Questioning Paradigms: Manchester England and the Plight of Legacy Cities

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

Stepping outside your home turf can reveal new insights. So off and on I read about the goings on in other nations. Recently, I started to read stuff about the United Kingdom’s economic development, a Growth Commission Report and a so-called “Manchester Model”. Much of my interest was stoked by my long-standing concern for Legacy Cities–urban areas, often in the Great Lakes, like Detroit, that are suffering through chronic, long-term decline and stagnation. Decades, indeed generations, of thought have yet to produce a plausible approach for their revitalization. Well, Britain is taking on its legacy city deindustrialization so let’s see if its helpful to us?

My reading stimulated a variety of thoughts and questions. Misery loves company so I thought I’d plague the reader with them.

Manchester and other northern UK cities share many of the same problems as our Northeast and Midwest Great Lakes legacy cities–they have lost a great deal of their economic meaning because of changes in logistics and deindustrialization. Deindustrialization is shared with other developed nations. I already knew that, but I always remained focused on America. One reason is I am very wary about transferring foreign experiences and economic development strategies lock, stock and barrel to the United States. We have a unique federal, two party-presidential political system, the oldest written constitution in the world, a multi-cultural society relatively open to immigration, and under normal conditions substantial internal mobility. All these factors are not just important, They are VERY important and should not be quickly dismissed.

But Great Britain shares our culture–and after all, we are related. And they subscribe to many of the economic development paradigms we use in the United States. Our economic development zone has British origins, for example. The UK is not a federal republic and its parliamentary system is very different from our presidential system. As a unitary kingdom (there are no states), local government is largely run by the national government. Whether or not that’s a great idea, a suburban American village of 10,000 souls enjoys considerably more local governance powers (budgetary, administrative and fiscal) and local autonomy than UK’s Manchester (500,000), supposedly the second largest city in the UK. That difference will explain why “political devolution”, the Brit’s phrase for empowering local governance, assumes such a prominent role in the revitalization debate. For us, that debate is an interesting contrast in that much of our debate calls for a more aggressive federal (national) government response and involvement.

What Am I Trying to Accomplish in this Review?

My starting point in dealing with all Legacy Cities is they need serious revitalization NOW. Legacy Cities are not only in economic decline–they verge on the edge of political crisis also. From the Beltway or the classroom, local and state politics is, well, “cute”, sort of like sausage being made. So let’s not think about it too much–rather let’s address the cold hard numbers and statistics of economic decline, apply our paradigm “du jour”, and make our case by discussing the obligatory, but hopelessly irrelevant, local examples of the paradigm’s application. Being the Curmudgeon, I bristle at this literature/blogs. They are so divorced from local realities that I find it offensive.

More than anything local revitalization is local. And in local government and economic development that means NOW, not producing results twenty years from now, not doing the politically correct things, but rather tackling known problems perceived as important by residents and tax payers. Algorithms and cost-benefit studies don’t cut it. Neither do long term theories and strategies. People want to “see” their local redevelopment–not hope for it. More than anything they need leaders, doers, who have integrity sufficient for resident’s and tax payers to trust.

My strategy is to approach local revitalization from its local context. At the local level, economics blurs with politics, ideology, culture, and past history. Residents define urban revitalization differently–economic development must serve several goals simultaneously. One cannot revitalize a Legacy City dealing with any one discipline’s goals or strategy. Local economic development in a crisis requires dealing with them in combination. Also, local revitalization requires local action, local decisions, local administration/ implementation–and a lot, lots of time to take hold. Earlier, during the Detroit bankruptcy debate, I wrote a review urging that Detroit stop “digging a deeper hole” as its first step in revitalization. That got lost in strategies calling for urban farming, urban forests, entrepreneurship, and the always successful innovation, creativity, and knowledge-based, data-driven economic development led by universities. The last set of initiatives and strategies are the paradigm I mean to confront in this review. Innovation, agglomeration, regionalism. university-led economic development and entrepreneuriusm are the cornerstones of England’s Growth Commission Report strategy to reverse it’s Legacy City deindustrialization.

As the reader might suppose, I am skeptical of the Growth Commission’s strategy. It did, however, raise my curiosity as to what the local governments there are doing to confront their problems. Does it bear any detailed resemblance to the solutions proposed by the Growth Commission? This interest seems very relevant in that simultaneous with the Growth Commission Report has been media commentary about the “Manchester miracle” or the “Manchester model”. Like Pittsburgh in the US, Manchester is touted to be a case study in successful urban comeback. OK–so what is it? Is it everything its cracked up to be?

I propose to discuss the Growth Commission Report , the “Manchester Model” and the problems they are intended to solve. But I will NOT TRY to apply it to the United States. Rather, let’s ask simple questions relevant to the American situation. The reader, hopefully, will make his/her own judgments about whether it will work here. The big, some would say huge, problem with this bifurcated approach is that there is a third participant in England’s Legacy City dialogue: the national government. Indeed, involving the national government is, to tell the truth, the most important element of the Growth Commission Report. But, being the Curmudgeon that I am, I worry that the national government has its own agenda–independent of any desire to solve the Legacy City deindustrialization. If so, I want to comment on that as well.

The first step in dealing with these tasks, however, is to set the stage–provide the background so our reader can appreciate the English context.

Manchester and the Growth Commission Report: Background

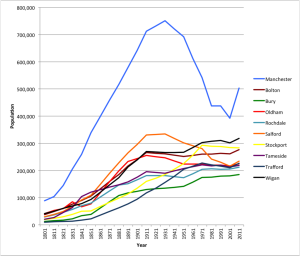

Manchester, the central city, peaked population way back in 1931 (766,000). In 2001 it had declined to its lowest level (392,000) since 1880 or so. Textiles were the industry that built the city–and that industry cluster is long gone–leaving in its wake hordes of lost jobs, empty mills, and neighborhoods filled with broken factories. After 2001, however, the city’s population exploded. The “central city” increased by over 87,000 or 20% from 2001 to 2011; Greater Manchester (the metro area) increased to about 2.7mm people (+7%). Other cities, Birmingham for example, have some decent statistics as well–so two questions (1) why Manchester, and (2) what’s going on. Why are we talking about the “Manchester model”.

The easy answer is the Manchester model has been embraced by the newly elected Prime Minister as one of his signature initiatives. Why did the Prime Minister climb on board with the “Manchester Model” economic development strategy? Up until the 2011 census Manchester and Birmingham both claimed title as the UK’s second city–but if this is a race, today Manchester is certainly ahead. Manchester has a “Model” for growth that the media like. Where did it come from?

Manchester seems to have benefited from a report issued by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce’s City Growth Commission (a year long inquiry into how cities can be empowered to shape and drive their economies) led by the well-known financial leader, Jim O’Neil. The Growth Commission is a think tank–it has no direct relationship with the City of Manchester.

The Growth Commission Report calls for the formation of a northern England mega city to which they give the clever name of “ManSheffLeedsPool“. Manchester is the first city named in the mega city–but the report itself, as I read it, does not single out Manchester–except that Manchester seems to highlight several of the reports recommendations. The report came out last year before the election. The “Manchester Model”, independent of the Growth Commission Report, seems to have followed a wonderful two page article by the Financial Times Jim McDermott titled “Manchester’s Second Coming” (2/22/2015).

The Growth Commission Report

The Growth Commission was financed by a group of British Think Tanks/NGAs, the Mayor of London, and various private equity and venture capital associations. The Royal Society, a 26o year-old “royal” think tank/foundation/academy is one of the most prestigious in the UK. The Growth Commission’s “commissioners” include Bruce Katz, head of Brookings Metropolitan Institute. My strong suspicion is the Commission taps into some pretty high-level Downton Abbey-type elites. The Commission’s principal non-policy objective was to inject its recommendations into the 2014 UK elections. It wanted to set the new government’s economic development agenda–whoever won. David Cameron, the winner and reelected Conservative Party Prime Minister, has gotten behind the report, endorsed key features and exposed it to national debate. His Chancellor of Exchequer (Treasurer/Budget) George Osborne said he wanted Manchester to be the engine of a ‘northern powerhouse’. That ‘s where McDermott’s Manchester Model enters the picture.

The Growth Commission’s Report is focused chiefly on (1) devolution of political and administrative power from the central government to local folk, (2) a fast train, and some (3) fairly high-powered academic/think tank economic development strategies (innovation, clusters, creativity). The Prime Minister and his Chancellor have piggy-backed on the Report and talk about creating a “Northern powerhouse”. what is this northern powerhouse? Osborne envisions creating an urban conurbation (a mega city) the size of Chicago. The mega city is to be forged by connecting four northern depressed metro economies by high-speed rail (Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds, and Liverpool). Importantly, Osborne has loosely agreed to devolve power to each metro region in exchange for greater cooperation among its metropolitan town halls. These semi-empowered regional entities would administer and coordinate the implementation of the Report’s strategy and transform their particular metro area into a growth machine.

If this worked as planned, the depressed northern urban metro areas would constitute a mega city with mega clusters of scale sufficient to innovate and attract investment competitive to those in the London metro areas. The idea is not to formally compete with the City of London (London is a contributor to the Growth Commission), but would supplement or compliment London. Zero-sum or not, agglomeration (mega scale) is the cornerstone concept underlying the proposed strategy to break northern England from the lock London seems to have on economic growth.

The formation of a competing mega city is necessary to confront, what I call, the UK’s “London Dilemma”. The London Dilemma is that London has captured a lot more than its share of private job creation, innovation, domestic and foreign investment, and population growth. Cities north of London have been left out of jobs and prosperity and have been legacy cities in chronic decline. What the Brits call the “north/south problem boils down to London being transformed into a sort of mega city and a socio-economic behemoth that threatens to pulverize the other British urban centers into economic ghost towns. The “North” is at best stagnant.

England has been divided into urban “have and have not” for well over a century (see How Green is my Valley). So the Growth Commission’s Report is far from the first word on the subject. “But it was in the second half of the twentieth century … that the economic gap widened”. The North became known as “the other Britain”. Since the Thatcher Era (the early eighties) politicians have promised to “rebalance” the economy. But between 2004 and 2013 for every 12 net additional jobs created in southern cities, only one was created elsewhere. so that in January 2015, the UK Centre for Cities concluded “the gap between cities in the south and cities in the rest of the UK has increased, not diminished“. This, in my opinion, is the problem the Growth Commission seeks to address–as we shall later discover, that is not the problem that the locals seek to solve.

The Commission Report proposes each northern metro, connected by a new rapid rail initiative into a northern mega-complex that will spawn economic growth which will “somehow” spread throughout its metropolitan area and thereby produce a metropolitan level revitalization–closing the gap with London. How?

According to the Commission Report, four cornerstone macro strategies will drive the revitalization: (1). Agglomeration or scale which is achieved by both railroad-induced “connectedness”; (2) an empowered metro-level leadership/coordination resulting from devolved powers/resources from national government to a regional government; (3) university and knowledge-based innovation and data-driven policy evaluation; and (4) non-defined programs in skills training, housing, and municipal fiscal/budgetary reform.

These drivers of economic growth, to me, lack the “horsepower” to achieve metro revitalization and close the north/south problem in any reasonable time frame. Housing may have some thrust, but skills training and university-led economic development are at best narrowly-focused and long-term affairs. Political devolution, however is the real engine behind both the national government and the Growth Commission strategies. Devolution’s benefits extend potentially to any number of policy areas, but if political devolution is tied to skills training and university-led knowledge-based innovation, I remain unconvinced that will unleash a “northern powerhouse”. These strategies are simply not up to the task of generating economic growth that corresponds to a Prime Minister’s electoral timetable. Perhaps, there are other agendas in play? What is this political devolution?

Political Devolution

Devolution of powers to Manchester’s Combined Authority (its regional government) has arguably been the most visible and most controversial of the three cornerstone assumptions. “(T)he UK, long one of the most centralized countries in Europe, is having a centrifugal moment“. (FT, Feb 22, 2015, p. 16). This is one area that Manchester does contribute to the Growth Commission Report–the Manchester metro entity has already put in place a devolution agreement.

By way of background, the Manchester metro area and its “regional coordinating body”, the Manchester Combined Authority, is composed of ten cities or boroughs. The Council of the Combined Authority, the borough legislature, is the central coordinating body for the Manchester metro area and in it are the ten mayors of the boroughs. The Combined Authority draws its powers, and most of its resources, from the central government in London. The Combined Authority is NOT a “bottom up” regional government, nor a city/county consolidation, or a “one stop shopping/marketing region. To me it more closely resembles an “urban county” as is found in the USA. Its powers, resources, composition, and most of its agenda is set by the government in London and Acts of Parliament. As such the Combined Authority has considerably less autonomy than an American county without “home rule”–it is close to the experience last found during the Gilded Age when state governments ran municipal police departments and approved street car franchises. Combined authorities ARE NOT even close to a metro government–even after a devolution.

The latest and greatest accomplishment of the Manchester Combined Authority has been its recent agreement with the central government, called ‘Devo Manc’. Devo Manc will transfer hundreds of millions pounds to the Authority, and, most importantly, create a new position, a directly elected mayor in 2017. Again, to me this compares to a directly elected county executive in an urban county–a significant reform, to be sure in the UK context. This is pretty rare in the UK and generates much comment. The point, easily lost in my background detail, is that a key element in the Growth Commission’s report is not yet in place–the Manchester election will occur late next year and start the year after. But the Prime Minister has brought home the bacon to Manchester–home base to his opposition socialist party. I’m sure the Prime Minister is acting responsibly with the intentions of a statesmen as he devolves powers to the Manchester’s region.

Limitations of the Growth Commission Report

According to the Report, political devolution is intended partly to address the current “fiscal gap” or budgetary deficits caused by welfare and social services/unemployment. Devolution, it is hoped, will increase local productivity, efficiency and innovation, resulting in prosperity/jobs created by the overall Commission strategy–and more tax receipts. Let’s hope this is the case, and that innovation will produce results to match the timetable. But absent new tax revenues, I would observe, the Commission strategy intends for the local folk to somehow find a way to overcome budgetary deficits that result from economic and social decline in these northern legacy cities. Correcting municipal fiscal and service delivery imbalances, even with augmented powers, doesn’t seem like an especially easy and popular thing to do at the local level. Universities can handle the creativity and innovation and mayors cut welfare benefits. Sounds like a deal to me. Having done his job, the Prime Minister has unloaded the burden of closing the fiscal gap onto a metro leadership dominated by his opposition political party–the Labor Party.

Connectedness or agglomeration is supposed to stimulate greater efficiency, creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship and knowledge-based economic growth. One supposed that one should plug in the normal Michael Porter synergies to explain how this absolutely must occur–in relatively short order to address the above fiscal gap. If such synergies fail to appear, or are not sufficient to close the fiscal gap, the local folk are going to have to figure out what went wrong. Now I understand how university-led economic development comes into the picture. It will be paid to do studies and prepare reports, based on data and databases they will develop. Here is the data-driven economic development called for in the Growth Commission Report. Any evaluation of policy implementation, however, given likely confusion of roles/resources and shared responsibilities among different levels of “government” and the ten boroughs, suggests to me a nightmare. Who and what is to blame will not necessarily be obvious. So I’ll hazard a guess that each university-generated evaluation and cost/benefit analysis will end up calling for further research and study. One certainty, however, is that the data-driven evaluation will not question the agglomeration/connectedness concept/strategy, but rather will focus on its implementation. I question the strategy–at least to the extent that it cannot be expected to produce results that match any reasonable political timetable or public expectations.

In short, I am suspicious that (1) the Growth Commission Report and its component economic development strategies are not up to the tasks intended and (2) the key reform, political devolution, is more of a trap for local officials than a holy grail. If so, the metro areas are going to have to generate their own growth, using their own strategies. At this point, it is relevant that we turn our attention to the so-called McDermott “Manchester Model” to see what the locals have been doing to create the so-called Manchester miracle. If there is to be any power behind the Northern powerhouse called for by the Prime Minister, it is not likely in the short term to come from the Growth Commission Report–rather it will be the locals doing it for themselves using their own set of economic development strategies.

The Manchester Model in Practice

To outline what has been going on over the last few years in Manchester, I offer a brief description.

Manchester has 96 city councilors, 95 are Labour (socialist) Party. This is one party rule. The city council’s chief elected official (sort of mayor, but formally President of the Council) is Sir Richard Leese. The rough equivalent to its city manager, Sir Howard Bernstein, is chief executive of Manchester City Council. Reese and Bernstein have led Manchester for two decades. The starting point for the Manchester’s current revitalization is alleged to be the 1996 downtown bombing, by the Irish Republican Army that injured 200 and caused an estimated $1 Billion Pounds (don’t ask) of property damage. Leese underscores any current success of Manchester to a very long-term effort and strategy: “Twenty years ago we realized that the decline of Manchester took 80 years; it didn’t happen overnight. So its rebirth as a modern, postindustrial city, again isn’t going to happen overnight. We plan for the long term“. (p. 16).

FDI, physical redevelopment (urban regeneration or urban renewal in Brit-speak), and large-scale, private housing development have been decades long economic development strategies pursued by Manchester’s leadership. In particular, a massive urban renewal program spurred or accompanied substantial private reinvestment and significant real estate development projects. Creative financing has also been an element. City of Manchester pension funds have been part of many a project’s financing scheme. The time lag from actual urban renewal demolition and clearance to private reinvestment and completion of projects has been considerable, however. Once the project is built, leased up, and open for business–it is treated as a success by most, including the media.

Foreign Direct Investment has also played a major role in Manchester’s comeback; Manchester is the UK’s second destination for FDI, after London. The key FDI “player”, Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi, bought the Manchester City Football Club in 2008. Subsequently, he invested one billion pounds to make the club competitive with its competitor, Manchester United. After that, the Sheikh’s “Chinese colleagues” (the Beijing Construction e Engineering Group) accumulated a 20% interest in the current Airport City development. Airport redevelopment is became yet another important element of Manchester’s revitalization. The independent, public/private hybrid authority, Manchester Airports Group, operates five area airports, and is two-thirds owned by the ten boroughs and 35% by Australian IFM private investors. Proceeds from the Airport Group are used to retire associated debt incurred by the boroughs on behalf of airport-related projects.

Leese and Bernstein’s economic redevelopment projects reflect Manchester’s time-honored economic approach. The”Manchester School of Economics”, built around free trade and economic individualism has served its present day revitalization very well. “Manchester, one of the first modern cities, was built on commerce and trade as much as industry. The liberal [what Americans would label conservative] attitude of the city elites later fused with municipal socialism to influence the activist, mercantile ‘Manchester Men’ that have governed the city council” (Alan Kidd, historian, p. 16). Absent are the words “neo-liberal” from Manchester’s socialist political lexicon. Manchester socialists are not struggling against capitalist elites, but rather work with them. This is a Manchester version of the luxury, two cities economic development strategy associated with Mayor Bloomberg and rejected by the current mayor. In any case, Manchester is one of only three large cities (Leeds and London) with a higher share of private sector jobs than the UK average.

Manchester’s regional government, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), is a relative newcomer, established only in late 2011. The GMCA includes the chief elected officials of the ten boroughs.The GMCA’s most effective contribution to revitalization has not been its substantial planning apparatus, but rather the political scale it can exercise as speaking for the region. This scale allows for improved negotiation with the central government, which can also serve efficiently as a conduit for central government deals, projects,initiatives and devolution. Leese observed that “Good politics matters more in places with bad economies“. (Andrew Carter, Centre for Cities, p. 16). The Combined Authority leadership did play a significant role in the consolidation/ merger that created the University of Manchester.

The Unspoken Ingredient for Successful Revitalization

To this point no one in the media or the Commission Report has mentioned what has to be a significant element of the Manchester revitalization, the dramatic and abrupt reversal of sixty years of population decline. Why, all of a sudden did Manchester attract significant population growth in the last decade? Remember, Manchester since 1930 declined from over 750,000 to less than 400,000 in 2001. Between 2001 and 2011, however, it dramatically grew by 87,000.

Twenty per cent growth over a decade does get one’s attention. The increase can be explained by the growth in the city’s foreign born population. In 2000 there were 142,000 foreign-born; by 2013 foreign-born numbered almost 334,000. In raw numbers alone, Manchester was second only to London in immigration from 2000 to 2013. Yet in media accounts, the Prime Minister’s press releases, or the Growth Commission’s report nothing is said about immigration and dramatic population growth. The word “immigration” is not found anywhere in the Report that I have in front of me. Immigration, largely of East Asians, is very controversial in the UK; its inclusion in a report designed for political action would be crippling. Still the injection of so many new residents in such a short period has to have some effect on the city’s revitalization; either this is one heck of a cheap labor force, a business climate delight, or the Asians are a source of entrepreneurism, and knowledge-based innovation–one or the other/probably both. Immigration, in my opinion, is the key catalyst behind the Manchester miracle.

Does Manchester’s central city growth spill over to its adjacent boroughs?

There is, of course, the fundamental issue that central city growth is supposed to flow over into the larger metro area. Has it? Surprisingly, probably because of immigration and physical redevelopment, the traditional paradigm of suburban growth and downtown decline has been reversed. Amazingly, this is not true only for Manchester, but for most of England’s Big Cities. “Eight of the ten largest cities in England have seen private sector jobs become more concentrated in their centers” (Centre for Cities, p. 17). So, Instead of America’s usual “hollowing out of the central core, England appears to be hollowing out its periphery. Still, “If Manchester is to become the London of the northwest, it will need the explosive growth at its core to radiate out to the periphery“.(p.17). What has Manchester done to address periphery decline?

Apparently, very little. On this subject a key member of the Growth Commission commented Manchester overturned the multi-decade regional policy of “redistributing money and public sector jobs to areas hit hard by deindustrialization. This is expensive and not sustainable in today’s fiscal environment. Instead “Manchester brings people to jobs instead of jobs to people” (p.16, Mike Emmerich, CEO of New Economy Think Tank). Private sector jobs that flowed from Manchester’s deals and projects have benefited principally the central city. Manchester’s strategy has meant spending money on tram lines, and its critics say it turns some suburban borough neighborhoods into commuter towns. Emmerich’s counter is “The unfortunate truth is that the alternative is that you are telling people they are going to remain poor.” If so, continued periphery decline does not bode well for the earlier mentioned hope that the northern powerhouse and would spur metro growth and address the fiscal gap caused by social service spending.

The Plight of Oldham

Let’s focus on one of Manchester’s suburban boroughs: Oldham (population nearly 100,000). Oldham has a long and distinguished history. One hundred years ago Oldham supposedly housed more millionaires than any other community in England. In 1900, Winston Churchill, a Conservative at the time, was elected from Oldham to his first term in the House of Commons. But those were the good old days. Today Oldham’s downtown “is looking pretty grim. Its 2001 riots were believed to be among the worst in English history. Today the community is further marred by segregation of south Asian and white natives. A British, far-right party received 16% of its vote in a recent election. In a 2008 poll, Oldham’s borough council “had the lowest customer satisfaction of any local government in England and Wales” (p. 17). Apparently one thing that Manchester has exported to its suburbs are poor immigrants. As for Oldham’s employed residents, they take the tram to Manchester.

Oldham is facing its own crisis. The Oldham borough leader, Jim McMahon believes that devolution has to be an improvement. To him the old system compelled each borough to humiliate itself so that it could compete for national financing— each borough had to make the case that its poverty was worse than its neighbor’s: “The way we were treated before by the central government meant we were almost rewarded for saying how desperate we were” (p. 17). “The challenge for us, McMahon argues, isn’t what we do for our poor people, it’s how we make sure we haven’t got any poor people“. To him this means embracing [the City of] Manchester. He hopes that Manchester development will spill over to Oldham, and a rising tide will lift all boats in the region. British policy academics, however, say Oldham’s day has come and gone. It’s time it’s residents to move on down the road–to places where there are jobs. How this fits into the Commission’s mega city context is anyone’s guess. McMahon fights back observing that “If Oldham is a place that just wants to manage its own decline, then its not a town that I want to raise my kids in“. (p.17). Confronting situations like this will be, in my opinion, an impossible task for the Growth Commission’s four-pronged strategies.

So McMahon refuses to go gently into the good night. He has reformed the borough’s social service administration, borrowed against projected future taxes, sold borough assets–and poured the proceeds into economic development. He upgraded town hall, provided grants to firms, sold borough land to investors from China and the USA. For the first time in years, property values are increasing in Oldham. The City of Manchester has chipped in with the Sharp Project, the revitalization of a large mill into a start up accelerator in Oldham. Having solicited and obtained private investment, Manchester Government (the Council) owns the Sharp Project. At the moment, it looks pretty sharp, but, let me say the obvious–it’s only one mill. In this context, start up entrepreneurs better grow fast and scale up soon–Oldham really needs jobs now, not good jobs twenty years from now. I

Time is the unspoken issue undermining the Growth Commission’s recommendations. All this rapid rail, connectedness, agglomeration and knowledge-based innovation, creativity and disruption strategy needs to come on line pretty quickly to solve the welfare crisis, ensure no more riots, end segregation, and eliminate the welfare deficit spending gap.

There’s nothing wrong with long-term good jobs in gazelle-like firms–but revitalizing a chronically declining legacy city, and improving the lot of its despairing residents is a “jobs NOW” kind of economic development. That might be working for Manchester, but much less so for her suburbs. Except for devolution, the Growth Commission recommendations have resulted in little more than media discussion. It is, as I suggested earlier, likely that devolution by the Tory government may be little more than a Trojan Horse for the northern cities of England.

Wrap Up

The debate sparked by the Growth Commission Report centers principally on political devolution which seemingly serves the political needs of the newly elected Tory government. The Growth Commission’s mega city, its high-speed rail connectedness, and its conventional, but tired, innovation/creativity/knowledge-based strategies demonstrate (share by gentry elites of both the USA and UK) seems largely confined to the Policy World and universities. Local governments in the UK, as in the USA, are pretty much on their own–and are following traditional economic development programs in redevelopment, foreign direct investment, with some start up and entrepreneur initiatives. The zero-sum competitive urban (UK) hierarchy does not offer much hope for overcoming the desperate and chronic decline of legacy cities as each of the troubled UK legacy cities will copy the same agenda. Deindustrialization–which comes down to the loss of a community’s economic meaning–is not likely to be reversed by high-speed rail induced agglomeration. Unless, of course, innovation and knowledge-based jobs, not to mention creativity, travels best on fast rather than local commuter trains. More likely, these economic development strategies are just a sop for the gentry liberals and academics. The key uncertain dynamic for UK cities, however, is immigration. Immigration obviously negatively impacts each city’s fiscal imbalances, requires sustained social service programs, but may well facilitate increased foreign and domestic investment. The metropolitan dilemma, i.e. can central city prosperity spread across boundaries to address suburban decline, is simply unknowable at this moment.

At its core, deindustrialization results from the maturing and collapse of clusters and agglomerations. Innovation, creativity, entrepreneurism are perceived remedies which, if successful, can either revitalize old and tired clusters, or build new ones. There is nothing wrong, in my opinion, with attempting to build new clusters in deindustrialized cities–but the reality, for me at least, is that considerable doses of serendipity, and pure luck accompany such a strategy–especially when nearly every other city is following a near-identical approach. In any case, rebuilding or building a new cluster takes time–lots of it. In the meantime, the traditional second wave economic development approach has the merit of providing a visual reassurance to citizens and tax payers that someone is doing something to help out.

Comments

This is an excellent account on the Manchester Paradigm, thanks for this one. I once blogged for a London-based economic strategies group known as New Start, and I would say that British views re: “economic development” is like comparing apples to oranges in comparison to U.S. perspectives.

The Brits are more inclined than us to mix public sector terms with private sector terms, but not by much. When this factoid is brought up in my circles, no one seems capable of understanding the significance of this distortion; it’s like upsetting the applecart — the private sector drives public sector deals. But where are the corresponding public goods? As a consequence, we only have the Chamber of Commerce model in the public sector.

What both the U.S. & the Brits have in common re: their understanding of “economic development” is that both seeks ways to only promote business development, using heavily subsidized public funds. We get regular reports of “economic growth” here and “development” there, but structural poverty remains. Concentrated poverty continues to go up, but we don’t have leadership which even acknowledges the problem, except that “they need to work longer hours”, in the words of Jeb Bush.

The primary focus must be upon socioeconomic outcomes, whether it’s in the U.S. or the U.K., with an added sense of urgency. It’s far past time for us to have a new paradigm ourselves, but that would require an intellectual revolution in the entire planning profession; hope springs eternal.

Comment by Fernando Centeno, CED on July 26, 2015 at 7:58 pm

The comments are closed.