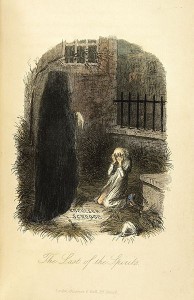

The Ghost of Christmas Present: Ok, It’s Not True But Is There a Truism That Is True?

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

The first article in our Tolkien-like small business trilogy asks (asked) the question if , as claimed in the Economic Development truism, “small business is the nation’s best and greatest job creator” is actually true and literally correct. A related question that follows from the Truism is: “Are start ups the best, most dynamic job creators among small business” is also under question.

The orgin of the Truism has been traced to Dr. David Birch, who in a series of publications over the 1979-1987 period, published research “proving” that small business was the nation’s best job creator and that 80% of all new jobs created were by small firms. Birch’s original path-breaking answer to both questions was small, under twenty employee firms. SBA, governments, politicians, academics and just about everybody else on the planet leaped on board and now twenty-five years later the truism is gospel and everybody acts as if the Truism is, in fact true, and correct.

Size of the firm is the critical variable responsible for job positive net creation; smaller firms hold almost magical powers to create jobs and start ups are, by definition, small firms.

But in the Ghost of Christmas Present we asked the question: Is the Truism true?

A Truism in Search of Truth

Well, it turns out (and you would know this if you read the Ghost of Christmas Past) that almost immediately upon publication, Birch’s research, and particularly his methodology, was questioned in VERY FUNDAMENTAL WAYS. By the middle 1990’s, a second series of articles by Davis, et al (and others as well), cited several significant concerns regarding Birch’s approach and findings, the worst of which was something called the regression fallacy. The essence behind the fallacy was that Birch’s numbers did not support Birch’s claims that small business was the greatest job creator. Davis not only severely critiqued Birch’s methodology, but made adjustment and redid his work. Davis’s research discovered that small business did NOT really create jobs– anywhere near the rate Birch had claimed, and that, o horrors of horrors, large firms created jobs as well. The Ghost of Christmas Present had arrived and, in the world of academics and economists, Birch was on the defensive.

Not very surprisingly, yet another set of economists reviewed Davis’s articles, concluding that he may have been right about Birch’s methodology being faulty and his findings overstated, but also savaging Davis’s counter research which was based almost exclusively on the manufacturing sector which was, as well all know, losing jobs in a period of deindustrialization. Academics could not arrive at a definitive answer to our two initial questions and in the vacuum, the SBA, media, politicans and economic developers stepped into the vacuum and the Truism became True. Fess up, you, the reader, still believe the Truism today.

Well, you shouldn’t. As we discussed in our first review (Christmas Past). a 2009 article by Neumark et al, published by NBER, updated the critiques of Birch and Davis and finally redid Birch’s research. Neumark et al came to the conclusion that both the very smallest of small businesses, less than twenty employees, as well as large firms, greater than 1000 employees, do create the most jobs, but at a rate less than 3% annually. Not exactly a barn burner compared to Birch’s original statement that 66% of all new jobs (1969-1976) were created by firms less than twenty employees.

In short, Neumark’s research suggested the truism was to some degree true, and false. But, as far as solving any current unemployment problems, the Truism seemed to offer humbug, hohum opportunities? Worse, Neumark and others, now including Birch himself, questioned the importance of size of firm as the critical variable in job creation. Small size alone did not appear in itself to be all that important in job creation. Several competing approaches cropped up in the literature and think tanks. How each of these competing concepts were different to, or related to, each other was at best obscure. The original Truism, however, offered simplicity and clarity that even a newspaper reporter could understand. The Truism continued to acquire even greater acceptance, despite the uncomfortable, behind the curtain reality that the core observations of the Truism were under serious attack and we evolving into a new Truism which was quite different from the original Birch Truism.

Speaking of Birch, Birch himself (1994) abandoned size. Instead Birch proposed that firms possessing a certain “character”, high revenue growth, which he labeled “gazelles” created the most jobs ( not the slow growing “elephants” or” mice”. Gazelles were the critical dynamic force behind net new job creation in the American economy. There did seem to be a “size” component still remaining in Birch’s gazelles vs. elephants vs mice, but it seemed secondary to a sub-class of fast revenue-growing firms which were really creating the net new jobs.

Neumark and others (as you will see in this review), however, picked up another thread in the job creation argument: the age of a firm. Age was a complicating factor because many researchers asserted that the more mature firms created net new jobs at rates superior to young (and presumably) small firms. In fact the big job creating firms could be any size and what was really important was that we better understand those firms regardless of their size or even age. By the middle of the last decade, research behind the Truism’s fundamentals was in evolution.

Our task in the review of Christmas Present is to pick up the pieces of the cracked Truism, return to the original questions as to which firms create the most jobs, and then in our third review concentrate on how we as economic developers try to help them do it We shall present below two articles. One posits that age of firms is the most critical variable in job creation. The age-focused small business perspective concludes that the young and restless firms are the best job creators and that start ups are especially critical to net new job creation in the American economy. The second article moves the reader away from age to what we call “character”, in this case high-impact performance in revenues and job creation. Those firms which are high-impact create the disproportionately most net new jobs, regardless of their size or age. In fact, the article will allege that more mature firms exhibit the “highest rates”, i.e. disproportionate share of net, new job creation? Which should we believe? We will eventually argue both should be believed–but that gives away our surprising ending.

The surprising ending comes from the Kauffman Foundation and the article we selected from their arsenal puts job creation in a larger context. The Kauffman folk explain the overall “structure” of the long-standing American job-creating process and dynamic. They advance what they call a “neutralist” explanation of how age, size and high performance are linked. Kauffnan Foundation asserts a kind of macro-economic perspective into our heretofore micro-economic focus. In their persepective one wonders if size, age and high impact are all somehow dependent, not independent variables of the American “way” to create jobs.

As we shall discover, each of these studies relies on their own specially constructed databases. Databases have evolved significantly from the times of Birch and they are key to our understanding that as the quality and the duration (how many years the database includes) of a database improves, new databases permit us to penetrate deeper into dynamics which, for the most part, were really hidden from Birch. This issue exposes a really, really (did the Curmudgeon say, really, really?) important lesson for all economic developers: methodologies, indices, and database integrity matter. We shall, to the reader’s considerable discomfort, place a focus on methodological issues, but promise to try to do so in terms even Scrooge could understand. There is nothing fancy about the Curmudgeon and “simple is as simple does” (Forrest Gump to those who are movie challenged).

That the Small Business Truism survives and prospers is because economic developers, media, and everybody won’t take the time to understand that ALL answers to the question of “who creates the jobs” is in essence a methodologically-dependent enterprise. Different methodologies and definitions will yield somewhat different answers And to compound our misery, we need to distinguish between several questions which in today’s world seem to have been inappropriately jumbled up into one question. We must understand which ONE question we are asking before we can evaluate the research findings. Are we asking who creates the MOST new net jobs absolutely? Or are we asking which segment of firm’s disproportionately create net new jobs at rates higher than other segments? In any case, we shall deal with these methodological issues in English, not math. but we should really understand the consequences of different methodologies and indicators; methodologies and definitions can create meaning and misunderstanding.

Many economic developers (and the politicans for whom they work) , the Curmudgeon believes, have not really grasped these methodological distinctions and instead have steadfastly adhered to the incorrect, or at best imprecise, original Birch-inspired small business Truism. That the Small Business Truism survives and prospers because economic developers, media, and everybody won’t take the time to understand that ALL answers to the question of “who creates the jobs” is in essence a methodologically-dependent enterprise. Different methodologies and definitions will yield somewhat different answers. The Truth in Truisms can sometimes be hard to find.

John Haltiwanger (Univ of Maryland, NBER), Ron S. Jarmin (Census Bureau), and Javier Miranda (Census Bureau) “Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young”, August 2011 (Haltiwanger)

Haltiwanger: Core Findings

Haltiwanger et al’s basic finding is very straightforward: “we find an inverse relationship between net job growth rates and firm size, (i.e. the larger the firm size, the lower the rate of net job growth), although we find this relationship is quite sensitive to regression to the mean effects” [if you had read Ghost of Christmas Past review, we called this the regression fallacy and it means that the number of jobs that is allegedly created is artificially exaggerated–this is not good]. “Second, once we add controls for firm’s age [how old is the firm], we find no systematic relationship between net growth rates and firm size” (p. 2) [in other words, age of the firm, not size of the firm, is the key independent variable].

“…because new firms tend to be small, the finding of a systematic inverse relationship between firm size and net growth rates … is entirely attributable to most new firms being classified in small size classes.”

If this finding is correct, then Birch’s pre-1994 Truism is bye bye. Small, less than twenty employee firms are NOT the best generator of new net jobs. YOUNG firms are the best! In theory that means young, big firms can exhibit high net job growth rates as well as young, small firms. Yet, even simple straightforward observations have a way of getting complicated in economic research. Haltiwanger further observes, however, that there is a rather sleazy relationship between firm age and firm size. Calling attention to a phenomena he labels “firm births” [most of us call it start ups], Haltiwanger finds “that firm births contribute substantially to both gross and net job creation. Importantly, because new firms tend to be small, the finding of a systematic inverse relationship between firm size and net growth rates … is entirely attributable to most new firms being classified in small size classes.” (p.2)

In alerting us to this subtle distinction, Haltiwanger et al shift our focus away from small firms, or even young firms, toward start up firms. So if you as an economic developer like to work with start up firms, then Haltiwanger is the guy/researcher for you. He furthers suggests that if the young firm survives at all [i.e. it doesn’t die} that “young firms grow more rapidly than their more mature counterparts.

However, young firms have a much higher likelihood of exit [i.e. die] so that job destruction from exit [death of firm] is also disproportionately high among young firms” (p. 3). Say it another way, a lot of start ups create a lot of jobs and then they die. Anybody working with start up knows this phenomena first hand; we didn’t need Haltiwanger to crunch numbers for that one. Nevertheless, Haltiwanger does provide the support for asserting that larger more mature firms (he calls them continuing firms) have less job destruction rates than smaller and younger firms. If economic developers are determined to work with smaller firms, be prepared for higher “exit” rates and for greater volatility in your job counts. Instead of being a strategy of huge job growth, small business development may be more like riding a roller coaster–start up and end at essentially the same place, but the ride sure was a lot of fun.

Instead of being a strategy of huge job growth, small business development may be more like riding a roller coaster–start up and end at the same place, but the ride sure was a lot of fun

Still, small mature [i.e. older] firms make poor prospects for economic developers. They may be more stable, or less volatile, but they have “negative net job creation” (p. 3). [These last two findings suggest to the Curmudgeon a rather no win situation for an economic developer. Either she works with young, small firms and see lots of early year net job creations and then watch these firms die, swallowing up all your time and money and depressing your job counts; or, you work with stable, mature older small firms and watch them disintegrate job by job, year to year]

All these findings would not have been possible if Haltiwanger had not developed what all other small business researchers constructed: their own particular database. Birch had his, Davis et al had theirs, Neumark et al had theirs, and now Haltiwanger et al have theirs. All of the studies we have reviewed in our last issue and this issue, have their own special database. There is no common, shared database.

Haltiwanger: Database and Methodology

Anyway, Haltiwanger’s database was developed by the Census Bureau, their Census Bureau Business Dynamics Statistics (BDS) and its Longitudinal Business Database (LBD). This database is held to be especially sensitive to firm births and deaths. The LDS and its derivative BDS is based on establishments and by its very nature penetrates into firm dynamics (birth, death, job creation, age) more clearly than a database based on firms. [The reader is urged to read our Ghost of Christmas Past review if uncertain regarding the distinction between firm and establishment]. A database of establishments can allegedly account for the effects of mergers, acquisitions for instance, but establishment level data can make assessment of firm size or even age more difficult [they cite for instance that job growth in retail sector usually means more establishments-not growing jobs at a single establishment].

To really get at job growth at the firm level and to penetrate internal firm dynamics, a research really needs a database of both firm and establishments and there is none to be had for all sectors and industries except Neumark’s NETS data [see Ghost of Christmas Past]. LBD, however, does offer some compensatory benefits associated with its time series and its “within year linkages of establishments to their parent firms” (p. 7).

The LBD covers all “establishments” with at least one paid employee in the United States. The data series begins in 1976 and at time of writing included thirty years of data for industry (SIC). The data utilized in Haltiwanger’s article draws from the 2002-2005 period. Firms can be aggregated from the establishment data and both a pure base year and average size variable were computed. Firm age, birth and death are also computed

Since we make pretenses to providing information and frankly adding to the reader’s knowledge-base, we feel compelled to dig into the muck of methodology for a short while. In Ghost of Christmas Past we spent some time talking about the chief methodological concern with Birch was the “regression fallacy” or what others call “regression to the mean”. What this boils down to in the Curmudgeon’s warped mind is the following. It seems so commonsensical; all one has to do is count the jobs in Year 1 for a firm, then count the jobs in Year 2, and you have what you need. But numbers are not necessarily what the numbers are. In this case, Year 1 is called “base year” and it is the critical issue. If base year is wrong or atypical, than net growth is also wrong or misleading.

No matter what base year you choose there is no real way to determine if the job count for that year is an aberration, a mistake, a transition from a temporary situation, or the real thing? Neumark’s article in the Ghost of Christmas Past and now Haltiwanger “solve” this regression fallacy by compiling an “average size” of several years employment in each firm. It will not be enough for a firm to be classified as “under twenty employees” if that firm only has under twenty employees for one year only and then grows. For Haltiwanger the firm must be under twenty employees for three years.

To compound our misery the quality of the data, and the distinction between firm and establishment further confound this issue immensely. As to quality of the data, the reader should keep in mind one is counting, in theory, every firm in the nation, in all sectors and industries. The issue of actually counting new firms, i.e. start ups is a potentially hit or miss enterprise. Data entry alone can create lots of opportunities for all sorts of stuff to creep into the database. It all accumulates and base year errors or atypical base years may be more common than we would like to admit. Birch arbitrarily chose a base year and used a somewhat tainted, bad reputation D&B database. Properly-trained methodologists are now going “harrumph”, but the quality of the data base and the definitions of variables are critical to any answer to our question at hand. Ignore those issues at your peril.

The issue of gross jobs (which do not include job destruction) and net jobs (jobs created minus jobs destroyed) is frequently confused, especially in the media and even the economic development literature (which, admit it, can be self-serving). Small business in any one year can create a lot of jobs, but the next year they may all be in the unemployment line. In fact a firm which is born and dies in the same year is not counted at all.

Haltiwanger points out what we really want to know is “whether any identifiable groups of firms DISPROPORTIONATELY create or destroy jobs”.That does not mean, however, they create THE MOST JOBS. Got it?

When we link ” (high or low) rates” of job creation with the question of “who creates the most jobs” we invite confusing gross with net job creation. The question is improperly phrased and as Haltiwanger observe from their findings that size classifications of “firms that have the most jobs [to begin with, also] create the most jobs” (p. 10) and not surprisingly that is large and mature firms. So the answer to the question who creates “the most jobs” is large and older firms.

But as Haltiwanger points out what we really want to know is “whether any identifiable groups of firms DISPROPORTIONATELY create or destroy jobs” [this means dealing with “rates”] (p.10). That does not mean, however, they create THE MOST JOBS. Got it? The question we are grappling with in this set of articles concerns RATES of net job creation, not necessarily the numerical number of net new jobs created.

Haltiwanger: Putting Some Flesh on the Bone

The effect of averaging size classifications, however, seems to be a “muting” of the rate of net job creation. Small and/or young firms do create a lot of jobs, but job destruction is correspondingly high. Haltiwanger convincingly demonstrates there is a world of difference in one’s findings, depending upon whether one uses base year or average size methodology. As to which is inherently correct, you pays your money, and takes your choice. The Curmudgeon’s dough is on average size. That means, drawing from Haltiwanger, who put his money on younger firms of any size, more than on small firms of any age.

But Haltiwanger also explores what he calls the “up or out” pattern of young firms. By this he means young firms, most of which are small, have a greater rate of exit (death), and appear to maximize escaping death by jobs growth which propels them out of small size classification (p. 24ff). [See also, Ron Jarmin “Longitudinal Data for Entrepreneurship Research from the U.S. Census Bureau”, U.S. Census Bureau, August 2010)]. This phenomena accounts for the attractiveness of a small business strategy which centers around start ups. The casualty rate is high, but the firms that do escape death grow significantly and are serious job creators. In essence, this is the traditional strategy followed by venture capital firms which count on the success of a very few winners to vastly overcome the losses generated by the numerous firms that die.

The attractiveness of a small business strategy is that it centers around start ups. The casualty rate is high, but the firms that do escape death grow significantly and are serious job creators.

The start up “in and out pattern” sets a stage on which other researchers can explore what differentiates those firms which can grow and create jobs and which die. Jarmin emphasizes what he calls “idiosyncratic factors” such as differential ability of the firm, its entrepreneur to learn, to access capital, and increase productivity (especially critical). In addition, Haltiwanger finds that industry sector accounts for differential rates of successful in and out start ups, as well as the differential rates of new firm formation (firm entry rates). Not all sectors are equally successful. Firm entry rates are low in manufacturing and highest in services, wholesale and retail [this is no shocker to anyone who has financed a restaurant].

Spencer Tracy, Zoltan J. Acs and William Parsons, Corporate Research Board, LLC, Wash DC for the SBA Office of Advocacy, June, 2008.

Tracy et al really begin their story with the 1994-1995 David Birch. Birch’s gazelle-concept. “One conclusion [of 1994 Birch] was that the distinction between small and large firms as job creators is of less importance–most jobs are created by gazelles, which are firms that are neither large nor small…. to classify them [gazelles] by their size is to miss their unique characteristics: great innovation and rapid job growth” (p.5) Birch classified firms into three categories: our infamous, fast-growing gazelles, mice which are small, largely stagnant-job wise firms, and elephants or large firms that lose jobs.

Tracy et al focus on the gazelles which they relabel, mercifully, as “high-impact” firms. High impact firms, Tracy alleges have a “disproportionately large impact on employment growth, revenue growth, and … productivity”

A subsequent literature followed the Phase II Birch approach, a literature, summarized by Magnus Henrekson and Dan Johansson (“Gazelles as Job Creators”, Small Business Economics, Springer, Vol 34, No 2, p.227-244) which concluded that ‘net employment growth rather is generated by a few rapidly growing firms-so-called gazelles- that are not necessarily small and young….On average gazelles are younger and smaller than other firms, but it is young age more than small size that is associated with rapid growth. Tracy et al focus on the gazelles which they relabel, mercifully, as “high-impact” firms.

High impact firms, Tracy alleges have a “disproportionately large impact on employment growth, revenue growth, and … productivity” (p. 6). These “high-impact firms play an especially important role in the process of job creation over time compared with either the plants of large existing firms or very small start ups that tend not to grow [mice].

Tracy et al focus on the gazelles which they relabel, mercifully, as “high-impact” firms. High impact firms, Tracy alleges have a “disproportionately large impact on employment growth, revenue growth, and … productivity”

Tracy et al’s study hopes their research will better clarify the role of start ups by better understanding “if” and “how long” it takes for a start up to become a high-impact firm. They also observe that much economic development effort is placed on attraction of new plants and offices and that typical economic development small business programs are focused on new firm start ups or helping disadvantaged firms. All this almost paradigmatic economic development effort may be misdirected depending upon what we can learn about high-impact firms.

Instead, Tracy et al hint that a better knowledge of who, why and how high-impact firms evolve may favor economic development strategies such as business retention and economic gardening. The secondary role these strategies play, Tracy et al further allege, is that “very little is known about second-stage companies (as the Edward Lowe Foundation calls them [and we will study in the third article of our small business trilogy] or companies on their way to rapid growth (p. 7). So Tracy et al want to know more about these former gazelles, now high-impact firms.

The first question Tracy et al pose is “how do high-impact firms interact with the [ macro-economic] economy”? High impact firms can create jobs through (1) innovation, either create it or use somebody’s else’s innovation, (2) productivity enhancements (difficult to measure at firm level), and (3) net positive employment creation which is what is usually measured (p.Tracy, p.8). They allege these characteristics or firm dynamics associated with high-impact firms “implies these firms are involved in activities that have a ‘material’ impact on the economy. [The Curmudgeon must comment that the linkage of high-impact firms to these three firm dynamics is more asserted than demonstrated in the article and whether or not, logically or not, that innovation and productivity in particular are attributes associated with these high-impact firms is more a matter of belief or an extension of logic, than a proven fact].

In any case, Tracy et al believe there is a sketchy consensus in the literature on sector-industry, size distribution and job creation and it suggests that “passive learning” versus active learning (r&d, applied research) is more important than existing capital investment or sunk capital. Instead firm growth is more dependent on the efficient utilization of assets not their size or their access to capital. Who cares, the reader screams?

Tracy et al are trying [we think rather desperately] to suggest that individual sector differences, say between manufacturing and the service sectors, are overridden by the need by all sectors and industries to efficiently employ the assets and resources they possess. In essence, these authors are trying to deal with a database that includes all industries and sectors and trying to develop a “theory” as to why they can explain why high-impact firms of all sectors can share a common set of drivers which account for the success of high-impact firms as a category of firms (pp. 8-12).

High-impacts firms DO exist–at least in hindsight. But it is not at all clear theoretically as to what distinguishes between a high-impact firm and a low-impact firm.

[We include this effort by Tracy et al in our review because we do not think this particular argument was well presented and, we feel, it’s weakness is a material to their argument and findings. They, in fairness, do also allow for other “theories” such as “noisy selection and entry”, “idiosyncratic cost disturbances,” and “active and passive learning by the firm and its leadership”, the first being more sector-sensitive and does include access to capital and physical assets, but, the takeaway in the Curmudgeon’s estimate is that Tracy et al, and the general literature, have some difficulty in explaining WHY high-impact firms exist. The database indicates high-impacts firms DO exist–at least in hindsight. But it is not at all clear theoretically as to what distinguishes between a high-impact firm and a low-impact firm.

This is a shaky foundation for the subsequent articles in the third review and for the high-impact concept itself. If the Curmudgeon’s concern is warranted, economic developers will be hard-pressed to step in and definitively understand how to help the firms identified as high-impact. This ambiguity will be worsened by the tendency in the literature/profession to assert and assume reasons, theories, and models as to why these high-impact firms are high-impact. But, we repeat, at this time, the why of high-impact firms existence (and decline) is unclear and an economic developer who blithely assumes they instinctively and definitively know the answer to these concerns is skating on very thin ice]

Back to more solid ground. Tracy (p12) finds that a 2008 SBA study supported the finding that new business formation [i.e. start ups] does lead to gross or “total U.S. employment growth in the year the formations [birth] occur”. Although the effect decreases in the years after the businesses are formed, the effect does not become negative (p12). Subsequent growth in the fourth and fifth years of existence does occur overall and for the five year period following a start up’s birth is positive. Over their first five year period of life, start ups on the whole do create jobs.

Market entry of small new establishments [fewer than 20 employees], almost exclusively single unit establishments (not branch establishments) results in a strong positive initial effect that decreases over time and is negligible after six years. … New establishments of firms with 20-499 employees [exhibit] positive effects [in employment] after one year and reaches a maximum after five years before it decreases again. These so-called gazelles are able to increase their level of productivity sooner after entry due to their size and preconditions.

Furthermore, they challenge existing firms and increase the competitiveness of surviving existing firms. … The entry of firms or new establishments with at least 500 employees leads to a strong negative employment effect [in other existing firms in the industry, hence] the long-term employment effect [industry-wide, but not for the community with the new business formation] may be negative, but it probably takes more than six years to become visible (p.13-14)

New business formations come in all sizes and that very small firms do have net positive employment growth, but it is not substantial, i.e. small business is not necessarily primary in net job growth for the economy or your community

[this big silent,time-lagged killer–“creative destruction” at its most classic– removes inefficient firms/establishments from the markets and strengthen those that can adapt, but economic developers are going to have a tough time trying to figure out who in their community would be affected by a new firm creation in another community, probably out of eyesight. This is the so-called “elephant effect which may have been captured by Birch in 1994-95]

The above indented paragraph demonstrates that new business formations come in all sizes and that very small firms do have net positive employment growth, but it is not substantial, i.e. small business is not necessarily primary in net job growth for the economy or your community. This does correspond with Neumark’s finding discussed in our previous review “Ghost of Christmas Past”. Tracy et al also suggest that firms 20-499 can foster positive effects on the community of a more substantial nature, however. Tracy suggests that large new business formations (>500) can help the community in which they locate, but unleash a silent, possibly invisible creative destruction against existing firms in other communities. [And one wonders why economic developers are so paranoid?}

Is size really important viewed from this perspective? No! New business formation (age/young/older), is the critical variable.

Tracy et al: Methodology and Definitions

At this point (p. 16) Tracy explains his data set the ACSL (you don’t want to know how he compiles this data-it includes D&B DUNS Market Identifier file, BLS Industry Occupation Mix, and Census Bureau Public Use Micro data Sample file) and methodology. Tracy redefines Birch’s gazelles. In 1994 Birch had defined solely in terms of substantial REVENUE growth (sales doubled every four years), BUT DID NOT INCLUDE EMPLOYMENT GROWTH. Tracy further notes that Birch’s gazelles, based on revenue only, included a large number of firms WHICH DID NOT CREATE ANY JOBS at all and even lost jobs (p.17). In so doing Tracy relabels his transformed gazelles: THE HIGH IMPACT FIRM.

[The Curmudgeon capitalizes because he is talking louder and wants the reader to hear him more clearly. If he underlines and capitalizes, he is screaming. If he emboldens the material, head for the hills]

For Tracy the High-Impact firm has both substantial revenue and employment growth (he develops an indicator, the employment growth quantifier, to measure employment growth). He applies all this to the 1998-2002 period as his base period [which if you remember was the recession time which the high tech bubble burst] but to assess before and after effects the total period under observation was 1994-2006.

The original research of Birch and those who critiqued Birch did not enjoy the luxury of watching the same firm over an extended before and after period. The expanded time period exposed what probably was always the critical variable, age.

[Here we clearly see the impact of better databases. Tracy et al is in the position of doing a “before and after” analysis of both high and low impact firms. We are now in a far better position to identify “age” as a critical variable and assess how the individual firm by size classification and sector can evolve over time. Frankly, this is a major reason why “smallness-size” depreciates in value as an independent variable. The original research of Birch and those who critiqued Birch did not enjoy the luxury of watching the same firm over an extended before and after period. The expanded time period exposed what probably was always the critical variable, age. This is another support for our position that database and methodologies are central to a proper understanding of the role and power of “small business” and job creation]

Tracy et al organize their findings to answer twelve questions (p. 19), but we shall pick and choose those findings which in the Curmudgeon’s judgment best fit the themes we have developed in this review. Obviously, the reader is free to check out the total article and cross check or complete your assessment. A final point which will become more relevant as we proceed into our third review, Ghost of Christmas Future, is that Tracy et al distinguish in their findings between gazelles and high-impact firms. Gazelles use Birch’s revenue only definition and high-impact firms use revenue and employment growth. Our focus is more on high-impact.

High impact firms (299,973 firms or 5.2% of all firms) created 11.7 mm jobs in 1998-2002 period. “While firms in the 1-19 employee firm size were most numerous, most of the jobs created were created by the 500-plus firm-size. In fact, the 500-plus firm-size class created almost as many jobs as both of the smaller firm-size classes combined …”

His findings included:

1. High impact firms (299,973 firms or 5.2% of all firms) created 11.7 mm jobs in 1998-2002 period. “While firms in the 1-19 employee firm size were most numerous, most of the jobs created were created by the 500-plus firm-size. In fact, the 500-plus firm-size class created almost as many jobs as both of the smaller firm-size classes combined …”[reader must remember that “low impact firms are not counted in this finding. If they were included, the jobs lost by low impact 500-plus firms would offset the positive job creation of the high impact 500-plus firms. This negative offset from low impact 500+ firms means that UNDER 500-plus employee firms exhibited NET job growth and 500-plus firms as a whole (both low and high impact) exhibited NET job loss.] (p. 20).

2. Tracy also found that these high impact firms were older when compared to the low impact firms. “For the 1-19 firm-size class the average age is about 17 years. This increases to about 25 years for the 20-499 size class and to 34 years for the 500-plus class. (P.22)

3. WHAT ABOUT START UPS? Having previously spent a considerable time developing a case for the importance of start ups and job creation, his findings were that 0-4 YEAR OLD FIRMS ACCOUNTED FOR ONLY 2.8% OF HIGH IMPACT FIRMS (LESS THAN HALF THE RATE FOR ALL SIZE FIRMS). IN FACT ALMOST 95% OF HIGH IMPACT FIRMS ARE OVER FIVE YEARS OLD (p. 22) and certainly not start ups. Age is still important to net new job creation, but notice, older, not the very young firms are core component of high-impact firms (pp. 22-28).

0 – 4 YEAR OLD FIRMS ACCOUNTED FOR ONLY 2.8% OF HIGH IMPACT FIRMS (LESS THAN HALF THE RATE FOR ALL SIZE FIRMS). IN FACT ALMOST 95% OF HIGH IMPACT FIRMS ARE OVER FIVE YEARS OLD (p. 22) and certainly not start ups.

4. To be sure, Tracy admits that the low impact firms in each category are also older than the high impact of each size classification. Still,high-impact firms are not likely to be youngest firms (including start ups). Indeed, just the opposite. High-imact firms are much more likely to be older firms in your community (p.24).

5. Also, when Tracy et al studied other time periods, they observed that “Most, if not all, of the growth in employment comes from the 300,000 high impact firms in the economy over any four year period. Depending on the time period studied, this is about evenly split between firms with fewer than 500 employees and firms with more than 500 employees. Therefore, it would appear that both small and large firms contribute about equally to employment growth. (P.28)” Yet, …

6. … while the low-impact firms in the 0-19 and the 20-499 firm-size class exhibit either no change or a slight increase in average employment size, the 500-plus firm-size exhibits a persistent and consistent decrease in average firm size. Low impact large firms decline the most and at a greater rate. This offsets the growth rates of the high impact 500-plus firms (p.28) [Perhaps, one can suggest that the impacts of firm destruction (death and dying) is a characteristic of large firms which tend to be older firms]

Tracy et al believe a diversified economy versus a specialized one does better given that high impact firms cut across all sectors and are so volatile (p.30-32) [how this fits into the cluster approach with targeted gazelle-like industries is certainly a relevant question?

7. In any case in what industries are the high impact firms found? The high impact firms for the 1998-2006 period “exist in virtually all of the 2-digit SIC codes”. Perhaps, equally important is that the “percent of high impact firms [for each SIC code] varies significantly over time [which to the Curmudgeon suggests that the business cycle is playing a role in the performance of these high-impact firms–this is a not unreasonable assumption]. Tracy et al believe a diversified economy versus a specialized one does better given that high impact firms cut across all sectors and are so volatile (p.30-32) [how this fits into the cluster approach with targeted gazelle-like industries is certainly a relevant question for which the Curmudgeon has no answer].

8. As to geography Tracy singles out the approaches suggested by Jane Jacobs, Michael Porter and Richard Florida who, Tracy says, “argued that these firms [which the three authors believe constitute the best candidates for economic growth] are located in high tech regions and that most of them are high-tech firms by nature”. Tracy’s findings suggest each of the nine census divisions score about the same with very little variation, but the states with the highest ratios [such as Alaska, Arizona, Wyoming, South Carolina, North Dakota and Virginia] are not especially known as high-tech geographies. (p. 33-35). Tracy et al are not very supportive in regards to geographic bias in the location of high-impact firms. To assess geography we would need to look at Porter, Florida and Moretti and determine how age and size of firms entered into their calculations and definitions.

9. More interesting was his direct challenge to advocates of density as stimulus for innovation and knowledge-based agglomeration (Porter certainly, and Edward Glaser). Tracy finds that one-fourth of high impact firms are located in rural areas; almost another 25% are NOT located in metropolitan areas. The percentage of high impact firms in central city business districts ranges from 10.5% – 8.8%. The highest percentage (33%) of high impact firms are located between 6 and 15 miles of the CBD (i.e. the mediocre suburbs) (p 36-37).

10. Tracy wraps up his analysis by asking what “firms were before they became high-impact firms”. To answer the question he creates six post-takeoff high-impact firm patterns. The categories. based on the rate and consistency of revenue and employment growth previous/following take-off (p. 38). Only 9% of the high impact firms were born in the previous period (these would be “young” firms). Less than 2% of the high impact firms were high-impact in the previous period as well. Fifty-two percent of high impact firms exhibited “no change in employment or revenue in the prior period. “IN SHORT, HIGH IMPACT FIRMS SHOWED NO SIGNAL OR MIXED SIGNALS AS TO THEIR SUBSEQUENT POTENTIAL IN THE YEARS PRECEEDING THEIR GROWTH PERIOD” (p. 40) [Good luck finding these guys, fellow economic developers]

“IN SHORT, HIGH IMPACT FIRMS SHOWED NO SIGNAL OR MIXED SIGNALS AS TO THEIR SUBSEQUENT POTENTIAL IN THE YEARS PRECEEDING THEIR GROWTH PERIOD”

11. The post-takeoff patterns showed that overall 31% were mixed decliners (declined at least two years and over four years revenue and employment decreased–[you know, the gazelles in your community with three broken legs and hemorrhoids]. “In fact, with the exception of a small number of (1-19 employee firms) that stay high-impact or show mixed growth, most of the smallest firms exhibit some sort of decline (p. 41).

The results for the 20-449 classification are somewhat better, and 30% of these high-impact firms subsequently exhibit “constant or mixed growth” (p. 41). However, the 500+ employee firm does even better. Eight per cent, double the rate of smallest firms, STAY IN HIGH-IMPACT growth in the subsequent years. Fifty per cent of the large firms exhibit “constant or mixed growth” and 75% per cent of surviving large firms DO NOT DECLINE (p. 41).

“Clearly being a high-impact firm in the previous four years has a significant impact on firm performance in the subsequent four years, and the effect is more evident as firm-size increases p. 41).

Concluding Observations Regarding Tracy et al

The identification of a high impact firm, like a cluster, is an abstraction to those of us in the field. On faith, we assume it exists, but how to actually see, touch, visit and assist

that high impact firm is not evident.

[It would appear that using his database Tracy has in hindsight culled out the top employment/revenue creating firms, intellectually relabeled them as high impact, and reported ex post facto that they created 11.7mm GROSS jobs. The other 95% of firms, however, in each size classification need to be joined with the high impact firms in order to judge if the size classification as a whole is a NET job creator and at what rate it creates net jobs.

An economic developer gazing into his community, however, does not have the means to ascertain and identify these high-impact firms which may or may not exist. No doubt he or she could send out a memo to the firms, but a business retention job survey could instead be tweaked.

The issue of whether the economic development official can assume that the characteristics of the 1998-2002 period have continued to the present might mean assuming that the macro-economy and changes in that economy have little or no effect (i.e. the 2007-2009 Great Recession has not changed the industry landscape). This is a quite a leap for anyone to make, given that we poorly understand what really differentiates a high impact from a low impact firm. Also, our last article in the current issue, from the Kauffman Foundation, will observe, and be concerned, that the Great Recession has affected the structure of our traditional job creating pattern.

The identification of a high impact firm, like a cluster, is an abstraction to those of us in the field. On faith, we assume it exists, but how to actually see, touch, visit and assist that high impact firm is not evident. The other issue is that even if one could identify and assist high impact firms, wouldn’t an economic developer also need to assist the low impact firm, the elephant, or at least its workers, as it hemorrhages jobs. Helping the strong get stronger may appeal to the academic, but it is not likely to appeal to the unemployed, their families, the newspaper, the unions, and the politicians who sign your paycheck.]

[Spencer Tracy’s argues that high impact firms, not small business per se, creates the most jobs overall for the American economy. He argues that small firms and large firms can be high impact and that most of the smallest firms are not gazelle like. Small does not equal gazelle in the sense that most economic developers use the term. In the spirit of Hollywood typecasting an older man with a younger woman, Tracy argues that older firms (not the oldest firms but “older, mature” firms) are much more likely to be a high impact firm.

Tracy explicitly questions the perspectives of Jacobs, Porter, Florida and their sense of the dynamics of small job creation. Moreover, he, implicitly, challenges the fundamental dynamics, character, and geographic location of what we understand to be innovation and knowledge-based economics. Then to add insult to injury, Tracy concludes that high impact firms are not only older, but have been laying around the landscape, growing in a rather undistinguished rate for a number of years previous to their “take-off” as a high impact firm.

To make matters doubly worse, these hot, sexy high-impact firms after their take off burst (five years or so), usually slow down, light up a cigarette and, for the most part, cease to be high-impact firms. The smallest firms stop growing the most and the largest hold onto growth at four times the rate of the smallest–so pay attention to the large firms in your community. Startups are not usually associated with these high-impact firms]

Enter the Kaufman Foundation

Dane Stangler and Paul Kedrosky, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, “Neutralism and Entrepreneurship: The Structural Dynamics of Startups, Young Firms, and Job Creation”, Kauffman Foundation Research Series: Firm Formation and Economic Growth, September, 2010

Tracy did his thing just as the we entered the New Normal (2008). That is to say everything went to heck in a hand basket and we haven’t really recovered since [for a more sophisticated assessment of the New Normal please check out our New Normal theme].

As soon as the economy came up for air around 2009-2010, the Kaufman Foundation picked up the small business torch and published a series of articles on Firm Formation and Economic Growth. This series of articles is based on a custom data set, a special tabulation conducted by the Census Bureau (its Business Dynamics Statistics database) at Kaufman Foundation’s request. We will review several of these articles and reports in both Ghosts of Christmas Present and Future (and endlessly blather about their findings).

[One more thing, the spell-check facility associated with this just wonderful HTML application, call it Herkimer, cheerfully corrects as a mistake the word “startup”. It suggests the word “start up”. So the Curmudgeon dutifully changes to start up. Herkimer then, equally cheerfully, suggests I recorrect the word “start up” to “startup”. The Curmudgeon went into this endless loop for several days at the end of which he, equally cheerfully, screwed himself into an empty light sockett (or is it socket?) on his Christmas tree. He compromised in this review, and inconsistently mixed the spellings, fully confident both were wrong. The reader is advised]

If you didn’t pick it up by now, too much Christmas cheer, no doubt. Nobody is talking about small business anymore–instead the focus has warped to high-impact firms, gazelles, startups and age as opposed to size of firms. Now we enter the “structure of firm distribution”galazy. We, like James T Kirk, Spock and the Star Ship Enterprise, have entered into a galaxy where no man has gone before.

[If you didn’t pick it up by now, too much Christmas cheer, no doubt, nobody is talking about small business anymore–instead the focus has warped to high-impact firms, gazelles, startups and age as opposed to size of firms. We, like James T Kirk, Spock and the Star Ship Enterprise, have entered into a galaxy where no man has gone before–certainly not the 1987 Dr. David Birch. Upon reaching this galaxy, we really need to put this all in some sort of context. Stangler and Kedrosky’s article give us a bit of a map to this new-found galaxy, a sort of lay of the land based on understanding better the age (and size) distribution of firms in the American economy. We warn the reader, the Kauffman Foundation will develop a way of thinking about all this, based on this distribution of firms, but we will develop that more in Ghosts of Christmas Future.

[Before we get started, we need to shift the reader from previous articles which focused on the RATES of net new job creation by categories (size or age) or characteristics (gazelle, high impact). The search thus far has been to discover those industry segments or characteristics which disproportionately create more jobs than other segments, categories or characteristics. The Kauffman Foundation, however, is more concerned explaining with improving our understanding of OVERALL job creation or who creates the most new jobs in the American economy. They are especially concerned as to “who” creates these big numbers of new net jobs and “how” they do it. They will reach an answer which will provide context for better understanding the previous articles.

The Kauffman Foundation folk come to the conclusion that startups and young firms (less than five years old) account FOR NEARLY ALL THE NET job creation in the United States in any given year.

[In previous articles in this series, Kauffman Foundation folk come to the conclusion that startups and young firms (less than five years old) account FOR NEARLY ALL THE NET job creation in the United States in any given year (we will explain this in Ghost of Christmas Future). [Is this in contradiction to Tracy and Haltiwanger??? Not really, Kauffman is talking about the absolute number of net jobs, not the highest rates of net new job creation. To repeat ad nausuum, the reader has to be sensitive to the methodology, indicators and databases and the Kauffman folk are using a different methodology ((to be explained), a different database, and they are concerned with the absolute, not relative (rate), number of jobs created by the entire American economy in a certain period of time. If one looks at the sheer, absolute number of net new jobs created each year, Kauffman is correct in asserting that startups and less than five year old firms create an absolute majority of net new jobs each year. The engine of our economic growth is startup and young firms. BUT … that does not invalidate the previous reseach. The Kauffman perspective supplements the previous research and places it in a larger context]

Won’t many of the jobs created by startups and young firms disappear over time and do these new and young firms result in job destruction in existing and older firms as well? YES, absolutely!

Job destruction in young firms, and with other existing firms as well, will occur in a really huge way over several years. Stangler & Kedrosky assert that this subsequent job destruction will not be sufficient to eliminate all the net new jobs created by startups and young firms each year. Startup and young firms together create so many net new jobs each year that they overcome whatever all the other categories of firms produce and destroy each year. Why is it that these startup and young firms can be so powerful and create absolutely so many new net jobs, and yet be very volatile over the next few years? Why are startup and young firms more impactful than all the remainder of the firms, including firms the likes of Wal-Mart, Citicorp, Wells Fargo, Exxon, etc. Are these start up firms “magical”? Are they the perfect expression of creativity and innovation? Are their entrepreneurs the spark of both? Those are questions the Kauffman folk are trying to explain in this article and in others that follow.

Startup and young firms together create so many net new jobs each year that they overcome whatever all the other categories of firms produce and destroy.It is the VOLUME of jobs created by the startup and the young firms that overcome whatever else is occurring in the rest of the firms in the American economy.

The answer is actually very simple. Over the last thirty years or so, the American economy has followed the same basic pattern of job creation (and destruction). The American way of creating new jobs is remarkably stable (at least until 2008) and that pattern of who and how jobs are created rests upon an incredibly huge number of brand new, startup firms being created each and every year. From zero these new firms create, by definition, completely brand new jobs which in absolute number simply crush the combined output of all other existing firms in the economy.

The obvious problem is that most of these jobs created in their first year of operation will be lost/destroyed by the fifth year, and most much earlier than that. The jobs that are lost in the following years are more than made up for by the huge number of new, first year startup jobs that occur in Year 2 and each year that follows. Startup jobs are not stable or long-lasting, there are just a lot of them. It is the VOLUME of jobs created by the startup and the young firms that overcome whatever else is occurring in the rest of the firms in the American economy. There is no “magical” quality to startups.

New and young firms account for between 30 and 40 percent of all firms in the economy at any given year (p. 12). Stangler & Kedrosky, however, are quick to observe that these startups and young firms are not magical in any sense except their volume. We are professionally accustomed to hear boundless platitudes heaped upon certain types of firms, such as innovative, knowledge-based gazelles and creative classes that possess no weakness and are the driver of perpetual economic growth to the clouds forevermore. Wouldn’t it be reasonable to expect that the Kauffman Foundation, proponents of startup and young firms as the central job creators of the American economy, would glorify startups and attribute to them all wonders of goodness, creativity, innovation and productivity?

Well, they don’t! In the Kauffman galaxy, most start ups lose jobs from the day they were created and they are not necessarily fonts of innovation or creativity. Most struggle and fail just as Tracy suggested earlier. These startups as a whole are far from being high-impact firms. But, it must be admitted, most are small (53% are less than fifty employees, p. 13) and new means they are young. Haltiwanger is not wrong. Small firms produce in excess of 60% of all new net jobs in any given year. But again in the Kauffman galaxy, youth is nothing special except there are hordes of youth [whippersnappers] and dwindling numbers of the mature firms.

[ok, let’s regroup! Tracy demonstrated to us that a few high-impact firms create more net new jobs than any other segment of firms operating in the economy. What’s more, these high impact firms are older than five years and therefore do not fit into what the Kauffman folk are saying. How can, even given different methodologies and databases, both be true. Here’s how. Essentially most jobs created in a startup’s first year of operation are destroyed by their fifth year, and only a scarce few of these youngest firms become high-impact firms in the second five year period (remember Tracy works within three five year periods).

Tracy’s high-impact firms then create all these great net, new jobs in their second or third, or fouth five year period, but these new jobs are essentially wiped out by the losses incurred by the low-impact firms during the same five years. In every single year in each of Tracy’s three five year periods, however, there is a brand new crop of startups which is so huge so to dwarf whatever the high-impact and low-impact firms are doing. Make sense? They both can be true as well as Haltiwanger]

[Obviously the overall economy will be negatively impacted, probably significantly, if the high-impact firms did not do “their thing” (i.e. create lots of new net jobs more than anyone else). But the real driver of any single year’s total net new job creation will still remain the huge volume of brand new startups and the residue of jobs remaining from the survivors of last year’s crop of startups, combined with what remains of the crop of startups from three years ago, etc.

It is also interesting that according to Kauffman Figures 8 & 9 (p.13) that the second most productive job creating grouping of firms is those firms with more than 10,000 employees and older than twenty-nine years (about 11% of job creation). Tracy wasn’t completely crazy–and either was Haltiwanger. Again, everybody was right–in their own way]. The Kauffman Foundation authors have read and understand Tracy and his high-impact firms and they wonder in this article how these high-impact firms relate to this overall pattern. [To the Curmudgeon, it seems they wonder if these high-impact firms are simply the tip of a continuing firm iceberg, a more or less natural aspect of any economy (p. 17) or is there something else going on in these high-impact firms. Some firms will do very well at a point in time, others, probably most, will not]

[Don’t worry, no one, including Kauffman is saying these net new jobs created by startups are magic jobs, superior jobs, or stable jobs–in fact they are most likely the opposite. Rather Kauffman is saying, for better or worse, the way our American economy has operated over the last thirty years has been to live off this annual tsunami of startup jobs (sort of like the annual flooding of the Nile). Without the flood of new startup jobs each year, there would be virtually no net job creation by the entire American economy]

So what happens if the flood of new startup firms doesn’t happen? We are up the creek without a paddle (sorry, this Nile metaphor is getting old fast). That is what has happened in the post-2008 New Normal period. We shall deal with that topic in our last article, the Ghost of Christmas Future.

Stangler & Kedrosky do open up some interesting issues. One is the issue of firm death; only the tinest fraction of companies appears to survive for longer than forty years. When we combine this with the sheer volume of low-impact firms which Tracy uncovers, we wonder if healthy, growing firms are the exception, not the rule. What implications might that have for our sub-state economic developers?

Secondly, and perhaps more important, is that job creation in our economy rests on what Stangler & Kedrosky call “CHURN”, the annual flood of startups and their steady hemorrhaging of jobs through year five. Churn is the real life reality of job destruction and firm death that occurs daily; yet another manifestation of creative destruction at work. And while we might be inclined to find ways to increase firm survival, the Kauffman folk rightly observe that age and creativity are not necessarily linked. Old firms can become creative and innovative. But to the extent that increasing firm age could be associated with inhibiting innovation and instead create a degree of stagnancy in the economy, we had better be careful at implementing strategies that artificially prolong firm life. Perhaps a glimpse of the Japanese post-1990 economy might be worthwhile as a counter check.

In any case if we want job creation in our community we had better pay attention to startups and young firms. We must, however, keep in mind that these new born and youngsters are vital not because they are inherently superior or better than, say older or larger firms, but because of the structure of American job creation requires large numbers of these start up lemmings. Our economy is based on, revolves around, a flood of new startups each year; most of which are destined to quickly disintegrate.

But Stangler & Kedrosky leave us as economic developers with a clear imperative. If we want job creation in our community we had better pay attention to startups and young firms. We must, however, keep in mind that these new born and youngsters are vital not because they are inherently superior or better than, say older or larger firms, but because the nature of the American (and other developed nations appear to be similar in their job creation structure) structure of job creation. Our economy is based on, revolves around, a flood of new startups each year. This, almost skeptical perspective, is labeled “a neutralist view”.

While not etched in stone, our pattern has lasted at least since 1977 and has been characterized by “a more of less steady inflow of startups; more or less consistent survival rates from year to year; and roughly equal levels of gross job creation and destruction in older companies that tend to cancel each other out on a net basis” p. 16).[ Can we change this pattern? Should we want to change this pattern?]

Neutralists see our present pattern of firm size and age distribution as a normal and natural outcome of the aggregation of births and then eventual death of firms in the overall economy. Over time this annual dynamic hardens to become a long-term pattern, a “structure” of firm distribution and dynamics unto itself. It is neither good nor bad; it just is! In this neutralist view the structure and dynamics of the pattern of firm birth and death determine the extent of the economy’s ability to create new net jobs.

The durability of the old and long-standing pre-2008 pattern based on new start ups, however, may be not only challenged, but dying. Like Scrooge who fears the grave he sees is his own. In horror, he wonders if he can redeem himself through good actions and a warm and loving heart. Or has the page turned forever?

But Stangler & Kedrosky appear to be a bit uneasy with the mechanical and structural pattern of job creation which they have discovered. They end this article, and they will write several more, on ideas on how we can at least tweak this pattern of job creation. But as Scrooge sees the Ghost of Christmas Present depart, his fear increases rather dramatically. What will the Ghost of Christmas Future say to him?

With the threat of the New Normal very much in evidence, with Ben Bernanke acknowledging unemployment exceeding 6.5% for several more years, with Carmen and Rogoff suggesting finance crises persist for decades, and with increasing concerns about the adverse effects of innovation and productivity (i.e.e creative death) on structural unemployment, the durability of the old pre-2008 pattern may be not only challenged, but dying.

Like Scrooge who fears the grave he sees is his own. In horror, he wonders if he can redeem himself through good actions and a warm and loving heart. For the answer to these hopes and fears, we await the spectre of the what will be. the Ghost of Christmas Future.

For the answer to these hopes and fears, we await the spectre of the what will be. the Ghost of Christmas Future. He will arrive about a week after the Three Wise Men and the Epiphany. (That’s around January 15th)

Comments

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.