Detroit: Why Bankruptcy? Why Bankruptcy Now?

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

City of Detroit

Like it or not, the Detroit bankruptcy filing is a page turner. What insights and lessons might an economic developer glean from it? That is our task in this issue. Since July 18th when the City of Detroit filed for the nation’s largest ever (in terms of debt) municipal bankruptcy, the Curmudgeon has been buried under an avalanche of different ideas explaining how Detroit got into this revolting situation. There have also been a pile of development-revitalization suggestions, as well as blame-placing. Blame there is–not surprisingly, blame aplenty.

The ever-reticent Krugman, for example, blames job sprawl and suburbs, and a ton of media folk blame the decline on the auto industry or they resuscitate age-old deindustrialization woes. Others blame unions, still others wonder about the role of race, state government, the city’s past political leadership–and a bunch of extraordinarily brilliant commentators cite the obvious–that almost everybody left town. What could the Curmudgeon possibly add to this cacophony?

What the Curmudgeon proposes is simply to step back a bit and subject some of these “causes of bankruptcy” to a review. Do some of these alleged “causes” of bankruptcy have merit–is there someone-thing more than any other more responsible for the bankruptcy filing?

Right off the reader might appreciate the Curmudgeon “take” on the bankruptcy filing. Detroit may, or may not, be an extreme case of municipal decline–but not all legacy, or chronically declining cities are on the threshold of bankruptcy. Bankruptcy could be looked at as the culmination of urban decline. We prefer to view the bankruptcy as the necessary first step to a future revitalization. The bankruptcy can, arguably should, be used to remove those factors which make future investment in Detroit either unrealistic or a waste of money, time and effort.

Economic and population decline has not been a stranger to Detroit over the last half century. Why does it matter now? Some of the factors cited as causing Detroit’s fiscal collapse have been around for such a long time that, while they may be part of the background, they are not the reason for the bankruptcy. Nor are several of the factors frequently cited as causes of the bankruptcy going to be part of the solution. Suburbs are not going away and the auto industry that built Detroit is not likely to return to Detroit any time soon. The national economy is the national economy and it will do whatever it will do.

In our view, the immediate trigger, and prime cause, of the bankruptcy filing is (political agendas aside) unfunded pensions and retiree health care benefits. Until Detroit fixes that problem, it makes little to no sense to pour funds in to revitalize or stabilize the city, its infrastructure and neighborhoods. Bankruptcy is the first step in the rebirth of Detroit–and yes, a lot of people will be hurt by it. It is the way in which the pension–and more importantly, the retiree health care benefits are resolved that offer the most page-turning potential.

The Curmudgeon will be the first to admit that this is a cold-hearted approach to municipal bankruptcy–he really does not want or enjoy seeing the suffering of individuals and families that will result from bankruptcy resolution. Also, he is fearful, that the filing will eventually be resolved in precedential ways which will negatively affect a lot of cities in the future. Detroit’s filing and bankruptcy revolution has the very real potential to be a page-turner in municipal history. Both the human loss and the potential page-turning consequences affect all economic developers for years to come. This is an event worth watching as it unfolds.

In any case, in the sections below, we shall pose several questions, hopefully pertinent to economic developers. First we shall take a gander at some background issues which have been cited as responsible for Detroit’s bankruptcy and secondly we will focus on the bankruptcy filing itself (which means a more fiscal focus on debt–bankruptcy which after all is a process to resolve unsustainable debt obligations).

Did Detroit’s political leadership stand idly by and watch the city decline?

Let’s start with Coleman Young’s election in 1973. Contrary to the image Young seems to enjoy today (as a rabble rouser-populist, divisive black activist, anti suburban–all of which he was), Young’s administrative style was quite Neo-Liberal, i.e. municipal fiscal-budgetary and employee cutbacks, increased taxation, and close working relationships with the private sector.

First things first, however. Off and on throughout his administration Detroit appeared close to default–almost every major city in the Northeast and Midwest was in genuine financial crisis at this time. New York City taken over by Big Mac in 1976 and Cleveland (which defaulted–but did not enter bankruptcy– in December 1979 both narrowly escaped bankruptcy, largely because structural or fiscal alternatives were available to them. During these early years, until 1984, Young reduced debt levels from about $3 billion (2013 dollars) to about $1,5 billion (2013 dollars). In 1975 Young, with the city’s unemployment around 20%, confronted the crisis by laying off one in five city workers. State aid to Detroit doubled and the state effectively took over the City’s Library System. Each year thereafter a sizeable deficit had to be closed–after 1984 often by increased borrowing. By the end of his administration Young’s Detroit non pension debt burden once again exceeded $3 billion (2013 dollars).

It all came to a head in 1981. Triggered by a 1980 court decision which awarded $50 million additional funds to the city’s fire and police, the city spiraled into an $80 million deficit (1980) and a $120 million deficit in 1981. To confront the crisis, Young raised the municipal income tax rate for city residents by 50% and 200% for nonresident commuters. He campaigned successfully and won a referendum vote on the tax increases. Detroit avoided default–and moved on to its “golden years” of the administration of Dennis Archer (1993-2001).

Secondly, the economic development cornerstone strategy throughout his twenty year period in office (1973-1993) was CBD and manufacturing renewal in alliance with corporate movers and shakers. Young was committed to retain a significant General Motors presence in Detroit and mitigate the downsizing of the automotive industry. Probably the best example of Young’s GM commitment is the destruction of the Poletown neighborhood.

As background to Poletown, the late 1970’s-mid-eighties were transformative years for the American auto industry. Honda, the first Japanese automaker to build a US facility (Marysville Ohio), was in process of investing (over the 1980’s) $2 billion in new facilities–in just Ohio. Nissan, Mazda, and Toyota, as well as Mitsubishi and Subaru, followed suit. During the eighties, then, Auto Alley was born. Coleman Young demanded that General Motors aggressively consider the City of Detroit in any expansion. GM, needing to compete with the new technology and innovation introduced by the Japanese (as well as achieve fuel reduction demands to counter the oil crisis and recession), responded by requiring of Detroit no less than one square mile of cleared land, deliverable within eighteen months, on which it would build a modern, competitive facility (a Cadillac plant).

Some argue1 this was a GM bluff, while others2 argue that GM “manipulated the political process to get an ideal site without much cost…”. Whatever–Coleman Young was determined to make such a site available to GM in the allotted time period. Working with the adjoining Polish suburb of Hamtramck, Detroit got state and federal funding in order, condemned 1000 homes (including two Catholic churches (sixteen churches in total), removed about 4200 residents (largely white, Poles), relocated an estimated 600 businesses, and delivered the site on time and under budget to GM.

The facility was constructed and is still in operation with a workforce of about 3000 in 20133.To be sure, one facility does not an auto industry make and the controversy, image and heartbreak associated with Poletown remain with many to this day–indeed, eminent domain as an economic development tool never was quite the same (the Michigan Supreme Court has since reversed its Poletown decision). But it would not be fair to say that in this critical period Coleman Young and Detroit sat idly by and watched the loss of automotive jobs within the city.

The administration of Dennis Archer (1994-2001), while like Young’s was a mixed bag–but on the whole, we sense that Archer was able to keep Detroit’s head above water. Almost all agree that he moderated the tone of politics in the city, and between the city and the suburbs. He continued Young’s focus on working with white business and corporate leaders. $11 billion of projects were built in the course of his administration–that helped stabilize the tax base, unemployment, and population migration. During Archer’s administration crime rates went down and employment levels went up.

Archer poured $100 million into Detroit’s empowerment zone. City employment levels continued their decline, and budget deficits were avoided. Downtown employment, estimated at 421,000 in 1994, was 417,000 in 2000. Detroit City unemployment during the same period dropped from 15.8% to 7.3%. The Renaissance Center, negotiated by Archer opened for business in 2003. Archer built the new Tiger Stadium–a very controversial use of tax dollars and incentives–and rightfully or wrongly, he made a deal with casinos to build three casinos which generated an estimated 8,000 jobs and $150 million in new taxes. The casino taxes substituted and pretty much compensated for declining property and sales taxes. Worth note is that when Archer left office in 2000 overall non-pension related debt was just over $4 billion (2013 dollars)–about the same level as held in 1970 (2013 dollars) . It can be argued that Detroit, as of 2001, had responsibly adjusted to past major population declines and their social consequences.

The administration of Kwame Kilpatrick is another matter. It’s hard not to do a hatchet job on somebody that wound up in jail, along with half his family and most of his “friends” (including the wife of Congressman Conyers who was on the City Council). Detroit’s ex-Treasurer and several pension fund trustees have since been indicted in a pay-to-play scandal. (Last week, on October 11, 2013 he was sentenced to twenty-eight years in jail). During the Kilpatrick years (to be fair he got caught in the beginnings of the Great Recession and General Motors-Chrysler bankruptcies) 25% of Detroit’s population headed for greener pastures elsewhere. Downtown employment plummeted to 270,000 from 417,000. From 2005 onward budget deficits skyrocketed–and by any stretch city finances and pensions were badly mismanaged. The state, controlled by the same political party as Kilpatrick, could not in good conscience wrap their arms around him and stuff his pockets full of more money. A state-led bailout was out of the question. Indeed, Governor Granholm was responsible for “blowing the whistle” on Kilpatrick. Besides, Michigan state government in this period had its own problems, politics and priorities which tended to consume its attention.

Our last thought concerning the Kilpatrick administration’s fiscal heritage was than Detroit’s non pension debt burden in 2001 when Kilpatrick assumed office was a bit above $3 billion (2013 dollars). By 2005, at the end of his first administration and his reelection year, Detroit’s non pension debt burden had increased by 300% to nearly $9 billion (which included nearly $1. 5 billion of mis-labeled pension related debt testifying to the compromised nature of fiscal management during these years).

In the course of all this fun, it might be mentioned that Kilpatrick, in the midst of many of these scandals, was overwhelmingly reelected in 2005. Nobody forced Detroit citizens to vote for Kilpatrick and …well… Enough said. You get what you vote for!

In 2009, the current mayor David Bing took over to finish out Kilpatrick’s remaining term after he headed off to jail. In January, 2011 Michigan’s current Republican governor Snyder assumed office.

Did Suburbanization and the Flight of Whites and Jobs Push Detroit in Bankruptcy?

Our natural inclination is to answer this question would be to sarcastically observe that if this the answer was yes, every Northeastern and Midwestern central city would and should have been in default by 2013. Detroit is in bankruptcy and the other cities ain’t.

Let’s not debate the obvious. Whites did move out of Detroit and left the city to blacks, many of whom were relatively new migrants of the “Great Migration”. In 1940 Detroit was 91% white; by 1980 Detroit was majority black (66%). In 2010, the 1940 percentages were almost turned on their head with whites 11% and blacks 83%. Also, let’s freely acknowledge that the 1967 race riot, one of the nation’s worst, had an undeniable and negative effect on Detroit’s population and job loss through the seventies. City-suburban racial tensions were arguably considerably worse than any other major metropolitan area in the nation.

Clearly, white flight and suburbanization were major factors in explaining central city decay–throughout the entire Northeast, South and Midwest. The fiscal crisis which confronted by Coleman Young as described above was likely the consequence of white (and black middle class) suburban migration. Residential segregation and spatial job mismatch resulted,–in Detroit and most other Northeastern-Midwestern cities.

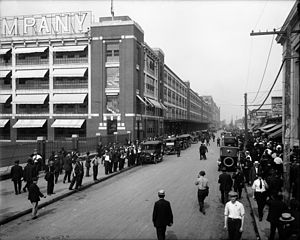

The loss of Detroit’s pre-1980 manufacturing jobs, however, was actually more pronounced than population losses. In 1947, 3272 manufacturing firms resided in the City (overall employment 338,400); by 1972 there were 2,398 manufacturing firms (180,400 employees)–a loss of over 150,000 manufacturing jobs (-47%). Detroit had lost nearly half of its manufacturing employment by 1972. Only a decade later 105,700 manufacturing jobs remained in the city by 1982–a loss of almost seventy percent of Detroit’s 1947 manufacturing employment4 . In 2013 an estimated 23,000 remain.

Still, the central point is that it was the suburbanization of manufacturing, not the collapse of the auto industry that stripped Detroit of its manufacturing heritage. And that was a done deal thirty years ago. The rise of Auto Alley merely removed the lipstick from the corpse of Detroit’s manufacturing employment. (For those desiring a more detailed review of the impact of Auto Alley on Michigan and the Detroit Big Three see Part II at the end of our review article.)

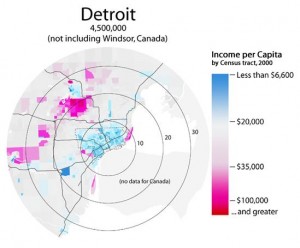

Certainly that gap in does not stop some from arguing that white suburbanization and spatial jobs mismatch are responsible for Detroit’s current fiscal plight. Paul Krugman5, for instance, citing a recent Harvard-Berkeley “Equality of Opportunity” research report, states that “the city may be just too spread out, so that job opportunities are literally out of reach for people stranded in the wrong neighborhoods”. Tell that to Detroit’s Wayne County. Wayne County has essentially lost population since 1960. In the 2000-2009 period alone, Wayne County lost 187,000 jobs and nearly 69,000 manufacturing jobs.

To us sprawl, inequality and job spatial mismatch would have been much more persuasive thirty years ago than it is today. The relevant spatial job mismatch in 2013 is that a Detroit resident had to commute to Kentucky or Indiana, not to Wayne County.

Did Detroit spend itself silly?

Detroit, at the time of its bankruptcy filing had generated a revenue-expenditure imbalance exceeding several hundreds of million dollars annually–and this was projected to grow substantially each following year. Revenues in 2002 were $1.5 (rounded) billion dollars (Detroit’s revenues chiefly originated from an income tax, property tax, excise tax, casino wagering tax, parking and tolls from tunnels and bridges to Canada). In 2011 revenues were about $1.2 billion (about 20% decline). Expenses were $1.4 billion in 2002 and $1.1 billion in 2011–about a 21% decline. Positive general fund end of year balances ceased in 2005, skyrocketed in 2009 and after settling down in 2010, resumed its upward momentum in 2011 6. As a sort of benchmark measure, the Detroit Free Press has reported that revenue in 2009 as about $1.3 billion (2013 dollars)–about the same as Detroit’s revenue in 1952 (2013 dollars). By 1960 revenue hovered around $ 2 bilion (2013 dollars) and stayed a little south of that until 2000. Between 2001 and 2009 revenue declined over 30%. By 2011 revenue had declined to about $1 billion or so. Clearly, the revenue implosion is a post 2000 phenomenon.

As early as 2011 Detroit’s general fund was fiscally imploding and no longer viable without substantial and chronic outside assistance. Why? Was it because Detroit was spending too much and hiring unsupportable numbers of employees?

In 1959 there were 29,004 Detroit municipal employees or 58 employees for each citizen In 1974 (Coleman Young was elected in 1973) there were 27,574 municipal employees7 or about 61 citizens per employee; in 1989 there were 20,036 or about 51 citizens to each municipal employee; in 2002 there were 20,799 employees or 46 citizens per employee. Detroit presently has 11, 645 municipal employees with an average salary of $56,491, about 1 for every 61 residents.

The Washington Examiner using Census Bureau’s 2011 Census of Public Employment compiled a study which demonstrated that at least nineteen major cities in 2013 had per capita city employee ratios far exceeding Detroit’s. San Francisco has 1 to 28 citizen ratio, but Washington D.C. beat it with a 1 to 25. New York has a 1 to 32, Cleveland 1 to 50, Seattle 1 to 56. The same is true in regards to average wage. Oakland’s average wage was $98,705; Los Angeles $93, 517; Seattle $81,488; Sacramento $78,823; Portland $76,186; Jersey City $ 73,220; Newark 71, 267.

Detroit’s 11,645 employees with an average wage of$ 56,491 is not the cause of Detroit’s present bankruptcy filing. A final note on the personnel and wage subject is that over the 2002-2011 period, fire and police employment was reduced by 31% and overall personnel was reduced by 33%. In that police and fire expenditures grew (+22%) in this period, this demonstrates a disconnect between employment levels and expenditures. Pension costs and overtime are the likely chief culprits.

In this context, it is also worth mentioning the $80 million deficit to the general fund caused by the city bus system enterprise agency operations. One might wonder why a separate transportation authority might have plugged a rather large hold in the city’s expenditure deficit.

So, if employee employment levels or wage costs are less the issue–what about a decline in property taxes due to housing abandonment8?

Over the last ten years, Detroit had a peak property taxable value of $10+ billion; in 2011 property assessed value was $9.4 billion–a decline of a mere 7%. Property tax collections, however, had declined to less than an 80% rate. This is probably a combination of socio-economic distress, housing abandonment and bureaucratic inefficiencies. In that property tax revenues were 15% of the general fund, the loss of 20% of property tax projected revenues was certainly a serious hole–and one that would be worse each following year. This loss of property tax revenues, however, in an of itself, was, however, in our opinion, not sufficient to justify a bankruptcy filing in 2013.

The decline of the City’s income tax receipts, almost 30% from 2002 to 2011, also could have caused a more serious deficiency in revenues. The income tax declined in two spurts, 2002-2004 (-13%) and 2008 to 2010 (-21%). Both spurts were directly traceable to serious national recessions than to population exodus and housing abandonment. Moreover, these losses were more than offset by the new found revenues associated with the casino wagering tax which greatly expanded in the post-2005 period.

What was not offset by casino taxes was a post-2002 28% decline in “state shared revenue”. The decline in state funds occurred every year, with one exception, since 2002. The present Republican governor took office in 2011 and the governor throughout the period of post-2000 state revenue decline was Democrat Jennifer Granholm (2003-2011).

In our opinion, the most serious expenditure issue our research uncovered was pension and health care benefit costs which rose from less than 8% of total general fund revenues in 2002 to over 19% of general revenues by 2011 ($195,314,563 in 2002 to $458,479,862 in 2011. By 2011, $.17+ cents of every revenue dollar was needed to pay the annual required contribution to pension and health care benefits (p.10-11). Comparing cities, St. Louis at 8% in 2010, Chicago at 20%, and Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Detroit at 16-17%, indicated these costs are wide-ranging across large cities and that Detroit is at the higher end (p. 11).

The issue of pension costs is further intensified by a 2005, $1.4 billion “certificates of participation” 2025 issuance which increases debt service obligations which are not included in the above figures. Detroit has no fiscal slack and the unabated rise of annual pension and health expenditures since 2002 may arguably be the single most critical factor in the revenue-expenditure general fund imbalance.

To summarize thus far, our initial take is that Detroit has been in serious decline since 1950 and should be at minimum considered as a “legacy city”, a Great Lakes chronically declining central city of the old 1920’s industrial age. At the same time, the picture of Detroit as a hopeless basket case heading for inevitable bankruptcy is very overstated. Detroit kept its head above water until 2000 or so. Clearly, Detroit was hurting and the 1990-2000 decade was for Detroit a more a fragile stabilization than a modest revival which several Northeastern and Midwestern central cities were able to muster. With competent, even if divisive, city government Detroit had more or less weathered a massive social and demographic transformation which had stripped it of most of its manufacturing base. It is possible the heritage of past city-suburban (racial-based) controversy haunted any Detroit’s late twentieth century comeback, and certainly the economic weakness of the state of Michigan as the effects of Auto Alley unfolded hurt also (but affecting more suburban and second-third tier cities, however–but see our Part II if a more detailed assessment is important to you). Post 2000 was another matter.

The City Implodes: Post-2000 Detroit

The triple whammy that hit after 2000 was more than sufficient to render Detroit’s tenuous municipal finance system unsustainable. Detroit no longer had the resiliency to avoid a bankruptcy. After 2010, it was more a question of when.

There is one very awkward and politically incorrect issue which our portrait of Detroit has put aside. From our perspective, Detroit had at some point crossed that not so invisible, but loudly unspoken, line where race had become a critical issue in Detroit’s ability to solve its problems and devise a solution to revitalize. Unlike most Northeast and Midwest central cities, Detroit exhibited a post-1980, relatively robust, black in-migration. By 1980, the Great Migration was pretty much over–not so for Detroit. With more than 4 out of 5 residents black, Detroit was more than a black majority city.

The lack of racial diversity (yes, we are aware that Detroit’s Asian population is growing dramatically) is one thing–but the key element in a revitalization of the city had to include the retention of the black middle class (and working class). But that was not to be after 2000. The post-2000 flight of the black middle and working class was huge. Detroit lost more than a quarter million residents, 25% of its 2000 population, during the last decade. By comparison, Cleveland lost 17% (80,000) and Cincinnati (10%) but Minneapolis-St Paul grew 31%, Columbus Oh 11% and Chicago nearly 7%. Detroit lost the most by far and recorded the highest rate of population loss of major central cities in the Northeast-Midwest. A considerable part of Detroit’s black middle class left the city after 2000.

Brooking Institute demographer William Frey in his analysis of the 2010 census data10 associated “black flight” as a prime factor in Detroit’s population loss (about 41,000 whites left but more than 185,000 blacks). Post 2000 population trend contrasted rather dramatically from the previous decade (1990-2000) when 106,000 whites and about 2,000 blacks left Detroit. Not only was the 2010 decade was the first decade ever that the number of black city residents did not increase, but it was the first decade that blacks left the city in relatively huge numbers. This post-2000 exodus almost inevitably included much of Detroit’s black middle class. The exodus of Detroit’s black middle class was Detroit’s first bankruptcy whammy.

The scandals-mismanagement of the Kwame Kilpatrick administration-family was the second whammy. The Mayor eventually resigned, was convicted of 24 federal crimes including RICO, and went to jail. In 2005 Time Magazine labeled him as one of the nation’s worst mayors, ever. His reelection in 2005 is testimony to a suspicion that effective governance in Detroit would be difficult to sustain in the future. The political reset button had to be pushed.

We won’t belabor the obvious third post-2000 whammy(s): the 20o1-2003 “dot com recession” and the 2008 Great Recession. The weakness and near collapse of the national economy, with all that implies (including two of Detroit’s Big Three Auto firms going into bankruptcy) was, arguably Detroit’s coup de grace.

Suffice it to say, after experiencing these losses, an overall weak national economy (the jobless recovery-remember) and the governmental mismanagement, there was no way Detroit’s precarious fiscal condition could be sustained. Although statisticians and methodologists will someday, no doubt conclusively identify which of these events was the most significant, it matters little to us. One followed the others or overlapped. Any statistical correlations in our opinion are unlikely to shed little real light on the question of which is most important. To argue that any one punch in the gut was the most significant is a bit arrogant, even for the Curmudgeon.

Debt and 2013 Bankruptcy:

At this point we switch our focus to the bankruptcy filing itself. We are not in this review going to comment upon the post-bankruptcy economic development revitalization plan of the City. That would be interesting, we admit, but first things first, let’s get a better handle on the bankruptcy. Detroit’s bankruptcy filing outlined a $18 billion dollar municipal debt structure:

- $2.9 billion (16% total debt obligations) general government operations debt;

- $5.9 billion (33%) Detroit Water and Sewer Department debt;

- $3.5 billion (19%) Unfunded Pension Liability;

- $5.7 billion (32%) Unfunded Retiree Health Care Liability

The usual suspect of municipal fiscal weakness, unsustainable general obligation debt is not Detroit’s chief problem by a long shot. Perhaps, surprisingly, given the media hype, unfunded pension obligations is not the real problem either. The $3.5 billion unfunded pension liability listed in the filing, however, is an especially controversial and, frankly somewhat mysterious number, that seemingly appeared “out of the blue”. This is not to say, Detroit does not have significant pension woes as we shall discover below, but up to the time of bankruptcy filing, unfunded pension liabilities was not thought to be the principal reason for any forthcoming “default”.

Instead, the big ticket items are obviously water and sewer debt and unfunded retiree health care liabilities. Let’s discuss each.

Water and Sewer Debt: Here’s the issue in 2013. The Water and Sewer Department’s portion of the total bankruptcy debt obligations (33%) is the largest single element in the overall municipal debt picture. The City of Detroit’s Water and Sewer Departments pump water and provide waste services for the suburbs. These departments provide infrastructure support for suburban jurisdictions and communities. The latter, however, generate sufficient revenues to, in effect, subsidize city resident rates.

The Water and Sewer Departments11 are classified as “Enterprise Agencies” as are the Airport, Library and Department of Transportation (the municipally owned and operated bus service). Enterprise Agencies are, by definition, meant to be self-supporting. The physical facilities and fixed assets required to provide these services are extensive and especially capital intensive. They break down regularly and are subject to severe quality and environmental regulation and standards. Accordingly, water and sewer debt constitutes the largest segment of the city’s present debt crisis.

In its earlier years city control and administration of water and sewers seemed to work to the City’s advantage. Detroit did not have a debt crisis back then. Its per capita municipal debt burden was among the lowest of the twelve cities; Detroit was keeping its expenses lower, in part, by selling water to the suburbs (and paying for freeway construction to the suburbs as well–thereby willingly facilitating, to a considerable degree, suburbanization which is a prime reason for Detroit’s present situation)12. Most of the twelve largest cities of 1960 Eastern America acted similarly–Detroit was by no means exceptional in this pre-1960 nurturing suburban relationship.

By the 1970’s, however, several large cities of the Midwest and Northeast were establishing metropolitan authorities or creating independent service districts for activities such as water and sewer (as well as airports and transportation systems). Boston created its Water and Sewer Commission in 1977 and Pittsburgh in 1984 (also Baltimore and St Louis (sewers only). Detroit did not. Anyway, the bonds, of course, for these pipes, sewers and water treatment facilities were/are Detroit’s and are presently rated Baa3.

The recently-released bankruptcy plan calls for the creation of a regional water authority. The proposed water-sewer authority would assume present and future debt and in return for leasing the city-owned water and sewer plants and pipes would pay rental or lease fees to the City. Presumably, the subsidy to city residents will go by the wayside–but the effect on the municipal debt burden is substantial and the water authority is a critical piece of Detroit’s fiscal solution. The reader should note, however, that water and sewer debt is not in default (although not without its issues) or is it really threatening to be in default. Water and sewer bonds are primarily revenue bonds, not general obligation bonds. Rather, the effect bankruptcy filing-resolution on water and sewer debt is to serve as the vehicle for the reform-rationalization of Detroit’s overall, long-term fiscal burdens. This, in our opinion, is a significant clue to the real purpose of the bankruptcy filing.

The bankruptcy filing, however, could have been used to do the same to Detroit’s Department of Transportation (the operating bus service which has 1500 employees). an enterprise agency which should be cost neutral to the city, but, in fact, is subsidized by Detroit’s general fund to the tune of $80 million in FY10. Most large cities have spun off the transportation function (Buffalo, New York, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, St Louis and Philadelphia, for example) to the county or to separate transportation authorities. Efforts within the three county metropolitan area to create a regional transportation authority were successfully approved by voters in the three counties (2006), but not by the city. So there is a suburban transportation authority (SMART), but the city operates its own bus system. We are not sure why this opportunity for fiscal rationalization is not included in the city’s plan–it is an obvious and key rationalization of the overall fiscal situation. Sadly, we suspect the politics proved impossible.

The Pension and Health Care Liability Crisis Of Detroit’s $18 billion in debt, almost half is pension and retiree health care benefit unfunded debt. There is a short story and a long story about Detroit and its pension-related debt. The short story is short–but far from sweet.

The reader ought to treat pensions separate from retiree health care benefits, legally the two are non-equivalent. Let’s take health care benefits, which are the largest single element in Detroit’s debt liability package ($5.7 billion) first. In most instances, Detroit and Michigan being included, there are no legal or constitutional requirements or prohibitions which compel a jurisdiction to honor a commitment made or included in a union agreement. Retiree health benefits are therefore unsecured debt and its fate in a future bankruptcy decision is likely to be very bleak indeed. California courts have already established some precedent in this matter–and those California precedents ain’t good news for the retirees. This release from annual required contributions to retiree health benefits, a considerable sum indeed as we have discovered earlier, is, in our opinion, the single most important incentive for the bankruptcy filing.

We confess this “lesson”–that retiree health care benefits–being largely unfunded in most American cities of any size13 may be the single most important “take away” from this discussion.

As to the $3.5 billion unfunded pension debt–that enjoys a completely different legal and constitutional status. The methodology by which the City of Detroit calculated this unfunded liability for the bankruptcy filing is unknown and the extent to which it can be included in a final bankruptcy decision is a “national” issue in that the Federal Court ‘s ruling which could set a precedent for all state and local jurisdictions. Now that’s the short story.

Now the long story. The real story about pension debt and Detroit’s pension program is less the unfunded liability than its management and its “political-labor negotiation” uses over its history. Did the city mismanage its pension debt is the more specific question at hand? Detroit was not regarded as having a particularly serious pension debt issue–although one is advised not to look too deeply into the books. A recent investigative report issued by a city-funded internal “watchdog IG-type unit” allegedly uncovered a host of findings, which, if correct, demonstrate consistent and persistent major deficiencies in the administration and fiscal responsibility of the pension governance and staff. The amounts associated with these deficiencies accumulate over the years into billions that should/could have yielded positive fund balances today.

Detroit has two separate pension funds; one operated on behalf of the police and fire departments and the second, essentially for the other municipal employees. As late as FY2000, Detroit’s police and fire pension fund was OVERFUNDED by over $620 million14. First, Detroit was by reasonable standards as late as 2011 paying over 90% of its annual required contribution (ARC)–anything above 80% is regarded as fiscally acceptable. The police and fire fund was funded at 99.9% of the ARC and the general fund at 82.8%15

If one looks a wee bit deeper, however, Detroit’s problems make one wonder how much longer it could continue to fund ARC at acceptable levels. For instance, in 2004 51% of retirement system members were working and paying into the system; by 2011, that figure had dropped to 39% (61% were then receiving benefits)–and with each worker laid off or vacancy not filled that problem would intensify.

Not well appreciated is the inverse relationship between personnel cutbacks made to reduce general fund balances in the city’s operating budget and a consequent increase in the pension fund deficit and a decreased ability to sustain acceptable level contributions to the annual required contribution. Maintaining the fiscal viability of the operating fund balance can have a zero-sum relationship with the city’s ability to pay the ARC. A 2010 PEW Report asserts that Detroit, in a boom year for revenues and stock markets, had to reduce its actual payment to 74% of the ARC16. In 2009 the courts ordered the ARC to be paid only after the police and fire fund successfully sued the city. In 2012 the city delayed payment of the ARC, owing the funds in 2013 over $103 million plus 8% interest17. Each year since the Great Recession, Detroit has gone through some complication in its ARC payment. Each year it reduces employment levels, the pension ARC is further compounded.

This inverse, zero sum relationship of municipal personnel employment levels and ARC is further confirmed by the 2013 reality that the ARC is the second largest single expenditure, second only to police and fire department expenditures, despite the significant reduction in police and fire employment over the last decade. Also, the overall effect of the city’s annual debt service (which includes interest on the $18 billion and the ARC) is that it presently consumes an estimated 46 cents of every dollar Detroit has to pay for its basic services18.

So Detroit’s overall pension fund annual payments seem fragile, and likely unsustainable in the short term. Has Detroit mismanaged its pension obligations over the years? Again, the answer is a qualified yes, but probably no worse than most large American cities. The 2008 stock market crisis cost the city nearly $1 billion in pension fund balances. The fund balances had recovered considerably in the post 2009 period as the market has recovered, but the reader must remember, the actuarial return on annual fund pension investment is usually set at 8%. Simply recovering lost funds over three years is commendable, however, the expected annual return on investment is most likely permanently lost–and, therefore, the long-term unfunded liability of the two pension funds has probably risen dramatically.

Ability to counter this loss with future returns is further compromised by the declining number of paying members and the ability of past and contemporary retirees in the general employee retirement fund to take a lump sum distribution at retirement–meaning the monies are not available for future investment. The Detroit Free Press, for instance, has reported that a city fiscal analyst found that nearly $2 billion had left the system since 2011.

Also, if we felt so inclined, we could harken back to a not too distant past (2005) and hint that previous questionable management practices, and failure to pay ARC required the City to borrow $1.4 billion to catch up. That $1.4 billion is now part of the general fund debt obligations on which annual interest payment will be made for the next twenty-four years. We could also mention that until 2011 a sweetheart deal with the unions traded off a pay increase in favor of a 13th month (essentially a bonus) and which substantially increased pension fund liabilities. There is also an issue with “socially correct” alternative fund real estate investments (estimated to be in the neighborhood of 10% of total investments by the two funds) by the two pension funds. The actual value of these investments is probably hard to measure and liquidity in time of need is questionable.

All of this more or less objective analysis is clouded by the bankruptcy filing’s estimation of a $3.5 billion unfunded liability. The source of the number is a report-analysis (by a consultant–Milliman) hired by and performed for the City’s new Emergency Manager, Kevyn Orr. The methodology underlying the number is unclear, may or may not be reasonable, and may, or may not, be part of the City’s negotiating strategy with the gamut of creditors in the bankruptcy process. It is apparent that Emergency Manager Orr has put in play unfunded pension liabilities which, if he sustains his present position, and achieves a favorable ruling from the bankruptcy court, could affect the “secured” nature of a pension contract–for every municipality in the nation. Just how this plays out over the resolution process may be one of the most salient (and interesting) facets of the Detroit bankruptcy.

Orr’s apparent plan to challenge the Michigan constitutional statute seems to state that pension obligations (or at least the accrued components of a pension obligation) are a contractual obligation that cannot be altered by a bankruptcy court. Since Orr has placed his suit in a Federal court and is invoking Federal bankruptcy law to force a restructuring of pension, obligations hitherto are considered subject only to state law. If successful, Orr’s strategy would have national implications. This too could be an element of the overall bankruptcy court process strategy.

Summary and Suggested Lessons

If the reader agrees with our analysis that Detroit’s bankruptcy filing was for the most part triggered by post 2000 fiscal management and the 2008 Great Recession, then the impact of politics on both (1) municipal governance and (2) fiscal stability is quite substantial. Legacy central cities with a fragile economic base do not have the luxury of incompetent or outright corrupt political governance. A legacy city with incompetent political leadership which exists in a state that has its own issues with its economic base (or presumably political incompetence or paralysis), the result can be catastrophic. Without competent, non ideological and honest political leadership, economic development strategy, in and of itself, is worthless.

So in our view the timing of the bankruptcy filing is most likely related to a political decision, probably heavily impacted by the Governor and Orr to deal with Detroit’s obvious insolvency now, rather than later. Since there will never be any good (or frankly even a “better”) time to go through this inherently horrible process, we defer to these decision-makers. Secondly, the future revitalization, whatever the revitalization plan may be, is to stop the hemorrhaging of taxes and revenues and establish some sustainable base from which new lenders and sources of revenues can be developed. In the present fiscal situation, anyone providing funds to Detroit has no real confidence that the funds will ultimately be used other than for stop-gap or worse purposes. Revenues for any future Detroit revitalization need a realistic security than the revenues will go where they are supposed to go and not be diverted. Bankruptcy is inevitable if a fiscal reset button is to be pushed and a fiscal reset is essential first step to future revitalization of the city. The recent federal $320 million “bailout” in our opinion, falls into the area of stop-gap diversion and media and political-electoral strategy. Also, the federal government can now say “we gave at the office already”–plus the likely reality that the bulk of the federal funds are not likely to be ever, never mind quickly, drawn down.

The canary in the Detroit bankruptcy filing “mine” are unfunded pension liabilities and, more importantly, an unfundable, non sustainable pay-as-you-go retiree health care benefit system. Both are national problems–and the latter is, in our opinion, the single most disruptive urban issue of the next decade. Economic developers take warning! The impact of these two fiscal time bombs in the next few years will be huge and NEGATIVE–really, really negative for most cities and counties.

The biggest single hole in Detroit’s present and future fiscal situation is retiree health care liabilities. The national municipal shame and dilemma that is associated with this issue is only now being acknowledged and appreciated. The more one studies how we currently handle and accumulated this massive debt obligation the more outrage one is likely to have. But the Curmudgeon will leave that to the reader to discover for themselves. It is likely, however, that municipal workers are not going to be happy over how this issue is going to be resolved over the next decade or so. Detroit is no better, nor any worse, than most municipalities on this issue–they are just among the first to deal with it.

The issue of Detroit unfunded pension liabilities has captured considerable media attention–and is likely to capture more. Fiscally, in the Detroit case, this may not be quite as important as we are led to believe—BUT…. please consider two points. First, how Detroit has proposed to handle its unfunded pension liabilities, if permitted by the Court (and survives certain appeals) will critically affect the larger context of municipal bonding (raising interest rates, reinforcing power of rating agencies–and even, in some cases, municipal access to finance markets). Secondly, the security to the pensioner regarding how much he or she will eventually be able to be paid in benefits received may well be lessened. Almost certainly the pensioner will get back what was paid into the system, but whether they will garner the full value of future earnings of the pension fund is more open to question. Thirdly, the extent of unfunded pension liabilities in many cities greatly exceeds any situation in Detroit. Bluntly, as the unfunded pension liability issue begins to be addressed, as it inevitably will over the next decade for sure, some municipalities will fail–or taxes will have to be raised to the point of a tax revolt and/or a serious decline in the level and performance of municipal services will follow. This is THE first and the PRIMARY crisis of urban America in this decade.

Unfunded pension obligations may have time on their side; unfunded retiree health care benefits for baby boomers is an immediate obligation and crisis. The lessons gleaned from California cities which have skirted around these issues (Stockton, for example) are bleak and harsh lessons indeed. Smaller cities, with less taxable resources, are going to be especially vulnerable. State receivership laws, where applicable (Michigan does NOT have such legislation) would help immensely, IF, the number and liabilities of municipalities did not reach critical mass. Those states that do not have a state receivership “option” in place ought to approve one quickly. The state receivership option may be the single most critical way the pension crisis can be dealt with without going through the municipal bankruptcy alternative.

Red sky at night–sailor’s delight. Red sky in the morning–sailor take warning. The dawn sky of many municipalities is red–and we do mean red (as in ink–and debt). Economic Developer take warning!

FOOTNOTES

1. Bryan D. Jones, Lynn W. Bachelor and Carter Wilson, The Sustaining Hand [Lawrence Kansas, University of Kansas Press, 1993]; and William A. Fischel,”Before Kelo”, Regulation, Winter, (2005-2006)

2. Fischel, p.32) also Ralph Nader and Michael Moore

3. Fischel, p. 33

4. During this time, while not without its problems, the automobile industry was fairly robust and car sales and worker salaries-employment were at their highest level–and would continue to go higher for the next generation.

5. Krugman, “Stranded by Sprawl” (NYT, July 28, 2013)

6. City of Detroit Annual Reports-cited in “Evaluating Chapter 9 Bankruptcy”, p. 4

7. Bureau of Census, City Employment in 1974

8. Budgetary revenue and expenditures cited in this section are from “Evaluating Chapter 9 Bankruptcy”

9. The water and sewer departments employ nearly 3100 (22% of city employees), twice as many uniformed fire fighters and closely approaching the 3300 uniformed police officers (FY2010 figures)

10. William H. Frey, Melting Pot Cities and Suburbs: Racial and Ethnic Change in Metro America in the 2000’s, Metropolitan Policy Program, Bookings, May 2011, p. 4; see also, Tim Brown, “Population loss in cities continued, with black flight latest trend”, Council of State Governments, May 2011

11. Budgetary revenue and expenditures cited in this section are from “Evaluating Chapter 9 Bankruptcy”

12. In 1960 Detroit’s Department of Water Supply provided water to a suburban population of 1.4 million as well as to its nearly 1.7 million residents. “If we had not developed the additional revenue (from the suburbs), the rates in Detroit would have been at least 41% higher” said the general manager of the department. He further added that “Annexation cannot be forced by creating a great thirst in the suburbs… A water utility should be concerned only with water supply and the protection of water supply”. Jon C. Teaford’s, the Rough Road to Renaissance: Urban Revitalization in America (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), pp.91-92 and John F. McDonald, Urban America: Growth, Crisis, and Rebirth (Armonk, New York, M.E. Sharpe, 2008).

13. “A Widening Gap in Cities: Shortfalls for funding pensions and retiree health care”, The Pew Charitable Trusts, January 2013; see also, Robert Pozen, The Retirement Surprise in Detroit’s Bankruptcy”, The Brookings Institute, July 25, 2013.

14. Detroit Free Press Editorial, August 23, 2013

15. “What’s the deal with Detroit’s mysteriously trebling pension obligations” Quartz, August 23, 2013, Table 1).

16. “A Widening Gap in Cities”, 2013 PEW Report

17. “How Detroit came to betray its retirees” Detroit Free Press, August 23, 2013.

18. Detroit Free Press Editorial, August 22, 2013.

– – –

Part II

The Economic Base and the Automobile Industry

The avalanche of articles and commentary concerning Detroit’s current plight often cite the population declines of Detroit since 1950 and then attach to these declines, the article’s favorite or thematic explanation for the primary cause. Judging by what the Curmudgeon has seen, the next most common reason cited is the collapse of the automotive industry. In this scenario Detroit, a one industry sector city which imploded on account of the collapse of the Big Three automotive industry.

We have some problems with this assertion and with the collapse of the automotive industry as the primary cause of Detroit’s bankruptcy. As the reader of the main article may have noted, the Curmudgeon’s critique of the role the auto industry played in the 2013 bankruptcy filing is that Detroit’s auto-related jobs were lost to Detroit over thirty years ago. Since 1950, the City of Detroit has lost 1,135, 792 jobs–338,087 (30%) of which were previous to 1970. In essence, a sizeable chunk of Detroit’s job losses were previous to 1970 when the auto industry manufacturing transformation and decline had not really gotten started. As we observe in the main article, City of Detroit’s auto-related job losses were quite heavier than its manufacturing losses in this period–the City auto industry job losses almost reached 70% by 1980. We take the position, that the post war job suburbanization is responsible for the City’s auto-related job loss- not the post 1980 Auto Alley. And since auto industry-related jobs in the City had been further decimated afterwards, there was very little left to lose by the time of the Great Recession GM-Chrysler bankruptcies in 2009. The 2013 bankruptcy filing was triggered by other factors.

But there is another interesting take on this issue. What is the relationship between central city population losses/gains to the overall metropolitan area manufacturing job growth/loss? To deal with this relationship we draw upon John F. McDonald [Urban America: Growth, Crisis and Rebirth (Armonk, New York, M.E. Sharpe, 2008), Table 4.1, p. 69], who, using census data and statistical abstract, compiled the 1947-1972 change in manufacturing employment and central city decline for the larger urban areas. Table 1 below presents that data for selected cities.

| City | (Urban area-1947-1972) Manufacturing Growth-Urban Area | Central City Growth |

| Chicago | 6.0% | -7% |

| Philadelphia | -6.0% | -6% |

| Detroit | -2.6% | -18% |

| Boston | -5.1% | -20% |

| Pittsburgh | -22.5% | -23% |

| St Louis | 8.0% | -27% |

| Cleveland | -2.0% | -18% |

The link between change in manufacturing and central city population change is far from obvious. For instance, St Louis increased manufacturing jobs and its central city exhibited the highest rate of population loss (even exceeding that of 2000-2010 Detroit). We know from hindsight that suburbanization and the riots of the sixties played the key role in population change in this period–not central city manufacturing decline (which actually begin during World War II) or the decline in the automotive industry.

To supplement McDonald, Norton in his landmark book, City Life-Cycles and American Urban Policy, offers a more complex rationale for central city decline, suggesting that “growth at the metropolitan level was the critical factor in the fate of the central city” of this time period. Norton posits that so long as the metropolitan area has job growth, central city population losses are moderated. In other words, suburbanization of manufacturing did not necessarily imply high rates of central city population loss.

To Norton, a slow-growing metropolitan area meant that the central city lost jobs and population. Jobs and factories were fleeing the aging cramped factories of the central city An urban area with a strong reliance of the old manufacturing base was a victim of the forces of change–creative destruction or the suburbanization of manufacturing. But those cities that could annex (younger and non-Northeast-Midwest cities) would retain both within their central city boundaries.

In short, following this line of argument, high pre-1970 central city population-job loss for Detroit was shared by those central cities which could not annex–or stated in different terms—most older, manufacturing central cities in the Northeast and Midwest. This issue for Norton was power/ability to annex which the Northeast and Midwest lacked. In essence the issue was not the geographic diffusion of manufacturing jobs (job sprawl)–but rather the political-legal ability of the central city to chase after them.

Suburbs are not necessarily the enemy. In fact, could it be that suburbs themselves can suffer from job loss? This appears to be possible given the persistent weaknesses exhibited by Detroit’s primary suburban county, Wayne County. The diffusion of the automobile industry to regions beyond even Detroit’s suburbs suggest that Detroit was placed in an even more precarious fiscal, economic and demographic position than is commonly recognized. Detroit’s suburbs have been in decline for quite some time. Accordingly, Detroit was not be able to draw any meaningful sustenance from its larger metropolitan area–which itself was declining.

The story is indeed complicated in that for some of this period, the state of Michigan was experiencing positive growth and employment from the auto industry. Citing the State of Michigan’s Michigan in Brief (Exhibit B: the Economic Base) which asserts that “during the upswing of the 1980’s wage and salary growth (in the motor vehicle industry) in Michigan exceeded the nation as a whole, but during the recession that followed (in the early 1990’s) so did the state’s job declines. The 1980’s then were not bad news, at least for Michigan. Michigan’s decline did not really take off until the nineties.

Since 1996 employment growth in Michigan has significantly trailed national employment growth. In 1970 Michigan’s share of US motor vehicle production was 31%. Michigan motor vehicle production, while volatile in recessionary years, exceeded 34% of all US production in 1982; by 1987 it had returned to 1970 levels (31%). After that year, Michigan started what was to become a serious decline, which stabilized briefly in 1994 at 28% before dropping to 20% in 2000. The Japanese competition and the building up of Auto Alley in the early eighties eventually severely impacted Michigan auto production at a point in time when Detroit had already been through the job and population wringer. The more salient issue is that when the City imploded in the post 2000 period, the state of Michigan had to cope with the felt-impact of a significant shift of the US auto industry to the Auto Alley. Michigan had its own problems when Detroit started its last decline.

Say it another way, the Michigan-based automotive industry did not begin its tumultuous decline until after the 1990’s. Using 1980 as our base year for serious automotive decline, Detroit had already lost 646. 238 residents or 58% of its post-1950 population loss. From the middle eighties, onward, but most critically after 2005, we freely concede that the auto industry played a significant role in Detroit’s decline by crippling or at least limiting the ability of the state of Michigan’s ability to come to Detroit’s rescue. That the decline in the auto industry directly affected the city fiscal situation, however, is a more difficult link. The impact of manufacturing employment losses was again “old news”. It may well have set the stage to some degree, but it did so more than thirty years previous. What was affected was Michigan’s ability to step in and soften Detroit’s decline.

Conventional wisdom holds the decline in the auto industry as the prime factor. Our analysis, however, suggest that Detroit was no longer directly tied to auto industry employment after the 1990’s. To be sure, Michigan was hugely affected by auto industry job losses–but not the City of Detroit. Indeed, to argue that residents left town and presumably moved to the suburbs (or anywhere) after losing their auto jobs would, at best, account for less than 20,000 population loss. Klier and Rubenstein’s in their excellent “Restructuring of the U.S. Auto Industry in the 2008-2009 Recession,( EDQ, May, 2013), for instance, makes no specific mention of the City of Detroit (as opposed, of course to “the Detroit Big Three”) and its being affected by that event.

“Motown’s” relationship with auto employment over the last generation or so falls into the legacy-symbolic category.

Comments

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.