Implementation of Alabama’s Antebellum External MED

All this palaver about migrations and political culture and their shaping of Alabama’s antebellum policy systems “hits the road” only when we tie it to the formulation and implementation of MED policy and strategy. Here goes!

In a Nutshell–Wither goes this Module

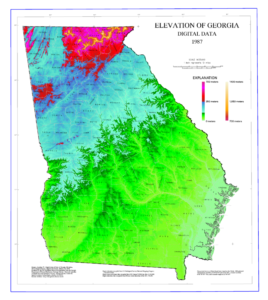

In the context of Alabama in the initial stages of a cotton boom land rush, we have discovered the state is truly an isolated wilderness being populated by whites en masse for the first time. In the midst of a land rush under-institutionalized political structures are either bypassed or unable to be accessed by most of the new emigrants. Those who arrived the earliest had access to their own financing and were able to seize take advantage of Congress and acquire dominance over the statehood and early state governance. Writing a state constitution, extraordinarily liberal and open for its time and place, the first policy system, dominated by Georgia Faction Federalists was established. It did so, however, at the peril of the impact of ongoing and future migration patterns.

In a land rush migration and settlement patterns shift fast, and in a very few short years, the Alabama settlement pattern had changed radically, in terms of geography (where) and demographics (who). Scots-Irish flooded into the Alabama highlands, and South Carolina and Georgia plantation owners, or their offspring, settled into the central Alabama Fall Line. As demonstrated in past modules, the two groupings carried with them two different political cultures. Numerically, there was no contest as to which was more impactful: the Scots-Irish significantly outnumber plantation owners and their associated groups. Taking advantage of the open Alabama representative process, they tossed out the Federalists in 1821, and in 1823 a realignment election gave the Scots-Irish dominated Democrat-Republican Party control of all three branches–control which persisted into the early 1840’s. A Second Policy System resulted.

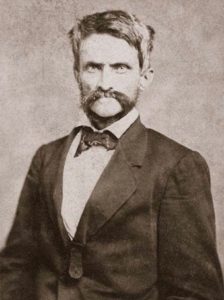

And thus begins our case study of antebellum Alabama Mainstream (MED) economic development policy. Reflecting the national landscape, the Democrat-Republican Party enjoyed one-party rule, at the cost of considerable internal fragmentation. In Alabama, however, charismatic Israel Perkins was able to mobilize Scots-Irish highlanders and keep them mobilized, to the extent other factions in the Alabama-Democrat-Republican Party could not consistently impact state policy-making–for the better part of the next fifteen years.

This vacuum permitted an almost unchecked Scots-Irish preference pattern to dominate state policy-making. Since MED was a first order priority in a new, isolated wilderness state, that meant MED would reflect the goals, beliefs, and values of the second policy system’s dominant political culture. Accordingly, we would get a rare chance to see what this political culture expected from MED in that time period, and in that particular geography. As we shall see, the Scots-Irish version of MED focused almost entirely on banking and the State Bank, and treated “connect the dots external developmental transportation infrastructure” roughly–at a time when most of the nation reversed the preferences. Why this is so consumes a great deal of this module.

It also meant that the South Carolina, or Georgia political cultures would not be cloned in the newly-settled Alabama. The surprising result, however, was that for various reasons to be discussed below, the intensity and duration of the Scots-Irish preference pattern created a long-term cultural heritage that set major state-level policy parameters that persisted into the 20th Century–in effect, the Scots-Irish preference pattern had developed into a “paradigm” and was institutionalized into state policy-making. The latter assertion will be picked up in later modules in future Themes.

Alabama’s First ED Priority: Yeoman Agricultural Lending and the Alabama State Bank

What follows below is an assessment of Mainstream ED (MED) as handled by Alabama’s first, second, and perhaps third policy systems (1819 to 1860). Until the Whigs jelled in the mid-1830’s, Scots-Irish Democrats dominated, not exclusively by any means, the agenda and much of Alabama’s politics. In this we see a rare example of a single political culture’s approach to MED and how it impacted state politics for the better part of three decades.

The past Federalist use of state-chartered corporations in state-building was immediately challenged by the Democratic Party and its charismatic governor, Israel Pickens. What previously had been a near-automatic decision to use a state-chartered corporation for banking or internal improvements became a highly-charged, and incredibly polarizing, partisan issue. In the immediate aftermath of 1812 war’s end, an Democrat alternative to the state-chartered corporation appeared–in the form of a government corporation empowered to finance/construct New York’s Erie Canal. Pickens demanded a “State Bank” accountable to government, and operated by government bureaucrats, as the state’s primary banking institution. Bernie Sanders couldn’t be more happy with that choice.

the Alabama State Bank and Alabama’s Transition into a Second Policy System

When William Bibb (Democrat-Republican, a Georgia-born descendant of Tidewater plantation owners, leader of the Georgia Faction) became Alabama’s first governor in 1819 he confronted immediate pressures to formally establish a state-level bank. Alabama’s defacto state bank, the Planters and Merchants Bank, was privately-managed, in structure a state-chartered corporation with private management–the Federalist preferred EDO. The Planters and Merchants Bank founded by Georgia Faction plantation owners during the state’s initial settlement was a key hub in Bibb’s constituency.

The Planters and Merchants bore the brunt of agricultural lending during the early Cotton Belt rush. The crushing 1819 Panic hit Alabama hard, with its effects most pronounced on the hardscrabble Scots-Irish yeoman farmers in the highland counties–where the Planters & Merchants was dominant.

With hopes and dreams badly frustrated by the Panic, former hardscrabble squatters who had assumed considerable debt to purchase their land in auction sales were simply devastated, others were still in need of loans/credit to acquire their homestead. Highland yeomen farmers were in crisis. Plantation owners, secure in their financial and social position, were better able to sustain their operations until the Panic abated.

With so many swimming in debt, the Huntsville-based Planters and Merchants Bank, “suspended specie payments”, i.e. Alabama local currency which debtors used to pay their mortgages–creating an instant liquidity crisis. To compound matters, bank management was charged with mixing private money with bank funds [1]. If that were not sufficient, the state legislature, led by the Georgia Faction, had in 1818 suspended the state’s usury law, and that was seen by many as responsible for the rapidly escalating interest rates. In no time, the Planters & Merchants had become ground zero, the focus point of Scots-Irish yeoman farmers concerns and solutions to the economic and financial crisis.

Economic distress (bankruptcies, and farm foreclosures) associated with the Panic, irretrievably linked to (state-chartered) banks, cast the private management of state-chartered banks into the spotlight. To those who believed their mortgage was in the public interest”, or beyond the pale of bank profit goals, the “structure” which permitted private management of a public institution became an easy target.

(T)he hostility toward corporate enterprise and the fear of monopoly animated the small farmer on the frontier … .The most unlettered farmers recognized that state government [had] befriended the bankers … [2].

Bibb initially resisted pressure on his state-chartered bank, but dying in late 1821 he was replaced by Henry Chambers, a director of the (Huntsville) Planters and Merchants Bank in the 1821 election. In the election Chambers was “crushed” by Israel Pickens 9616 to 7129. Have no fear, the Georgia Faction, renamed the “Royal Party” by its opponents, remained a considerable force in the new policy system that followed the 1823 realignment.

Israel Pickens Forms the Second Policy System

Democrat-Republican Pickens, campaigning as “champion of the people”, appealed to distressed highland Alabamians. An owner of a startup bank, he had successfully navigated the Panic. Asserting he could reverse economic decline by taking the state’s economy out of private sector control, he blamed the state-charter for permitting the bank to become a den of elites using public resources for personal benefit, and he resolved to do better. He proposed as an alternative a government-operated lending institution.

Pickens took office in 1822 and a state bank was quickly approved by the legislature–but it was privately managed. Pickens vetoed it. In 1823 similar legislation was proposed, but tabled due to Picken’s opposition. The 1823 election, however, not only returned Pickens to office, but also resulted in a Scots-Irish/Democrat-Republican controlled state legislature–marking the election as a realignment–the effective end of the short-lived first Alabama policy system. To complete the realignment the state was reapportioned in 1825, a long-standing Picken’s pledge to reflect the migration flow and land rush.

Finally, in 1824 with a cooperative legislature Pickens got the state banking bill he wanted. The money that funded it ($200,000) was diverted from a fund to create a state university. In any case, the Bank would be managed by a President and a Board of Directions chosen annually by the state legislature, already well-known for its cronyism and patronage. The governor’s brother became the Bank’s first President.

Why the reader may ask did the state-run Bank appeal to the Scots-Irish? Decisions made by experts–or worse the wealthy–commanded little respect from the Scots-Irish hardscrabble working class. The legislature was the nearest thing in government to the voice of the people, and the democracy of the common man was usually more offended by expertise than determined to use it [3]. The needs and opinions of the “common man”, today’s so-called “American people” were their reference point for decision-making.

Equally important was to the Alabama Scots-Irish the State Bank was more than just a bank; it was the MED yeoman farmer needed–and wanted– from Alabama state government at that time. To the Scots-Irish, if banking had to be established, than it better be available and accessible to them–it could not be spun off to the private sector to manage or independently operate. It had to be entrusted to a public (state) EDO that was accountable to them. Scots-Irish’s top priority amid an ongoing Cotton Boom land rush/Panic was not internal improvements, but accountable finance and lending. Their fear of losing control set the tenor of Second Policy System politics, and the lyrics of that policy debate never strayed far from who would control the State Bank, and regulate the other banks.

So, in 1825 the legislature revoked the Planters and Merchants Bank charter. Mission accomplished, Pickens did not run for governor in the 1825 election. He ran and was elected to the U.S. Senate. He did not complete his term, becoming ill, resigning, and spending his last days in Cuba where he died in 1827.

In any event, subsequent governors/state legislators relied on the State Bank to provide capital/land loans for “frontier yeomen” and fledgling, aspirant, planters. This consumed scarce state resources, and from the start limited government services. Since low taxes were bedrock demands from nearly all economic classes, limited state services and low taxes became the second policy system’s principal electoral pillars. Accordingly “social welfare schemes [including education], even internal improvement projects, were wholly foreign to the government of antebellum Alabama” [4].

How the “State Bank” and Low Taxes/Few Services Became a Paradigm

The Second Policy System, dominated by the fledgling, internal divided Democrat Party, could never escape from its reluctance to impose taxes. Combined with a clear rhetorical commitment to limited government, it defining state’s core service function to the wishes of its hardscrabble electorate: help the yeoman farmer and facilitate the development of the cotton economy. The State Bank, responsive to elected officials, was what antebellum Alabama MED came to be.

The Jacksonian Democrats, able to consistently mobilize their constituency by alluding to the “Royal Party” and repeat the horrible tales of Panic of 1819 private banks, were able to focus each election on the threat de jour against the State Bank. Over several decades this issue and the values and beliefs surrounding it became embedded into the culture of Alabama politics. Accordingly, the Royal Party has seemingly never died in Alabama. Its memories are inserted deeply into the state’s dominant political culture, and they haunted state politics, probably to this very day.

[It was as if] the Royal Party [Georgia Faction] was real–as real as irrational hatred or an unnamed fear. It was the embodiment of all the insecurity of small farmers in the midst of plantations, of the poor in the midst of plenty, of a new state in the midst of old. It was an entity to whom the defiant affirmation could be made that in a democracy, numbers count …. the war against the phantasmal royal party gave the mass of Alabamians something … more valuable. It gave them a crusade–the sense that, through cooperative [i.e. mobilized] political action, they could command their destiny[5].

Part of the reason that this anti-bank jihad persisted and became embedded was thanks to its contrast with a branch of the U.S. National Bank which opened in 1831 Mobile. Little-known today the successor to Hamilton’s National Bank had become a major player in financing the Cotton Belt expansion.

Between 1824 and 1832 (the years during which Jackson’s feud with the Bank played out in Washington) the National Bank increased its Cotton Belt portfolio by 1600%–by 1832 about one-third of the National Bank portfolio was allocated to the Cotton Belt. It’s huge presence in that risky agricultural gazelle provided credibility and legitimacy for foreign lenders who also enlarged their presence. The National Bank, in place of weak and under-funded state banks, laid the financial foundation of the American Cotton Belt [6].

The federal bank, more professional and responsible, implicitly challenged the activities of the State Bank, and provided capital to major plantation owners, the chief constituency of the Royal Party. Cream-skimming the best of Alabama’s loans, it left to the State Bank the far more vulnerable risky yeoman mortgages. Not only that, the National Bank branch put a damper on the volume of State Bank loans, and, since they were not financially eligible for National Bank lending was therefore seen by capital-starved yeomen farmers as yet another “chartered” enemy. We won’t even mention how it triggered discussion around what became “states rights”. States Rights really tapped into the Scots-Irish political culture–but that is another story entirely.

The legislature made several attempts to approve legislation, and they and the governor went on record to urge their Congressional Delegation to end the National Bank charter. All to no avail. It did, however, keep the State Bank on the top of the state’s policy agenda until the 1837 Panic.

When the Panic of 1837 hit, the State Bank, along with every other financial institution in the nation, was considerably troubled. The state and the State Bank never formally defaulted on its debt. But over the next decade or so its weaknesses and efforts to reform it dominated Alabama state politics.

the State Bank and the Panic of 1837

As a state agency, the State Bank suffered from many of the alleged diseases that inflict public bureaucracies: outright corruption, patronage, poor and inconsistent management, and in lending insufficient due diligence and portfolio management. In the latter instance, the State Bank’s competition with the National Bank had led the former to loosen its lending terms and conditions to become a “more flexible” alternative to the plantation owners. Ironically, the larger loans to plantation owners proved more troublesome than the more vulnerable mortgages to yeoman farmers.

The state had accumulated over $15 million in debt, but the legislature raised taxes, cut spending, and in general used all sorts of financial jerry-rigging to keep the institution intact. In that atmosphere, internal improvements became linked with alleged excessive state expenditures, but were criticized not only for their fiscal deficiencies, but for the “corruption” of log-rolling to assist small road improvements and the profiting of local “fat cats”.

It was in this period–after the Panic of 1837–that the newly-emerging Whigs attempted to influence state policy-making to effect legislation to advance internal improvements. As we shall see, they enjoyed very limited success, and the Second Policy System’s MED paradigm weathered that storm fairly well.

Internal Improvements, State-Chartered Corporations Fall Off the Policy Agenda

Antebellum Alabama Scots-Irish never warmed up to internal improvements. To them internal improvements benefited the private sector, and it was their responsibility to implement the strategy. When the public sector got involved, it usually meant taxpayer dollars winding up in the coffers of the proverbial fat cat. That perception accounts for much of their opposition to state-chartered corporations–or hybrid public-private EDOs. If the public had to play a role, than a public agency should implement the project. The major exception is a post-Panic receptivity to infrastructure as a way to dig out of debt and restore household prosperity through economic growth. In a nutshell that is what you are likely to get from this section. As you will see in the next mini-series of developmental infrastructure, that holds true for South Carolina as well.

Specifically, internal improvements included roads, bridges, river improvements, canals and startup railroad companies. The state-chartered stigma which finished off the First Policy system’s state-chartered was perceived as little more than a legal ruse, a semantic subterfuge that allowed wealthy elites to become parasites on the hard-working agricultural working class. That line of thinking, thirty years previous to Marx, opened up in Alabama a political rhetoric that could be described as the most outrageous, fanciful personifications of class opposition to Early Republic capitalism. Anything remotely related to its elites, and extended to the alleged social changes that progress and so-called change supposedly wrought was injected into antebellum political rhetoric. Anchoring all this was a deep resentment against taxes–that was, and still is, the third rail of most Deep South elections.

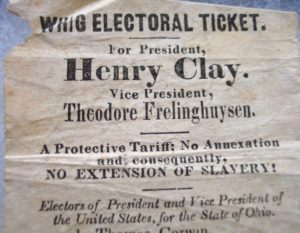

The newly-formed Whig Party, composed mostly of planters and their associated commercial nexus (located in larger port cities) challenged the Scots-Irish. Personalistic and opportunistic, the Whigs sustained a political opposition that won its occasional victories. Internal improvements were arguably the chief item on their local/state policy agenda.

Andrew Jackson carried Alabama on his march to the Presidency in 1828, but those who opposed the general and supported the policies of Henry Clay were quietly coalescing into an opposition that later evolved into the [Alabama] Whig Party. Many of these men were engaged in commercial operations … Whiggish attitudes had a strong following in the large slaveholding areas of the southern Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley, and among the merchants in the towns, [and] especially in Mobile [7].

The state in the 1820’s intermittently provided some state assistance to a few internal improvements (roads and canals). In 1824 an Internal Improvement Bureau (state) was created. The net effect of these small improvements were marginal at best. A resurgent Jacksonian populism of the early 1830’s, however hardened Scots-Irish anti-capitalist inclinations. So the State Board of Internal Improvements was terminated in 1832 [8].

The Panic of 1837 unleashed a mixed bag of disillusionment with state banking, but intensified the class schism. “Class hatred and fear of corporate wealth [evolved into] a continuing theme in Alabama history …. capitalists were the enemy of the common man“[9]. Since Whigs were identified by Scots-Irish as capitalist advocates, whatever Whigs proposed in internal improvements could be “spun” by Democrats into some sinister machination. Though Whigs captured the Senate between 1849 and 1853, they never elected anyone to state-level office. Usually, Democrats elected 55 House seats to the Whigs 45.

But one wonders, why were the Scots-Irish comfortable with their geographic isolation? Perhaps it was that Scots-Irish identified “freedom” with their personal individual freedom; they resented any force or power that limited their own individual autonomy or freedom to take action. Geographic isolation in that context inhibited challenges to personal freedom and autonomy:

Alabama farmers seem always to have been fearful for their freedom. {Border people] the fewer the contacts they had with the world, the better they liked it. They sought individual autonomy. [Preferring barter] They resented the necessity of dealing with bank-made paper; they resented the necessity of buying their land from the government; they resented the necessity of paying taxes, and otherwise encountering the state … When power impinged on their lives, they reacted with suspicion and perturbation [10] .

Nevertheless in that brief policy window (1824-1832) internal improvement projects were attempted. The Pickens-led North Carolina faction, while unwilling and unable to find state funds for internal improvements, were not adverse to federal monies. Congressman Gabriel Moore secured federal financing in the form of 400,000 acres of land grants to support navigation improvements on the vital northern river, the Tennessee. After 1832 several legislators/governors proposed some state involvement in internal improvements, but no initiatives of any scale or cost were approved previous to 1850.

When Moore became Governor in 1829 he secured some state financing for a short (two mile) canal that partially opened up the Muscle Shoals rapids–but it was a marginal improvement at best [11]. Only with the opening by rail (see below) was northern Alabama and the Tennessee River opened up to access New Orleans for cotton-export. Moore’s congressional successor, Dixon Hall Lewis, shut off any other federal assistance because states rights had become a major Alabama Democratic Party issue and internal improvements, in case you didn’t know it, was an avenue for federal tyranny:

Lewis campaigned for Congress opposing federal aid for internal improvements, a surprising stand for a district depending upon river commerce … Lewis preached that federal aid could only bring despotic federal control that would impinge upon the people’s liberty [12]

That internal improvements could be successfully relegated to a secondary priority was made possible by the existence of a purely privately-financed and operated developmental transportation mode/ infrastructure: the steamboat. Without the steamboat–which first reached the Cahaba in central Alabama Fall Line (the first state capital until 1825) in 1822–was cotton able to to exported to far-away Mobile (150 miles distant). It was to the steamboat that Mobile must attribute its Cotton Belt prominence, and it was the steamboat that allowed the cotton export economy to work its wonders. Without the steamboat, even the 1840’s Alabama remained remarkably isolated, and land-based internal transportation was not well-developed.

So, for all practical purposes, Alabama did not engage in serious canal-building, unlike the North and coastal southern states. Roads and bridges were local affairs, as were river improvements.

Alabama Antebellum Age of Railroads

Railroads, if anything, hardened Scots-Irish opposition to internal improvements. “From the beginning Whigs favored [state aid to railroad initiatives] and Democrats did not … Democrats did not doubt that railroads would improve communication and strengthen the economy. But they feared the power that corporate wealth would thus gain in the life of the state. They believed that ‘money governs despite laws and constitutions’“(13) Even in the post-1850 golden Age of Railroads, Alabama Democrats continued to perceive public private partnerships as “chartered monopolies and associated wealth” that enabled “corporate wealth [to manipulate] the State“.

In response to a 1849 railroad request for state financial participation in a rail project, legislative Democrats opined:

A corporation that is a co-partnership without soul or body, is formed and presents itself before the Legislature … expressing the greatest compassion … kindly proposes to extend a helping hand to develope (sic) their resources … upon the simple condition that said benighted people should first develope two and one half million dollars … for special benefit … [The answer is] No if we have not the internal improvements that older states can boast of, let us be able to glory that Alabama … knows no creditor, and has a population neither seeking nor needing the patronage of State credit” [14].

Alabama entrepreneurs always lacked access to capital pre-1850. Without Georgia investors, Alabama would not have had any serious rail line in operation previous to 1850. Absent established centers like Charleston or Savannah, Alabama municipal/county level policy systems, excepting Mobile, were too small and fragile to seriously pursue governmental-led MED. Alabama-based railroad initiatives fared poorly in state politics.

The exceptional lack of Alabama urbanization rendered Alabama-centered railroad projects almost financially infeasible. As late as 1850 there were only ten Alabama urban centers with a population exceeding 1,000. One half of its fifty-two counties did not have an urban center which exceeded 500 residents. Mobile with 22,000 was the largest city, and Montgomery (the state capital) second with 5,000 [15]. The burden of MED of necessity, fell to the state–and the state wanted as little to do with it as possible.

Thus, Alabama participated minimally in the Age of Railroads, placing among the last of southern states in track mileage.

Alabama’s first successful railroad, the Tuscumbia Railway (in fact it alleges to be the first railroad operating west of the Alleghenies, 1832) appears to have been financed and built by local merchants who operated the landing/pier on the Tennessee River. The Railway was a state-chartered corporation, but appears to have been privately financed by Georgia Faction well-heeled plantation owners and merchants.

The initial railroad was barely two miles long, used horses, but bypassed a major Muscle Shoals rapids and rocky shallow fast water that served as a barrier to accessing northern Tennessee River areas. With the railroad bypass much of Alabama’s Tennessee River Valley could ship cotton directly to New Orleans on the Tennessee. The railroad extended directly to Decatur, near the Georgia border (45 miles) two years later and by 1851 connected to the Memphis and Charleston RR which was completed in 1858.

Still, Alabama did enjoy a burst of railroad development during the 1850’s. All of these railroad initiatives, although many generated some response by Alabama entrepreneurs, were financed, managed, and proposed by railroads external to Alabama. As we discovered in Theme 1, this burst of railroad enthusiasm was the result of Stephen Douglas’s north-south transcontinental 1851 federal legislation. Desirous of unifying the the northern and southern economic bases (and hopefully avoiding a civil war), the federal government provided an array of land grants, and guaranteed federal loans.

Guaranteed loans and land grants from Stephen Douglas’s transcontinental railroad legislation (see Theme 1) provided access to desperately needed funds and free land and liberal rights of access. That federal funded resuscitated a private Montgomery-based railroad initiative that had began in 1832 with an Alabama state corporation charter, and continued in fits and starts, popular local subscriptions until the line extended for nearly thirty-two miles by 1840.

Then it failed, and efforts to reorganize and restart the project, including $400,000 popular subscriptions and state legislation which tied its financial management and construction to, of all things, the troubled, post Panic of 1837 State Bank, kept the project on life support–barely. And then the federal initiative provided a new financial source to complete the reorganized Atlanta and West Point RR to open in 1851-3. At that point, a distrustful Alabama state legislature, using powers included in the state-charter, placed the profit-making railroad under state fiscal watch and oversight. The owners were required to personally guarantee their financial administration. Despite this negative regulatory environment, the line expanded, remained profitable

During the Civil War the line was raided by the federals eleven times, including one (Wilson’s Raid) which carried over the lines entire rolling stock. By war’s end the railroad was effectively non-functional

More transformative and impactful were fresh initiatives triggered by the federal legislation. Loans guaranteed by the federal government not only benefited the Montgomery and West Point line, but were successfully used by the Alabama and Florida (A&F) which linked Montgomery to Pensacola Florida in 1861. Suddenly Montgomery became a rail hub. The A&F was owned by Illinois (Peoria) investors and was intended to link up with the Illinois Central. Meanwhile, the Illinois Central created a direct subsidiary, the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, using federal land grants as well as guaranteed loans opened its 260 mile line connecting Mobile with Columbus KY in 1861.

The astute reader will notice the above paragraphs contains no reference to Alabama state involvement. Even with an organized and active Whig opposition, in the golden years of antebellum railroads, the Alabama state government remained closely tied to its now long-standing opposition to state involvement in internal improvements.

Governor John Winston, 1853-57, (, the so-called “Veto Governor” effectively laid down on state railroad tracks and refused to allow state funds to be used for such purposes. “Wielding the [Veto] so many times, mostly on bills providing state aid to railroads [,] he believed that railroad development should be by private investment and that the state was too much in debt (from the failure of the state bank) to incur more bonded obligations” [16] . In particular, he vetoed the $400,000 state loan to the Mobile & Ohio (see above)–despite the commitment of the City of Mobile which invested $1.1 million in the railroad and the federal government had made it considerable land grants.

In a very rare instance, the state legislature overturned his veto.

We end on a happy note!

Footnotes

[1] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, (University of Alabama Press, 1994), pp. 74-5.

[2] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p.75.

[3] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p. 80.

[4] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, (Louisiana State University Press, 1978), p. 19.

[5] Lewy Dorman, Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 through 1860 (University of Alabama Press, 1995), p.15.

[6} Edward Baptist, the Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (Basic Books, 2016).

[7] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p. 87.

[8] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p. 50.

[9] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p. 87.

[10] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, p. 54.

[11] William E. Martin, Internal Improvements in Alabama, Forgotten Books, February 2018, originally published 1902]

[12] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, pp. 50-1.

[13] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, p. 51

[14] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, p. 19.

[15] J. Mills Thornton, Politics and Power in a Slave Society, p.52.

[16] William Rogers, et al, Alabama: the History of a Deep South State, p. 166.

Optional: State-building and Banking

Accordingly, our first discussion is how banks and finance system fit into our conception of state and local ED. Once we do that we can move on to how and why Alabama dealt with its version of MED. The reader will in time discover that the crisis caused by Alabama establishing its initial state bank, has its roots in the assertion by Alabama’s dominant cultural group, the Scots-Irish, of its concerns and preferences in the matter.

The first task in every Early Republic state was to set up its financial and lending system (insurance as well). Whether or not one should label this as “economic development” is perhaps debatable. But Hamilton, considered a national-level economic developer precisely for his role in establishing a national banking and finance system, suggests the matter need be discussed when we refocus our attention to the state-level. States in our federal system are constitutionally “sovereign” in clearly specified policy areas which include both banking and finance. State involvement, therefore, in the initial establishment of a banking and finance system is, in my eyes, a legitimate and critical economic development function/ strategy.

No one is likely to argue that banking and finance is not fundamental to economic development. That establishment of a banking/finance system “is” economic development is more complex. Like city-building, my Chapter One Model can easily include in the “state-building” strategy, the initial establishment of a banking-finance system, a one-time strategy of uncertain temporal duration, should be considered as a core, if primeval, ED strategy-function. As a core element of state-building, as well as nation-building. Once suitably “established”, and that could (and did) take decades, the strategy had been achieved, and is spun off to become its own policy area, separate, but critically related to economic development. To the extent the banking “wheel” has to be reinvented some time in the future, I leave to others.

Hamilton’s National Bank was a public EDO, the national equivalent of a state-chartered corporation. Congress, not the state-legislature, approved its charter. Older coastal urban centers/states had long since dealt with capital accumulation and the establishment of core lending and finance institutions using privately-managed state-chartered corporations. This is what Bibb and the federalist Georgia Faction had done with their bank previous to Alabama statehood.

Lacking institutionalized political parties previous to the Election of 1800, Federalists dominated state and local governments, not only because of their association with the Revolution and the new Republic, but because their opposition, usually referred to as “anti-Federalists” were ill-organized and their leadership typically more “populist” than the educated older wealth Federalists who dominated most state and local politics and economic actors [1]. Always distrustful of banks–and almost anything association with industrial finance and capitalism–anti-Federalists were unable to stop Hamilton and his state and local imitators. By the second decade, that disorganization ended. The Democratic-Republican Party inherited much of the anti-Federalist agenda, and dispirited former Federalists fought a rear-guard action.

As former anti-Federalists developed their economic development principles and agenda, a period of transition during the first decade followed. Jefferson struggled not only with tariffs, but with whether he constitutionally could/should complete the Louisiana Purchase, and should he react to the report given him by Lewis and Clark. In Theme 1 we discussed his on-again, off-again relationship with Albert Gallatin and Gallatin’s first national ED plan, with its reliance on federal involvement, if not leadership, in “connecting the dots” internal improvements. The Napoleonic Wars consumed much policy attention–and it involved tariffs and blockades–and the War of 1812 simply overwhelmed MED as a national or state primary agenda concern.

At the war’s end in 1816 MED quickly surfaced as a major policy issue, particularly in state and local policy systems. As the Union expanded by admitting more states, the issue of state-building necessarily rose to the top of the policy agenda heap. Alabama after 1819 never quite got its hands around its economic-related state-building, and that pushed MED off the policy agenda for decades–actually more than a half-century.

For new states such as Alabama, state-building topped internal improvements; bank and finance systems had to be established first–they, for example were the ones to finance internal improvements. The two strategies (banking/state-building and internal improvements) were closely linked, but more salient to our next discussion, both shared their paradigmatic reliance on a state-chartered corporation as the EDO of choice. That was soon to change.

The past Federalist use of state-chartered corporations was challenged by the rise of the Democratic Party. What previously had been a near-automatic decision to use a state-chartered corporation for banking or internal improvements became a highly-charged, and incredibly polarizing, partisan issue. In the immediate aftermath of 1812 war’s end, an alternative to the state-chartered corporation appeared–in the form of a government corporation empowered to finance/construct New York’s Erie Canal. Dewitt Clinton (his uncle and mentor, George Clinton was Madison’s 1808 VP) was a Democrat-Republican.

Alabama became a state a few years after the War of 1812 ended. Described nationally as the “Era of Good Feelings”, the United States, the proverbial two-party democracy, for a generation possessed only one macro political party which for simplicity’s sake we refer to as the Democratic Party. Former Federalists, (the Federalist Party did not disappear completely) became Democrats, and the observer by the 1820’s could see any number of conflicting ideas, platforms, and personalities within that grande melange. Factions, in effect became political parties.

One faction, populated chiefly by former Federalists and their successors, would eventually jell into the little-known Whig Party (named after the English Whig Party), arguably led by Henry Clay. Before 1860, the Whigs would, at least technically, elect four presidents. The Whig Party jelled during the 1830’s, largely in reaction to Andrew Jackson, whose adherents remained in, and usually dominated the Democratic Party.

Economic development, both federal and state/local was a major policy area that defined one as a Whig or Democrat–hence this history cannot ignore how this partisan divide affected our history of S&L ED. The one-party Era of Good Feelings and the emergence of the Whig Party in reaction to Jackson plays out throughout this module. Jackson, one cannot forget, was a major player in the rise and expansion of the Cotton Belt–and he was an Alabama property owner who was personally well-known to Alabama’s political leadership, and Jackson was not infrequently involved in its politics.

[1] See Herbert J. Storing, What the Anti-Federalists were For, (University of Chicago Press, 1981), p. 46