Hard times hit the Upcountry especially because its soils were wearing thin. Upcountry plantation owners replaced lost fields by buying out bankrupted neighbors, but increasingly with acreage outside the Upcountry. Georgia and were natural beneficiaries. By the early 1830’s the good times were again rolling–until late 1837 that is when the Panic of 1837 set in and Upcountry returned to hard times once more, lasting into the very late 1840’s. Debt and soil depletion were again the main problems–and the cycle was repeated again. The Scots-Irish tendency to move on when hard times hit, now reappeared in earnest and each recovery from a downturn resulted in a cotton rush yet deeper into the Wilderness. Cotton was a migration machine.

When his own lands were exhausted, the typical Upcountry planter … ‘buys all he can from his neighbors … and continues the work of destruction [by inefficient soil management] until he has created a desert of old fields around him, and when he thinks he can do no better, sells his lands for what he can get … and marches off to a new country to recommense the same process [1].

So as Lacy Ford observed nearly half of the whites born in South Carolina after 1800 left the state, “proceeding in step-like fashion across the deep South“, first to Georgia and then a decade later moving on to Alabama. By 1850 more than 50,000 South Carolina-born lived in Georgia, 45,000 in Alabama, and 26,000 in Mississippi. In each of these states South Carolina emigres constituted at least 30% of in-migrants. Upcountry was the hardest hit–“a steady stream of upper Piedmont whites flowed into the [old] Southwest between 1830-1850, while during the same years whites abandoned the lower Piedmont for the cotton frontier in unprecedented numbers” [2]. On top of cotton problems, a “Corn Panic” ensued after 1845, driving still more farmers out. Boom and bust.

But there were silver linings in these clouds. The interesting dynamic that resulted from this substantial migratory shift was that Upcountry lost its economic losers, who departed for other regions already growing explosively from the cotton boom migration. A steady stream of cotton entrepreneurs, having for various reasons lost their Upcountry fields, moved on to other new regions of the explosively developing cotton empire. Ironically, that cheap and available wilderness land, cleared of Native Americans and sold by the federal government in land auctions made it not only easier, but attractive to simply use up the Upcountry land and move on when it played out. There was, in effect, little reason to farm efficiently, or with concern for the soils long-term viability.

In this game of “musical cotton chairs”, South Carolina, necessarily lost out. “The prolonged agricultural depression, highlighted by the wholesale exodus of whites, which followed the Panic of 1837 spurred concerned South Carolina leaders into action. Spearheaded by the newly-formed “State Agricultural Society of South Carolina” [which continues and still operates the South Carolina State Fair], a well-organized agricultural reform and economic diversification movement emerged during the early 1840’s” [3].

So lo and behold in 1842, the state legislature retained a “consultant”. Edmund Ruffin from Virginia, was hired to take a look at the South Carolina Upcountry and develop recommendations on how to deal with it. Ruffin concluded in his report that cotton, while the crucial driver in the past growth of South Carolina, was also responsible for its then-decline. Cotton in my words in the 1840’s “led to “deagriculturalization” (not unlike future deindustrialization). The 1840’s cotton-based economy indeed had a very short profit life cycle, given the then current-expertise.

To counter economic decline Ruffin urged that since an…

emphasis on cotton production had worn out the soil, undermined subsistence farming, and retarded economic diversification …. South Carolina should wean itself from excessive dependence on cotton by diversifying agricultural output and expanding industrial activity [4].

How ironic! Unlike most consultant reports, Ruffin’s had an afterlife. Armed with this strategy local agricultural societies sprang up across the Upcountry/Piedmont to advocate and advance agricultural/ crop/soil reforms, and secondarily, industrialization. The key to any future industrial growth, as the North had already discovered, was “connect the urban dots” ‘developmental infrastructure”. In the 1840’s, that meant railroads and city-building. The agricultural societies, .therefore, supported a number of proposed railroad projects, particularly those connecting the Upcountry, which still had limited access, to the rest of the state.

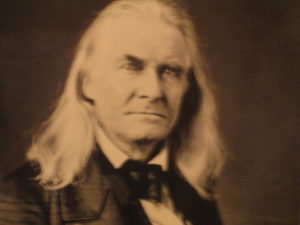

Edmund Ruffin had an after life himself. The photo above was taken after he fired the first shot at the Siege of Fort Sumter–beginning the Civil War. His past life, complicated to be sure, included his leadership in agriculture. He has been called the father of American soil science. Deeply concerned with soil erosion, initially caused by tobacco, he was an ardent conservationist, and a serious pioneer in soil improvement–promoting the use of fertilizer and lime. He founded and published the South’s leading agricultural journal, the Farmer’s Register. He was strongly opposed to agricultural mono cultures, and arrived at industrialization through the back door. But there he is–an economic developer in the 1840’s South Carolina Upcountry. A rabid state’s rights activist and an ardent proponent of slavery, he fought as a Confederate soldier despite his advanced age (he was in his sixties). After Appomattox. refusing to accept southern defeat, he committed suicide. His plantation house has since become a national historic landmark in 1964 [5].

As will be described in Module Series B, Ruffin had to have had in mind South Carolina’s national success in being the first to construct an operating railroad line in 1832. As we shall see, that railroad was promoted, partially financed, and politically supported by the Charleston Chamber of Commerce and the city’s merchant/export “cluster”. By the 1840’s the “connect the dots developmental transportation strategy”, after seeing the dramatic effect New York’s Erie Canal had on New York City’s economic development, upgraded the mode of transportation to railroads and proposed to “open up the upper South straight to the Mississippi River” to Charleston. Using modern transportation infrastructure to reach deep into the nation’s interior, a direct line to the lower Midwest/Border South would transport their goods, crops and services to Charleston for export and internal trade to other southern geographies

As our Mini-Series B will describe this was the strategy South Carolina employed to diversify its economic base and stimulate industrialization. The strategy was attempted–with mixed results–until the Civil War intervened, and General Sherman graciously put the torch to South Carolina and twisted its rails into “Sherman bow-ties”. In fairness, the copy New York strategy failed miserably before the war ever started, but it did prompt South Carolina’s internal railroad development. By the late 40’s and early 50’s “a network of railroads which would eventually revolutionize [Upcountry] transportation, and trigger a commercial boom in the region were already under construction” [6]. The Cotton Empire was learning how to live with industrialization. In a later module on the rise of the southern cotton textile industry, we shall see yet another chapter in that strategy. The womb of the cotton belt was to become an industrial cradle.

But fear not for the primacy of King Cotton. It was nothing if not resilient. After 1849, the southern Cotton Empire entered into its 1850’s glory days. During the 1850’s yet another cotton boom generated favorable cotton prices increased, causing profits to skyrocket, and prompting further expansion into the western wilderness–places like Kansas Nebraska, Arkansas and even Oklahoma. Once again cotton was not only profitable, it was the inevitable wave of the southern future. That, of course, did not take into account Yankee push-back, leading to 1860 stalemate, setting the stage for the 1860 national election.

In the meantime, cotton production in Upcountry South Carolina not only stabilized, but with soils replenished, produced 75% more cotton than a decade earlier. Long live “King Cotton”. For us, however, we need to complete our review of the rise of the Cotton Belt by first outlining in the next module the expansion of the Cotton Belt from the Piedmont Upcountries into the Deep South wilderness, and its eventual 1850’s glory days. The final module, using antebellum Alabama as a case study, will describe that state’s formation of a policy system that reflected the development of its version of the Deep South political culture.

Footnotes

[1] Lacy K. Ford, Jr. Origins of Southern Radicalism: the South Carolina Upcountry, 1800-1860 (Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 38.

[2] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Origins of Southern Radicalism, pp. 38-9.

[3] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Origins of Southern Radicalism, p. 42.

[4] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Origins of Southern Radicalism, p. 42.

[5] See Jason Phillips, Anticipating the Apocalypse: Looming Civil War (Oxford University Press, 2018)

[6] Lacy K. Ford, Jr., Origins of Southern Radicalism, p. 43.