South Carolina Attempts to be the New York of the South

Charleston’s Hinterland Imperialism: The 1850’s Blue Ridge RR

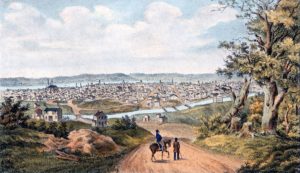

New York City’s “take off” benefited enormously from Erie Canal’s connection to the Great Lakes hinterland. The issue in this section is whether Charleston could replicate New York and “chase” is expanding Cotton Belt hinterland.

The Erie Canal relied on New York capital and taxpayers dollars (it was a state-run canal company) and was wholly contained within the state. It did not require approvals from other states. The SCC&RR had successfully overcame the multi-state issue–stimulating Georgia competition in the process, while significantly losing time and increasing costs.

On top of that, 1850 was no longer the age of canals; it was the age of railroads, an industrial technological nexus, that was by that time more mature, and galloping into an industrial-manufacturing age of considerable innovation and disruption. This is itself added one more element to South Carolina and the Deep South’s need to compete to preserve its own way of life and its agricultural economic base.

The historical reality is that South Carolina tried.

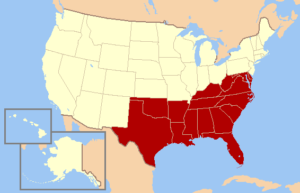

Culling out several observations from previous modules, Charleston (and later New Orleans) were the only coastal ports of size that could launch an imperialistic hinterland access strategy similar to the port cities north of the Mason-Dixon line. Charleston’s SCC&RR led the nation in establishing the nation’s first operating rail line in 1832-3–but as we have already hinted, that success only shored up its access to the central South Carolina hinterland, doing little to chase the non-Carolina Cotton Belt hinterland..

Charleston was under considerable pressure to chase cotton production as it extended into the Deep South–evidence of export decline was notable by 1850. South Carolina as a state by 1850 had a dog in the game; it too would clearly suffer. Upstart Savannah had pretensions and in 1836 had launched her own imperialistic railway: the Western & Atlantic. Whatever “divided mind” the two political cultures exerted on South Carolina’s policy process, growth after the depressing, long-lasting Panic of 1837 was a popular antidote to debt and decline. Finally, the 1850’s was the decade of southern railroads–the timing was perfect.

South Carolina failed in its attempt. Charleston’s domestic business community, long-dominated by foreign export/logistics/finance sectors, hollowed out by slavery’s self-sufficient plantation economy was slowly developing by the 1850’s. What FDI the south attracted, and it was considerable, was applied to finance expansion/production of the Cotton Belt; infrastructure financing remained risky in a rural economy, even if technology had matured. However intensely it wanted to reverse decline, or be stimulated by Savannah-New Orleans urban competition, Charleston lacked the resources for financing a hinterland imperialist developmental transportation infrastructure strategy.

The value of this case study lies in understanding how and why it failed. provides an excellent understanding of the complexities incurred in financing and constructing a multi-state developmental infrastructure railroad in a region lacking established investment capital–and confronting an unappreciated major obstacle.

SCC&RR’s 1835 Hinterland Infrastructure Strategy

SCC&RR probably had multi-state, “New York of the South” ambitions as early as the late 1820’s. The first step was the Hamburg line. Once opened, SCC&RR pivoted and along with its Charleston business community allies enlarged the business plant by redefining its ultimate goal as accessing the nation’s interior, crossing over the Appalachians, to extend its reach into the grain-producing areas of Tennessee and North Carolina–and southern Ohio.

The Charleston Courier called it “a bold conception”, and a “magnificent project” that would make Charleston “the Commercial Emporium of the South” in which southern rice and cotton would be exchanged for western meat and grain. Charleston would be the export outlet for the south central Midwest, and through trade Mid westerners’ would come to appreciate the value and importance of southern institutions and its way of life (slavery, of course) [1]. They also hoped to extend SCC&RR into other parts of South Carolina, from Aiken to Columbia (north) and then into North Carolina.

For the most part in this time period, the developmental transportation infrastructure strategy was locally inspired and driven. The smallest of settlements had ambitions, and as the railroad alternative to canals/roads matured, entrepreneurs appeared in even the most unlikely of cities. Access to national markets, and the status and economic potential of having that access attracted followers and investors–and media. SCC&RR was the nation’s first established line, and that captured the attention of neighboring–and not-so-neighboring cities/settlements and states.

Natives in these areas were intrigued, and several overtures were made inviting SCC&RR to include them in their plans. So in September, 1832, months previous to the line’s formal opening, SCC&RR held a “convention” of those interested was held at Asheville, NC; attended by 8 representatives from 4 Tennessee counties, and 20 from 8 counties in North Carolina.

Committees for each state were formed, to measure public support and secure support from state legislatures. The convention sent a request to the President asking him to appoint an engineer to survey and report on routes/topography. The President concurred so long as the cost, about $3,000, was paid by the states. South Carolina quickly appropriated its third, but the other states, for their own reasons did not. Interest in the project by these state governments was minimal at this point (excepting Georgia, see the next module).

The effort continued–but SCC&RR decided not to put its eggs in one basket.

Accordingly, SCC&RR refocused, and adjusted its business plan to extending itself into northern South Carolina by conducting another capital subscription for 3,000 shares to finance extension of a line to Columbia (it received applications for over 6,000 shares so great was the interest), the state capital, and largest interior South Carolina urban center. Charleston merchants, heavily involved in the establishment of a new state bank, financed by yet another subscription for over $2 million, were intending that bank would also be a financial partner in this and other railroad endeavors. The business community was sincerely trying to develop its financial capacity to fund business investment and railroad-waterfront infrastructure.

Cincinnati by 1835, however, had generated its own domestic (business-led) lobby to explore a line connecting it to the Atlantic. Its initial survey determined the southern route over the mountains more cost-effective than a Pennsylvania or Virginia route. At Cincinnati’s request, the Charleston City Council, hard-pressed by its Chamber called for a public meeting in Oct 1835 to discuss and make recommendations on how to proceed. Charleston’s chief proponent was the retired former U.S. Senator and Governor, Robert Hayne. His entrepreneurship and zealotry sustained the project. His death in 1839, combined with the Panic, probably killed it.

Cincinnati argued that it was committed to the project–that central states required an opening to the Atlantic if they were to grow; that commerce would yield revenues to pay its costs; that technically routes existed that were cost-effective construction-wise; that other states would participate; and the terminus should be Charleston. Charleston was impressed so it took charge of the endeavor. The initial costs (a survey/topographic study) were borne by the South Carolina legislature pressured by Charleston city council, chamber, and business community.

No other state joined in at this stage and the survey report, sketched out two possible routes to Cincinnati–both with serious “incline” issues. Knoxville was common mid-point to both. The states of interest at this point were: South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Interestingly, although Cincinnati was the proposed terminus, and the initial proponent of the project–and despite the fact the project would press forward for more than half a decade–Cincinnati did not put an additional dime into its finances, or legislative support for the terminus.

In any case in December, 1835 the South Carolina state legislature amazingly took the lead and approved a new state-chartered corporation to develop/manage/operate the proposed project: the Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company, later amended to the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company.

The State authorized a subscription (sale of stock) for $6 million, and a minimum of $4 million was required to commence operations. That number, however, was only a fraction of the total cost of the proposed project. The charter was to run for 36 years, and required participation of the other states and enactment of congruent legislation. A perpetual tax abatement was approved. The states of North Carolina and Tennessee also approved subsidiary charters for the South Carolina state corporation by the end of 1836. Kentucky, however, sensitive to the Louisville KY-Cincinnati rivalry, demanded the line run simultaneously to Louisville (which explains the name change for the railroad).

To tackle the next steps, a meeting was held in Knoxville (July 4, 1836). About 400 individuals attended, representing nine states. It elected Hayne its permanent chair, and appointed a 45 member executive committee to conduct planning and operations. In the course of the meeting, 45 representatives from Georgia met in an adjoining room, prepared a report to submit to the meeting which made the case for a Georgia terminus, and line that ran through Georgia, not South Carolina. In the ensuing discussion, a compromise was attempted, but that proved unsatisfactory to the Georgians.

Returning home, the Georgians held their own convention and developed an initiative which culminated in the building of the Western and Atlantic Railroad, a government-owned railroad. The Georgia railroad began in Atlanta, which was virtually unsettled in 1836, and ran to Chattanooga, TN. That line was successfully built–by 1851–and, still state government-owned, is operating today leased to CSX. On this line in 1862, the famous “Great Locomotive Chase” by Walt Disney and Fess Parker occurred. More on that in the next module

The convention, despite the Georgia shenanigans, was a success. Hayne, now in total charge, began a series of speeches, reports, and press releases which certainly can be described as “boosterism”–to generate support no doubt–but to more importantly boost the sale of stock which began in Oct 1836. Senator John C. Calhoun, questioning the proposed route, decided to personally inspect it, and successfully demanded a route change that he deemed better. Political support was falling in line for the initiative.

By November, Hayne announced that South Carolina planter Wade Hampton Sr. purchased an additional $50,000 in stock putting them over the required $4 million minimum to become active and operational as a state-chartered corporation. Hayne then campaigned in the other participating state legislatures to buy stock as well. The Charleston Courier reported the announcement declaring “The glory of the enterprise belongs to South Carolina and South Carolinian’s‘” [2]. It was at this point that “reality bit”–hard.

Four million was a drop in the bucket. It was not enough to acquire land and start construction. When investors looked about, the Georgia was now an active competitor, and railroads from Pennsylvania and Baltimore were also in construction to open up the Midwest as well. Virginia, opposed to Baltimore, was also threatening to join in. States and cities were pressed to buy stock; many did, but nowhere near enough to start. So Hayne concocted “a great scheme” to solve the financial crisis.

He proposed South Carolina authorize a state-chartered bank whose purpose was to raise funds to finance stock sale–as what today would be a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Company. With considerable reluctance, the State agreed, providing that at least two other states would join. If they did the Southwestern Railroad Bank would be authorized to raise $12 million starting in 1837. The debt of the bank was recourse to the railroad, but not vice-versa. The bank could issue debt equal to twice its capital, and expenditures could be thrice its capital. This, for those financially illiterate, is a bit aggressive (sarcastic). The bank was a capital formation machine with little except enthusiasm or politics to sustain its debt repayments or stock price.

North Carolina approved the package, and Hayne convinced the state of Tennessee to do the same. The bank was created in 1836 and authorized to go forward. Kentucky declined, the measure lost by six votes.

Stocks sales increased, to the point that surveys, acquisition and purchases were made, and construction officially commenced. At this point, another financial maneuver, prompted the SCC&RR and the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston to merge, providing sufficient assets to activate the Southwestern Railroad Bank. The addition of SCC&RR meant that operating revenues and the SCC&RR’s ongoing expansion program could generate further enthusiasm to sell stock, and pacify investors while the Cincinnati line slowly began to climb every mountain between Charleston and Cincinnati. The Bank would raise funds begin operations in November 1838.

In the meantime, the Panic of 1837 hit. The price of cotton fell 25% between February and March of 1837, and then things got really bad.

By 1839 it was still declining and called the “cotton crisis”. The Southwestern Bank was not affected (it had begun operations after the Panic started), but when operational, it attempted to raise capital amid a depression environment, without much success.

In March 1839 Hayne died; in 1840 and several times afterward, the railroad was restructured. Out-of-state investors demanded refunds; Tennessee and North Carolina wanted out of the corporation, and got a refund in 1843.

The first effort to copy “Copy New York railroad strategy” had failed.

So SCC&RR was total avoid-default and bankruptcy mode. It needed more revenues to pay its bills and so it pressed on with the internal South Carolina expansion. The Columbia route was completed, with some difficulty, only in 1842. The SCC&RR made it through the Panic, without default, but cost minimization, and South Carolina revenue production were key to its survival. Restructuring meant trying to preserve the assets and operations of SCC&RR, rather than multi-state construction. The financial disarray continued through 1849, limiting railroad expansion not only into other states, but within South Carolina as well.

The South Carolina legislature did not pull the plug, but also did little to keep the railroad afloat. Perhaps the greatest humiliation was that the Hamburg line, to survive, needed to cross the Savannah River, and connect to the Georgia startup (which BTW was having its own problems). To compound matters, the Charleston City Council refused to authorize the right to lay track to connect the line directly to the cotton wharves in Charleston harbor–that would be a 20th Century drama. Stockholders were not happy or fulfilled, however.

The company [however], after many tribulations … reached a basis of substantial prosperity. The public functions expected of the road by its early promoters, however, were never fully realized: the stimulation of Charleston trade, the increase of Upland prosperity in South Carolina, and the checking of the westward emigration [of people and Cotton Belt] were hardly accomplished [3]

No Light at the End of this Tunnel: the Blue Ridge Railroad

After a decade of tough times, the tough got going yet again. The revamped, merged and reorganized SCC&RR, now the Southern Railway, had survived the Panic and cotton price downturn by an expanding and consolidating its routes, operations, and finances. That offered a sound revenue base, credit record, and railroad expertise that could provide an economic base on which to sustain a new push into the mountains and into the Appalachian hinterlands. A new route, built upon South Carolina’s its established railroad base, near the intersection of SC, NC and Georgia–through the Blue Ridge–seemed promising and once again the dream, the External MED developmental transportation infrastructure strategy, was revived in the early 1850’s. South Carolina once again attempted to be the New York of the South.

The 1850’s for the South as a region were the golden years of developmental railroad infrastructure–and the Cotton Empire expansion. The Compromise of 1850 alerted southerners that northern opposition to slavery’s expansion required a re-energized South and a serious commitment to link the southern agricultural economic base to the North’s.

It was felt at the time, among elements (Stephen Douglas) of the North and South that economic interdependence of the two regions with their complementary economic bases, could be achieved only linked by railroads. This idea in the early 1850’s resulted in the first transcontinental (north to south) Illinois Central Railroad that, by the end of the decade, linked Chicago to New Orleans. The South Carolina project envisioned doing the same into the Appalachians connecting, hopefully, eventually, with the border states and central Midwest.

So the big dream of replicating New York’s interior penetration to the benefit of Charleston and the state was revisited as the good times once again rolled. But sometimes it takes a good threat to generate action. In 1851 Georgia’s Western and Atlantic opened its route to Chattanooga. In 1852, the state legislature, on its initiative, authorized a charter for the Blue Ridge Railroad Company; subsidiaries were chartered in four states. Tennessee promised state funds, a loan to purchase rail, and likewise sums were promised by several counties along the route. The initial line would run from Anderson SC to Knoxville Tennessee.

SCC&RR was a private initiative, converted into a hesitant public-private state charter initiative. That venture, among other factors, required sustainable financial investment to achieve its objectives. The South Carolina investment base was not up to that task, necessitating the SCC&RR’s establishment of yet another awkward state-chartered corporation, the Southwestern Bank, to serve as its financial conduit. It came too late, the Panic hit, and a decade was lost and the SCC&RR converted into a South Carolina railroad system, with few pretensions to attempt a multi-state initiative. A decidedly minimalist, state role (even Charleston, its most intense supporter and its greatest beneficiary had not showered public funds on these endeavors) haunted that earlier initiative.

We have seen in this Mini-Series that state political cultures jelled in such a way as to render a serious public-private venture using the state-chartered corporation an uncomfortable and tension-filled enterprise. As early as 1814 the state legislature had gone on record opposing that EDO-type, and its 1818-1830 canal/road internal improvement strategy used a state agency instead. Railroads were another matter, and the 1826 state chartered corporation for the SCC&RR was a departure from canal era internal improvements.

In 1850, with dreams of being the New York of the South, the governor and state legislature chose to return to its cultural roots and, like Georgia, thrust the state itself into the venture.

This created a bifurcated state developmental transportation infrastructure strategy–the state took the lead in the Blue Ridge venture, leaving an assortment of private and state-chartered railroad corporations to extend and build upon the domestic and coastal railroad system. Private railroad entrepreneurship, however, constructing shorter lines with established connection points was more successful. Towns were especially active in financing what were essentially local endeavors. Charleston invested $400,000 in a successful highway to connect with Wilmington NC, and another $260,000 for a highway to Savannah–along with some state investment as well. Once again, it appears that Charleston merchants and its city council was the principal driver behind the state’s developmental transportation infrastructure strategy.

While the state labored on the Blue Ridge Railroad, this domestic network was greatly enlarged and considerable mileage added. This module concentrates on the the state-led Blue Ridge Railroad.

Inspired by Georgia’s government-owned/constructed Western and Atlantic Railroad, the State choose the EDO-type with which it felt most comfortable, the state Board–an early forerunner to today’s department. The State assumed leadership in internal improvements once again, and opened up its purse strings to provide a meaningful $1 million subscription, guaranteed $1.25 million of the company’s bonds, partnership with Charleston which purchased of over $1 million in company stock as well. The push was definitely on. Private investment was secondary in the Blue Ridge project. Within a year, however, the state legislature had second thoughts and reduced its initial commitment.

View From Inside Stumphouse Tunnel

The plan was to open a line up to Knoxville, from Anderson SC, about 195 miles. The first half of the line went through “exceedingly rough country”, requiring 13 separate tunnels to avoid the incline–one of those tunnels about a mile and a quarter long, through solid granite: the Stumphouse Tunnel. Work was subcontracted to private construction companies, primarily a New York-based firm which reorganized in 1856. They ran the project until 1856 when the legislature realized that the firm had systematically avoided much of the difficult and expensive tunneling and concentrated instead on disjointed elements of the project [4]. Nevertheless, the state hard forked out $700,000 and had little to show for it.

The new construction contract was let to George Collyer and work immediately began on the tunnels and bridges. Engineers estimated future costs at almost $8 million. Over 1200 non-slave workers were subsequently hired. Tunneling on seven tunnels was frustrating, with little to show for it–and exceedingly expensive. South Carolina anted up another $300,000 to meet expenses in 1858–and the state legislature feared a serious canal-era-like boondoggle was in the making. State funding decreased, workers were let go, and progress was minimal. The state’s ability managing private contractors, with seasonal slave labor, continued to be questioned.

After nine years, with the arrival of the war, only thirty-three miles of track were laid, although substantial tunneling had been completed, with 1600′ of the 6,000′ Stumphouse Tunnel dug. With funds exhausted in 1859, the legislature declined further involvement, the work stopped and the project ended in 1861.

In a fit of innovation, the State converted the assets of the Southwestern Railroad Bank, into a state-operated revolving loan fund. The RLF invested in stock purchases (equity investments not really loans) totaling almost $4.5 million. It also guaranteed another nearly $4.7 million in private railway bonds–and a few actual railroad loans as well. That brought the state’s 1850’s direct investment in railroads to $9.5 million. During the same period, municipal South Carolina governments also threw in a little more than $4 million, with Charleston providing the overwhelming bulk [5]. The bulk of that state investment, however, was fund proceeds made in the initial 1835-7 SCC&RR multi-state venture, applied to post 1845 private-state chartered railroad corporations.

By 1860, South Carolina developed nearly 1,000 miles of operating rail, tenth in the nation, but had given up on its dream of being the New York of the South. Charleston accordingly, was heading for darker days, not only because of General Sherman. Phillips summarizes the residue from the Blue Ridge RR’s failure as:

the [Blue Ridge] enterprise was the work of the Charleston interests. The state aid secured was the result of Charleston’s influence, aided by representatives along the route. The disappointment was shared by the merchants of Charleston, the planters of the upper Piedmont, and the farmers of East Tennessee.

the cuts and frills of the forgotten blue Ridge Company are [at time of his writing] studded with well-grown oaks and hickories; and the Stump House tunnel mouths are choked with shrubs. And Charleston still longs in vain for the trade of the golden West [6].

South Carolina Transportation Strategy Wrap Up

The failure of the Blue Ridge Company contributed to what would be a long-standing South Carolina ED-relevant legacy. The Smokehouse Tunnel was from its start seen by many as a futile enterprise, and its nearly decade long track record a stain on ED’s track record–a boondoggle of the first order.

Still, there was considerable distrust of state-chartered corporations which to many perceived to be vehicles for financing elite profits and politician’s maneuverings. Outside of the Charleston business community, few could discern how all this would benefit their sub-region, or themselves personally. Lacy asserts an old 1850’s South Carolina expression “Old Fogyism” “represented opposition to railroad construction, or to economic development in general“. He believes this common man critique tapped into “fear of the unknown, and a general indictment “of the future“–say it another way–“cling [ing] stubbornly to tradition … and an “instinctual distrust of anything new and different … [a previous] obstacle to economic development in the [Scots-Irish] Upcountry” [7].

Triggered by the Panic of 1837, this republicanism was revitalized and initially took shape in its opposition to state-chartered corporations. Typified by the words of Governor Patrick Noble, a close Upcountry friend, law partner, and ally of Calhoun, “denounced [message to the 1839 legislature] corporate charters with pure Jacksonian venom as instruments which ‘confer exclusive privileges on certain persons, and intrench [i.e. impinge] upon the equal rights of the rest of the community’ [8]. The Blue Ridge ED initiative, and its obvious failure provided sustenance to this “gut tendency” of the Scots-Irish political culture.

When, in the early 1850’s, with some of the pain associated with the Panic worn away, a muted Whig hope in material progress, a fear that without a viable western railroad expansion it would be threatened, and willing to use government to achieve it was exuberantly asserted in the good times of the 1850’s by the Deep South planter class, in conjunction with the more intense adherence by urban Charleston business community. It was not equally shared by Scots-Irish, and would become a Deborah Stone-ish “story”that would continue into future South Carolina ED-relevant policy-making. As Lacy would argue:

Projects designed to promote economic development met rooted indifference more often than orchestrated hostility. The Blue Ridge Railroad Company was hindered throughout its existence by a general indifference to the project outside of the Charleston commercial community [9].

Lacy asserts that while some opposition to it can be attributed to the planter fear of threatening the primacy of Cotton Empire and the South’s agricultural economic base, most of the opposition (from both political cultures) “was animated by the familiar republican fear of higher taxes, and growing government indebtedness” preferring instead it be built with private capital. The brief Whiggish–Charleston merchant-inspired tilt that motivated the early 1850’s state leadership in External MED produced a mixed cultural reaction in South Carolina which, if Lacy is correct, tapped more than the Deep South-Scots-Irish discomfort with privately-led public-private projects, but also ran afoul of its low taxes and limited view of government–the fundamental pillars of what would prove to be the predominant southern business climate.

If so, South Carolina was already “of two minds about economic development” in the 1850’s–before the Civil War and the existence of “post-Reconstruction Redeemers”. Here I draw a distinction implied but not made by Lacy Ford. Upcountry (mostly Scots-Irish) retained “lingering Jeffersonian misgivings [what he calls republicanism] “about expanding commercial involvement, and especially about using state government as an agent to promote economic development” [10].

Footnotes

[1] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, p. 104)

[2] The SCC&RR 1835-1842 tale is drawn eclectically from Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890 and Phillips, History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860. Both overlap and while each may include additional materials, together they agree on the key events of this period–and they share a similar view of its issues and problems. Supplemental research was also consulted to verify inconsistencies and reconcile timing.

[3] Phillips, History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860, p. 220.

[4] Aaron Marrs, Railroads in the Old South: Pursuing Progress in a Slave Society (2009), pp. 50-4

[5] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, pp. 105-7

[6] Phillips, History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860, p. 380.

[7] Lacy Ford, Jr, Origins of Southern Radicalism: South Carolina Upcountry 1800-1860, pp. 316-20.

[8] Lacy Ford, Jr, Origins of Southern Radicalism: South Carolina Upcountry 1800-1860, pp. 314-5.

[9] Lacy Ford, Jr, Origins of Southern Radicalism: South Carolina Upcountry 1800-1860, p. 318

[10] Lacy Ford, Jr, Origins of Southern Radicalism: South Carolina Upcountry 1800-1860 ,p. 314.