Georgia, Atlanta and the Western and Atlantic Railroad

Virginia and Georgia were the most successful southern states in the antebellum/ Early Republic railroad age. In contrast to South Carolina, where I argued the interplay between the Barbadian Deep South and Scots-Irish political cultures, had created an atmosphere and policy system if not opposed to meaningful public-private ventures that used state-chartered privately-run corporations, preferring instead that the state “do it itself” through a series of state EDOs, the state of Georgia took a slightly different path.

The Georgian political culture blended Virginia Tidewater, South Carolina Barbadian, and Scots-Irish elements in a complex sub-regional pattern that permitted a Whiggish planter maverick to become governor who set in motion legislation, and created a workable bureaucratic structure to build the most risky part of a combination public/private state-wide railroad transportation system that centered on a hub and ran into the Appalachians using a route with the best prospects for success. The hub, in an mostly unsettled, unpopulated area, outside the Cotton Belt and the state’s non-cotton agricultural North, without any conscious state planning or material resources, grew into a city: Atlanta.

This module contents itself with exploring the “railroad-developmental infrastructure” context that affected its decision to embrace state leadership in that strategy. Similarly, this module “introduces” Atlanta to the reader, by concentrating of its “railroad” induced birth, in an undeveloped, almost marginalized location in Georgia–a location that proved to be a favorable to a rail nexus-hub. Atlanta will be tacked in greater detail in a Theme 3 later module, and will be a continued example throughout this Online History. In this case, we focus on an urban birth in which the railroad was considerably more than a midwife, and actually was a proud parent.

The parent who “birthed” this new hub-city, was the Western and Atlantic Railroad–a state-owned rail line (W&A). This module completes Theme 3’s Mini-Series on the South’s External MED developmental transportation infrastructure strategy by concluding with a brief case study of the W&A.

The study is helpful, not only because of its description of Atlanta’s “birth”, but because, in the opening words of Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, “it was the perfecting member in a well-devised railway system which made Georgia the keystone state in the South … and it furnishes the most important example in American history thus far, of the state ownership and operation of railroads” [1].

Carter Goodrich concurs:

the Western and Atlantic Railroad …. like New York’s Erie Canal … was an enterprise of state government; and it bore a unique and planned relationship to the other internal improvements of the state, which were mainly the work of private individuals and city governments [2]

Goodrich’s observation points out a critically important factor in W&A’s success. Georgia state did not build railroads as a system. Rather, it built the one railroad that tied together a system that was being developed by private entrepreneurs, using municipal and some state level public funding. The publicly- funded and constructed central trunk that unified the disparate private projects–the hardest and most expensive one. Georgia state government had deep pockets and sustained its commitment long enough to complete the task (1851). That it took until 1851 to complete is testimony the initiaitve was never a sure thing. Finally, we see an early example of state inclusion of the External MED strategy to city/county governments and private enterprise. Pennsylvania also mirrored this approach.

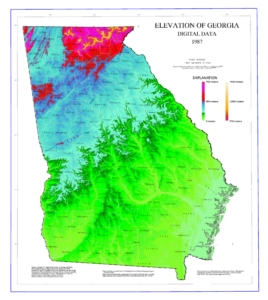

As to topography, Goodrich states “In Georgia the mountains were lower, as the Appalachian Barrier approached its end, they presented a less formidable barrier to transportation [3]. That topography didn’t doom the endeavor/strategy to inevitable failure as it did South Carolina, is simply that Georgia routed through the fledgling settlement of Chattanooga, instead of tunneling through sheer granite mountains to Knoxville. Knoxville, ironically, made its commitment in 1855 to a branch line tied into Chattanooga.

Chattanooga, like Atlanta, was created by its hub role; that city served as a nexus for deeper access into the South–and like the Illinois Central which was being constructed at this time, would extend ties into the North, linking the two competing economic and political systems, into a more harmonious whole.

the Georgia “Railroad” Context

South Carolina’s post-1835 privately-led trans-mountain venture had successfully forged a seemingly impossible, viable multi-state alliance to create New York-like access to hopefully open up much of the South’s central interior, making in the process, Charleston the New York City of the South ( that New Orleans would have a say in this is obvious, but beside this point). What frustrated that multi-state alliance was the (1) the Panic, and (2) topography–crossing the Appalachians from South Carolina was probably beyond the technical capacity of railroads at that time, and certainly (3) exceeded South Carolina’s ability to generate funds sufficient to that purpose. The death of its key entrepreneur was the final nail in that coffin. The Blue Ridge Railroad, was at best an “uphill climb” through a granite wall.

The State of Georgia, on the other hand, was always a player in developmental transportation infrastructure, albeit less noticed in the 1830’s–as was Virginia. Georgia constructed a wagon road to the Tennessee border, through Cherokee country in 1804-5. During the “internal improvements” phase, the state of Georgia authorized several turnpike companies (through stock purchase), although none were successfully launched.

Unlike South Carolina which had to be dragged into infrastructure projects, Georgia more willingly partnered with municipal governments in river improvements, not at all common during the Early Republic period. In 1817, as did South Carolina, Georgia embarked on a major “internal improvements” strategy, including substantial river improvements. Central to that strategy, was establishing (1817) a permanent Internal Improvement Fund, initially funded at $250,000, later increased to $500,000, that could be accessed by municipal and private projects.

In 1826, later than both Virginia and even South Carolina, Georgia created a Board of Public Works. The 1827 Report of this Board (and its State Engineer) advocated railroads, not canals, as Georgia’s preferred mode of transportation. The Report included a detailed and accurate summary of Georgia transportation realities, and called for a ‘state system of transportation’ that resisted the seduction of “siren magic of distant trade” (i.e. the multi-state Erie Canal opening of the Midwest) and on the other hand to avoid “uncoordinated local efforts” [4].

What a great start!

Oh well …. the Board closed down a year later.

Uncoordinated local efforts became the norm for the next decade and a half. Savannah, Georgia’s largest city (a small coastal port), funded canals, and a ton of river improvements. Often the state dutifully participated in its infrastructure projects. Because it was not a central export port like Charleston, Savannah’s business community, smaller and less cosmopolitan, was domestically-oriented, and reacted more intensely to the goings-on of rivals.

In 1833, two significant private-led and funded railroad state-charter corporations were approved–and Georgia entered into the Age of Railroads. The first, the Georgia Railroad, in the state’s interior (Augusta), was triggered by the SCC&RR’s Hamburg–Charleston line. The Georgia Railroad connected Augusta to the Savannah River, and stood poised to link with other regions. The second railroad, the Central of Georgia Railroad, connected Savannah to Macon. Both were essentially local lines, financed with private investment, supplemented with municipal/county level funds and relatively minimum state assistance. Both projects linked into the Savannah River and Savannah. The Panic hit midstream, delaying both railroads from opening until 1841, and 1843 respectively. Georgia initially cooperated in the SCC&RR’s multi-state venture, approving a Georgia version of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston banking subsidiary, Southwestern Corporation, for example.

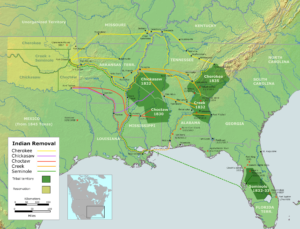

Before the Panic hit, Georgia was, like South Carolina, tempted to devise its own path into the Appalachians (despite the warning of its deceased Bureau of Public Works). Much of the area through which W&A would transverse was former Cherokee lands. With the removal of its Indian tribal populations in the early 1830’s, many sensed the time to act was now. At this propitious time, a Whiggish-Democratic governor, Wilson Lumpkin, seized the initiative.

Lumpkin, the 1836 Macon Railroad Convention, and Terminus

In 1831 (to 1836) former Congressman Wilson Lumpkin served two terms as governor. A planter, of English origin, born in Virginia, he presided over the more significant phases of Georgia’s Indian Removal, which he described as his “particular mission” (the Cherokee Trail of Tears began in White County, Georgia–4,000 Cherokees perished). Judging by subsequent facets of his future career, it appears Lumpkin, a Democrat, displayed Whiggish tendencies. instead

He supported the tariff, and deeply opposed Calhoun’s nullification–in fact was reelected on that platform in 1833. He later served on the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Manufacturers, was appointed to the Georgia State Board of Public Works, and, played an aggressive role (General Manager of the W&A) in the decision and implementation of the Western and Atlantic–the core subject of this module. Evidently, he also was deeply involved in the birth of Atlanta, which BTW voted to name itself after him (Lumpkin); at the Governor’s request, instead named it (Marthasville) for his daughter. In Atlanta’s case, as we shall discover, the fifth name is the charm.

The South Carolina Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston project activated Georgian railroad enthusiasts, including Lumpkin. Lumpkin earlier in his life, investigated a route that could open up the Appalachians, and, while engaged in his “particular mission”, received overtures from South Carolina and others (Memphis and Charleston RR), motivating him to dust off his earlier ruminations. His initial intent was to challenge Charleston as the South’s chief Atlantic port by positioning Savannah as realistic alternative.

On 1833, two Georgia private railroad startups (the Georgia RR, and the Central of Georgia RR) provided opportunities and allies. While actual construction was slow, these two railroads strongly advocated in the state legislature for new railroad construction so to create a larger, unified “state transportation system”. Officials/owners from these two railroads got themselves elected as state representatives and after 1833 became an active force in support of railroad development. hey proved to be the cutting edge for the W&A state initiative.

Lumpkin watching off to the side, submitted legislation (1834), which was approved, endorsing “a scheme of internal improvements from the seaboard of this state to the interior by railroad, on the faith and credit of the State, as a great State work [5]. With no identified specific project in mind, the State committed itself to finance and construct a major railroad project. 1835 came and went, but matters came to a head in 1836 when the earlier-described Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston 1836 Knoxville Convention forced a decision to join the Charleston initiative, or counter with its own project.

the Western and Atlantic Initiative

Georgian representatives at the July (1836) Knoxville Convention, had formed a caucus, drafted a proposal that required the Louisville-Charleston project to also build a line to Savannah, and brought it to an unsuccessful vote. Defeated, they failed to support the Charleston-based project. In November (1836) with Governor Lumpkin’s support, these railroad advocates held their own convention in Macon (107 delegates and 38 counties). They determined to go forward with their own line.

Their report called for a Georgia route into the Appalachians–to the Mississippi Valley ultimately–and made reference to the opportunities that flowed from the Erie Canal, and the threats by Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and now South Carolina to “open up the Midwest”, leaving Georgia in the dust. Importantly, the report advocated the state endorse a 130 mile single truck line, which not only opened up into Tennessee, crossing into the Appalachians, but linked the two aforementioned startup railroads to a terminus point/hub. From the hub a Tennessee-bound trunk line (the Western and Atlantic) would start its run into the Appalachians to Chattanooga.

Prodded by Lumpkin the Report was drafted into a legislative proposal, endorsed by the Governor, and aggressively pushed by the railroad’s elected state legislators. Significant opposition appeared (based largely on many of the Lacy Ford’s “republican’ concerns), but due to intense log-rolling with other pork and internal improvements, went to a narrow victory in December, 1836 [6].

The legislation required a survey to draw a route to Tennessee that would be anchored at a terminus/hub, The survey specified the terminus should be in a largely unsettled, economically marginal central Georgia, somewhere across the Chattahoochee River. The legislation authorized the State to begin construction, appropriating $350,000 per year until future state legislation altered that commitment. A superintendent and engineer, appointed by the legislature, was to manage the project. Additional state subscriptions (stock purchases) were authorized to assist other branch railroads–log-rolling–tying them into W&A’s trunk line ($200,000 per year, per railroad).

Without plan, and probably intention, the Governor and Legislature had devised, ad hoc, a railroad transportation system that linked Savannah, first to key points/cities within the state, connected them to a terminus-hub that accessed Chattanooga, and from there to (as yet unbuilt) lines in central and southern Midwest.

In 1836, the legislature authorized sale of $1.5 million in state bonds and in 1837, approved a governance commission (including the Governor), and precisely specified the terminus be eight miles southeast of the Chattahoochee. Funds from the Central Bank, a virtual subsidiary of the State initially created by the State in 1828, were made available, and the bank converted into a financial conduit for these transactions, rendering much of the financing off-budget. Effectively, both the W&A and its financial conduit the Central Bank, were isolated from politics and the legislature, annually financed by state funds without need of annual appropriation, and to construct a line within those financial parameters without undue interference. Then as the reader no doubt anticipates, the Panic of 1837 hit.

But bonds had already been issued, the Bank was in operation, and prescribed annual state funds continued. The Panic did not impede construction until 1839-40. The principal effects of the Panic were that FDI, sought after by the State, did not happen, and budget limitations slowed construction significantly. Contractors accepted state script as payment in the interim to solve cash flow problems. Only in the spring of 1842, was construction suspended. This proved of little consequence because it gave the branch railroads time to complete their projects.

The legislature reauthorized construction funding after connection at the terminus point was made by branch railroads (1845-6). During this time an active opposition nearly torpedoed the entire package–Lumpkin was in the U.S. Senate, and the W&A Commission was disbanded, but the project itself was still managed by a state superintendent. When a major obstacle to Chattanooga was removed (the Tunnel Hill tunneling) was accomplished in 1849, funding resumed, and the route to Chattanooga sped to its final completion. The first train rolled into Chattanooga in May 1851.

All of which brings us to our final topic in this module: the terminus point in central Georgia.

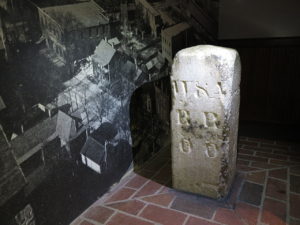

The original Zero Milepost: Atlanta

The initial prognosis for the unsettled area around the terminal point was dismal indeed. David Goldfield reports that at initially Atlanta’s location was deemed unsuitable by contemporary commentators:

The unsuitability of Atlanta’s hinterland for staple cultivation was … an indication of a dismal future …’the place can never be much of a trading city … [and would be] a good place for one tavern, a blacksmith’s shop, a grocery store, and nothing else” [7]

The 1836 legislation, left the terminus point, on the margins of the Cotton Belt, undefined. The survey authorized by the legislation specifically determined the terminus using engineering and topography criteria, placing it eight miles from the River–and literally drove a stake in the ground to mark the spot. A zero milepost was later added.

In 1839, a certain John Thrasher was hired to oversee construction around the terminus point. He built a general store and homes for his laborers–the first land development in what the railroad called Terminus. Thrasher gave it his own name, “Thrasherville”. He purchased on his own initiative additional land for future development. When the railroad got a land donation (1842), it shifted the terminus from the Zero Marker–moving it four blocks away from Thrasher’s fledgling speculative development. The “settlement” at that time was six buildings and thirty residents. Thrasher was mad, sold his land at a significant loss, and moved away [8].

So Thrasherville was no more, and the railroad’s name “Terminus” was reapplied. That apparently displeased the thirty residents who voted to name the place Lumpkinville, a honor declined by the former Governor, who requested they name it after his daughter. So the name changed from Terminus to Lumpkin, to Marthasville. By that time (1846), Atlanta was the hub for three branch railroads (and a fourth on the way)–but not one railroad locomotive had yet reached the metropolis.

In the meantime, Thrasher regretted his impulsive decision and returned to Terminus in 1844. Opening up a grocery store once again (on today’s Peachtree Street). Elected to the Fulton County legislature, making a close friendship with Mayor, Jonathan Norcross in the process. Norcross was the first manufacturer to set up business in Atlanta, a saw mill in 1844.

When the first branch railroad (the Georgia Railroad) formally connected to Marthasville, its owner urged a name change to “Atlantica-Pacifica” in what proved to be the last of crazy inappropriate names given to poor old Terminus. In 1846, the second railroad connected Marthasville, linking whatever-the-place-was-called to Savannah and Macon. Atlantica-Pacifica, predictably, was shortened, and in 1847 “Atlanta” was incorporated as a city, with a population around 2,500.

In 1848, the city had its first murder, and so duly elected its first mayor, appointed its first town marshal, and built its first jail. Atlanta was off to a roaring start–in fact a land and population boom soon followed.

The W&A opened for business in 1851; , Fulton County was created in 1853 , and in 1854, a fourth rail line accessed the hub. By 1855, with a population of less than 7,000, Atlanta was already the South’s premier railroad hub.

By 1856 Norcross was also the owner of a railroad under construction (Richmond-Danville Railroad) which would open up much of northern Georgia. Thrasher and Norcross endured the 1864 burning of their city by Sherman (or Hood, depending on who you believe). Norcross went on to be elected, postwar, the fourth mayor of Atlanta. The city’s population was reduced to about 3,000–even Thrasher left (again), his home taken over as HQ by Confederate General Hood. Taken over by the Federals, it was looted, not burned, but converted into a blacksmith operation. Sometime in 1865, he returned to his city, and in 1866 he was one of twelve charter members for the Atlanta Street Railway Company which was duly chartered to construct and operate Atlanta’s first streetcar line.

Delayed by the Civil War, and impeded by its destruction, the Norcross rail line did not open until 1869. At which point Thrasher bought the land surrounding its terminus, repeated his earlier land development and speculation antics, and in effect, founded the city of Norcross GA (a thriving Atlanta suburb of nearly 10,000 today).

Whatever prompted it, Thrasher left Atlanta-Norcross sometime in the 1880’s–leaving for of all places, the largely unsettled Florida southern coast. He, his wife and family, settled in Dade Florida (near Tampa Bay), and planted, believe it or not, orange trees. In 1887, his son was elected a county judge. Thrasher wasted little time and by 1885 was pitching support for a new railroad that was knocking on Dade’s door’s. The Florida Southern Railroad was built, soon purchased by a northern investor. In 1887 Thrasher returned to Atlanta, speaking at its Piedmont Exhibition, sharing the podium with President Grover Cleveland. He died in 1899, and his descendants were founders of Coca Cola, an outstanding Georgian philanthropist (Caroline Thrasher), and a recent Governor.

Footnotes

[1] Phillips, History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860, p. 303.

[2] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, p. 115.

[3] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, p. 115.

[4] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, p. 116.

[5] Goodrich, Government Promotion of American Canals and Railroads, 1800-1890, p. 117.

[6] Phillips, History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860, pp. 308-11.

[7]David R. Goldfield, Cotton Fields and Skyscrapers (1982), p.35

[8] Whether or not Thrasher “founded” Atlanta is a bit of an exaggeration, Norcorss also played a significant role, but he clearly was a southern city-builder who specialized in railroad termini.