt state. In later sections when we describe antebellum policy-making the rank-in-file cotton plantation owner tended to follow the “lead” of these two charismatic plantation owners; they were major policy players in the early antebellum period–but as shall be seen, the typical antebellum plantation owner preferred to stick to his cotton. The key player in the antebellum Deep South was the Scots-Irish.

“Aspirational Cotton” and Deference Culture: Scots-Irish Yeoman’s Path to Heaven

The reader should discern my concept of “deference” is vastly different from conventional thought. Conventional thought asserts the Scots-Irish” masses defer to their betters, the plantation elites. My deference culture is two-sided, and mutual.

In that the plantation had replaced the feudal manor in Cotton Belt agriculture, the politics and relationships between these two sets of cultures collided, and colluded–and it was the former serf/freeholder Scots-Irish that were the more volatile. What divided and bonded them was that each possessed an shared “identity” that plantation owners were elite and the Scots-Irish were the “common people” (masses-yeoman farmers). Each knew his/her place–but the common people intensely wanted their share of of prosperity and wealth, and sharply resisted the elites getting more than their share. At the same time, however, more entrepreneurial yeoman farmers also wanted to create “in micro” a lifestyle and economic status that reduced the perceived inequality between the two groupings. Within the Scots-Irish lay an “aspirational” need to close the economic/elite gap: antebellum cotton allowed that to happen under the proper conditions.

This is a tension-filled cultural coalition that broke down on a regular basis–when cotton failed to produced wealth. ED frequently got caught in the cross-hairs. Since they could not escape each other in their isolated rural communities, each had to find a way to work things out if life was to be worth living.

Nevertheless, over a generation or two, an Upcountry coalition evolved and held together through a mutual deference relationship. When yeomen backs were “up”, plantation owners gave way to the masses, in policy-making, frequently retreating to their plantations and managing their affairs. The Scots-Irish would then dominate policy-making, usually in the state capitol, but planters held their own in the local hinterlands. Eventually good times would again roll, and cotton regained its wealth-creating magic. In those periods, yeoman Scots-Irish would settle down, and enjoy their good life, leaving policy to their economic betters. Deep South policy system politics had a discernible yin-yang tendency. To make this deference work, however, the yeoman demanded respect and consultation from the plantation elite. Yeomen also expected to profit from it.

Thus far the reader may see hints of today’s “populism” in this fragile policy system–but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Populism we must always remember is not linked to one ethnic grouping, but it can be linked to a shared state of mind and aspirations.

How Did this Deference-Based Coalition Work?

An unplanned consequence of the rise of cotton and the invention of the cotton gin, was that cotton economics offered to yeoman farmers what rice, wheat, and indigo could not; yeomen farmers could plant small amounts of cotton to generate income and satisfy status aspirations. Cotton was the perfect cash crop. You did not have to be a plantation owner to make money from cotton-raising. “Requiring no large capital outlays and subject to no particular economies of scale in production, short-staple cotton seemed the ideal cash crop for small farmers” [6].

With a purchase of a handful of slaves, yeoman farmers could quickly pay off their debt for slave purchase–and pocket the rest. They could purchase domestic slaves and mirror the plantation household. Any yeoman farmer could grow a field or two of cotton, send it to the plantation cotton gin, and it was like a second income, a gig economy within the larger cotton nexus. That extra cash made all the difference in hardscrabble farming, and created a shared bond between the “elite” and the “common people”.

This was no threat to the plantation owner. Just the opposite. When it worked it brought stability and civilization to their rural community. Cotton production as a secondary cash crop “incited industry among the lower classes of people, and fill the country with an independent yeomanry“, [allowing] “individuals who [previously] were depressed in poverty and sunk in idleness …[to rise] to wealth and respectability” which could be left to their progeny [7]. Like two porcupines making love, plantation owners “deferred” to yeoman, wary of their intense, if latent, hostility and its potential for sabotage and rebellion, and needing their support in a sea of black faces. The symbiotic relationship substituted a cultivated paternalism, not entirely dissimilar from the Roman patron-client/personalistic relationship. Moreover, Upcountry cotton plantation owner pioneers provided a role model, a can-do aspirational motivation, to hundreds of neighboring Scots-Irish yeoman hardscrabble farmers. .

Subject to Early Republic fluctuating cotton prices and partisan schism, yeoman farmers viewed their best hope for future advancement by making his hardscrabble farm a miniature plantation, and himself a small-scale plantation owner. Slavery, yeoman farmer ownership of a few slaves and use of cotton as a supplementary cash crop, produced a reasonable vibrant, if fragile, rural middle-class, and created an economic/political bond with plantation owners with whom they could ally for expertise, seed/resources and use of a cotton gin. Until the Civil War, when Sherman burnt the plantation and Reconstruction ended slavery, this morally reprehensible shared bond underlie the antebellum Deep South policy system.

That this required an extension of slavery to create a white agricultural middle-class is correct. Cross-class expansion of slavery was the core shared bond that sublimated the clash between the white cultures.

Expansion of Slavery

The “shared bond” between plantation owners and yeoman farmers dramatically increased slave populations in the Upcountry region–from 21,000 (1790) to 70,000 in 1810.

“In 1800 only 25% of all white families in the Upcountry belonged to the ranks of slaveholders. Yet by 1820 just under 40% … owned slaves” In the bordering lower Piedmont, the corresponding figures were 28% to 45%. [8]

The plantation owners owned more slaves by far. Indeed 35% of these owning slaves, owned fewer than two slaves [9]. Horribly when cotton spread beyond the South Carolina frontier into the wilderness after 1815, it kick-started the a large-scale nefarious “Second Passage to the Interior” of slaves from Tidewater to the depths of the emerging Cotton/Black Belt. Before it exhausted itself, this “middle passage” consumed over 1 million black slaves. Moreover, a slave-trader complex, series of slave auctions centers developed to accommodate this expansion–destroying what little existed of Black family life, and placing the most reprehensible features of slavery on steroids.

Maturity Arrives Quickly in “the Land of Cotton”.

Apparently “good times are quickly forgotten in the land of cotton”. The first Upcountry cotton boom was remarkably short–they all were, it seems. Upcountry Piedmont’s initial growth phase, however, shortened, was still remarkably impressive given the small number of Piedmont plantations, and the undeniable prosperity and production it generated is also testimony to aggregate small-scale production of yeoman farmers as well as plantation. From less than 100,000 pounds in 1793, by 1811 Upcountry produced over 30 million pounds. By 1802, the U.S. was Great Britain’s single most important supplier of cotton [10].

After a decade Piedmont’s first phase suffered from several serious jolts. As early as 1807, while the Upcountry was enjoying the last days of its U.S. cotton monopoly, the Napoleonic wars sent shivers into cotton prices. The War of 1812 shut off trade with Great Britain completely–although New England textile mills gradually replaced old England. cotton prices plummeted, and only after 1816-7 did they begin to climb back.

Volatility was cotton’s middle name. Cotton export and hence cotton prosperity was volatile from the start of the Cotton Belt. Cotton producers responded to price volatility by increasing the volume of cotton produced–depleting soils all the faster. The agricultural supply-demand dilemma also repressed consumer demand, prompting deflation that nailed debtors to the banker’s cross. That led to taking on more debt. The inability to pay spiraling debt off and the Panic of 1819 triggered cotton bankruptcies which officially ended the first cotton boom.

During all this tumult hard times set in–and cotton/soil depletion syndrome made its first appearance. Old (ten year old or so) fields declined and their productivity reduced. For awhile this was masked by simply adding new adjacent fields and expanding into new areas. Plantation owners when times got tough could sell and relocate to new areas. And primogeniture played into the migration picture as the first son inherited the plantation requiring other siblings to make their own fortune. Moreover, cotton price volatility exposed the fragility of Scots-Irish middle-class prosperity.

Migration solved any soil depletion concerns and after Jackson’s 1815 victory over the Creeks, plantation owner class led the parade into the wilderness of North Florida and Alabama (and Mississippi) especially. In a few short years–when cotton price recovered– they were joined by large numbers of Upcountry/Piedmont yeomen farmers and yeoman farmers always prone to migration for new opportunity, and second sons from Tidewater also poured into new areas from which Indians had recently been removed or pacified. The Alabama land boom that resulted was the most dramatic America had experienced to that point. That tale will be told in the fourth module of this Mini-Series.

Wrap Up and Segue Way

The sine qua non takeaway from this module is that cotton, export, agriculture and continuity with the late medieval era was the path into modernity chosen by the Deep South. The choice, simultaneous with the North’s adoption of manufacturing/industrial and finance capitalism, meant the two regions of the newly-established United States (our Early Republic) had selected remarkably opposite paths to follow. These radically divergent economic bases produced not only a Civil War, but paved the path for the emergence of a decentralized, region-based, state and local economic development–frustrating along the way an early attempt by the federal government to pay a meaningful role in state and local ED.

The Deep South’s cotton-agricultural-late medieval path evolved from the tri-state Piedmont geography and its structure and values reflected the cultural and economic consensus forged between two socio-economic-cultural groupings in the generation between 1790 and 1815. Innovation such as the cotton gin and seed experimentation, by no means restricted to either modern electronic/Internet-based technology, nor industrial capitalism, demonstrated that agriculture was not immune to its transformative dynamic. Nevertheless, it was in the Early Republic Era that the 5000 year-old Agricultural Revolution came to an end, with agriculture becoming a mere “sector” in an economy that was overwhelmingly industrial/finance capitalist. Late-medieval political/social/economic institutions, perspectives, and values accordingly had to cope and integrate into the “new world” that emerged. Distinctive and contrasting state and local policy systems were one consequence that we see evident today.

The United States during its Early Republic Era was consisted of two radically divergent economic bases–and cultural groupings. That its national government, increasingly unable to achieve compromise and consistent policy consensus, was unable to provide resources nor leadership to either modernization or economic growth. Unable to abate the almost inevitable disintegration of the consensus that had created the American constitution, the national government became little more than a regional struggle whose ultimate fate and direction could be settled only though Civil War–or acceptance of two independent nations. American state and local ED established its contemporary roots in this most troubled of Eras.

The cotton nexus (including plantation, slavery, cash crop and export) proved to be every bit the platform “crop” gazelle that textiles and the factory were in the North. That the former looked to the past, and would prove unable to compete with the “modern” meant that one region, the South, would be in for a rather rude awakening as time passed. That rude awakening, entrenched in its distinctive cultures, set the South “back”, and caused it to lag behind and become dominated by a northern Big City industrial hegemony–until a Second Reconstruction commenced in the mid-1930’s. That lag produced a major regional schism very evident in our history of state and local ED.

The Deep South cotton economic base exhibited its own profit life cycle–epitomized in the soil depletion syndrome and the serious deficiencies of slavery and the plantation. Migration and new startup plantation could mitigate these deficiencies only for so long. Upcountry cotton migration, in many ways an economic safety value, exerted profound economic aftereffects. Economic disruption ultimately caused by the Piedmont’s relatively undiversified economic base, creates yet another tale to be told in our Upcountry narrative. As the Cotton Belt moved inevitably west, the original womb of the Cotton Belt, the tri-state Piedmont evidenced economic and social decline that required the intervention of MED strategies and programs–and an overall strategy to diversify their economy. It will be no accident that after the Civil War, an industrial sector built around textiles mills will develop. That is a story for a later module in this Theme.

Footnotes

[1] The map provided in the module reflects the contemporary definition of Upcountry, but the reader is advised the historical definition of Upcountry is not identical to the abbreviated contemporary definition. In the Early Republic Upcountry was pretty much everything above and immediately below the “Fall Line”. Today its cotton heritage is lost, the region, dominated by I-85 corridor, includes ten counties. The Greenville-Spartanburg-Anderson CSA is the largest defined urban area. Clemson and Bob Jones University are its most well-known universities. Adrift in a sea of FDI, corporate HQs, and the South’s auto alley Upcountry is not what it used to be.

[2] Lacy K. Ford, Jr. Southern Radicalism: the South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860 (Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 5.

[3] Lacy K. Ford, Jr. Southern Radicalism, p. 7.

[4] David Duncan Wallace, South Carolina: a Short History (University of South Carolina Press, 1951), p. 364.

[5] Lacy K. Ford, Jr. Southern Radicalism, p. 7.

[6] Lacy K. Ford, Jr. Southern Radicalism, p. 7.

[7] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Southern Radicalism pp. 10-11.

[8] Sven Beckert, the Empire of Cotton, p. 103

[9] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Southern Radicalism p.12.

[10] Sven Beckert, the Empire of Cotton, p. Empire, 104.