Breaking Up [Paradigms] is so Hard-to-Do

By The Economic Development Curmudgeon

A New Way to Think About State and Local Economic Development

Through the Lens of Forgotten People

The following article begins to make the case for an alternative way to “do” economic development at the state and local level. President Trump’s challenge, however one feels about him, is to confront the problem swept under the rug by innovation, knowledge-based economics, university-led economic development, and “gazelle” clusters and occupations. Contemporary ED says train for a gazelle job (skills training)/occupation, go to college, become an entrepreneur, or relocate to where the warm sun of free trade shines. Forgotten People who can’t, or won’t, compete in that game want and need something different.

Current strategies, dominant now for decades, obviously haven’t satisfactorily addressed this problem, and there’s no reason to think they will anytime soon. The likely default responses will be: more of the same, doubled-down, combined with huge doses of “targeted” “redistribution, fiscal stimulus, “big” infrastructure, more skills retraining. Dominant paradigms characteristically resist change. Admitting there are no magic bullets, I believe we can do better than more of the same. But “better” involves thinking differently. It isn’t simply announcing “this” or “that” strategy or program is needed. Rather, the first order of business is to understand who we want to assist—and discovering ourselves in the process.

A good part of the Forgotten People problem, as I see it, is “socio-economic class”. We ignore class as we design our ED strategies and programs. Less obvious is over the last couple of decades, ED policy has more and more been devised by academics, researchers, and Think Tanks. Whatever they are, they are not focusing on working class Forgotten People. Predictably, our solutions for them are to be like ourselves. Be creative, go to college/graduate school, chose the right occupations and industry sectors. The problem seems to be that Forgotten People can’t or refuse to be like us. They also seem to want different things out of life; they want different lifestyles; they value other priorities—and fears. Many consciously do not want to be us. Paranoid, they may or may not be, but the system doesn’t work for them—and they know it.

If we want to work with Forgotten People, we might want to understand them, know what makes them tick, what they want to do. We have as a profession gotten too smart for our britches. We don’t qualify for middle-class anymore; we increasingly possess graduate degrees, we think in concepts, ED plans, research studies and algorithms. Value-wise we look at the world through a lens that reflects images more like Downton Abbey than Studs Terkel (bet you don’t know who he is). We can’t assist people we don’t understand.

Read on as I peddle my anti-intellectualism to make the case American state and local ED should learn not only how to talk with working/lower class Americans—but offer them some realistic economic opportunity acceptable to them. Before we devise strategies and programs we might better understand and appreciate the values, attitudes, goals and priorities of those “we plan for”.

Breaking Away from Current Paradigms

Because becoming just like us ain’t working! And it ain’t right either. All people have a right to define their own lives and values. Our job is to deliver economic opportunity to them as best we can. Our task is not only to foster the “creative” in creative destruction—but to assist those affected by innovation’s destruction.

That, I believe, means we might want to develop a new economic and community development approach, with new strategies and programs— new goals with a working/lower-class clientele.

In the remainder of this issue, I outline an initial, exploratory outline for how we can develop an alternative approach to dealing with those hurt by creative destruction. It does not reject, but rather departs from our “usual suspects” strategies, choosing instead to venture new ideas and refresh some older ones. These ideas are meant as suggestions for state and local ED/CD—putting the macro-Media free trade/productivity/protectionism/Ryan ‘border taxes’ to the side.

Thomas Kuhn–Master of Paradigm

By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33728444

The new approach contains new mixtures of Mainstream business-centric ED and community development. The new approach envisions a conscious decentralization of policy implementation to local communities, including small city, Big City, rural towns, and suburban. The role envisioned for state/federal levels are to provide financial resources and supportive legislation. Our approach empowers local communities to assume responsibility for dealing with Forgotten Peoples. It assumes communities will forge public/private partnerships to bring in the private sector into program design, implementation, and funding. Finally, our approach redefines Forgotten People to include females, Blacks, Chicano/Latinos, immigrants—to embrace all working and lower class households that are motivated to improve their situation.

There is nothing easy or automatic about any of these assumptions.

The new approach advocates the following directions and operating tenets:

- includes Forgotten People in design and implementation, tempering ED expertise with acknowledgement of the values and priorities of a socio-economic class that differs from our professional class;

- provides different, but complementary, opportunities and paths for Mainstream ED and community development;

- shifts ED’s almost exclusive focus on manufacturing and technology to include service/retail and sectors;

- emphasizes community-level infrastructure (away from rail, highways and bridges) to “pipes”, flood control, housing-related modernization, affordable housing, environmental cleanup, community modernization (demolition), community beautification, and quality of life upgrading—using local workers/businesses;

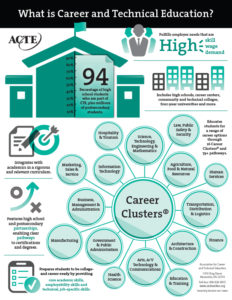

- requires “hiring” “motivated” Forgottens who commit to work/training programs, stresses workforce training in partnership with private sector/unions, less university/college–focused than high school and vocational, local occupational deregulation, combines work experience with remediation/basic skills training, and includes auxiliary services necessary to training success;

- urges development of a distinctive strategy for middle-age Forgottens that includes provision of auxiliary services such as child care, working poor tax/benefit solutions, etc.

Picking Up from the Last Article

Last time out, the article introduced my concern with the Forgotten People plight/crisis—a concern made apparent by President Trump’s victory. The article traced some pre-election macro-economic discussion that enlarged the definition of inequality, questioned whether current innovation, sector/occupation gazelles, disruption, and knowledge-based economics paradigms were all they claimed to be. The paradigms’s reaction to the concerns raised, my article suggested, was to advocate more of the same, and reiterated the “usual suspects” ED strategies listed above.

The above strategies (in some form and combination) have been pursued by most cities and states since the turn of the 21st Century. Innovation and knowledge-based economics, as well as gazelle-chasing (sectors, forms, and occupations) are rooted in, if not an evolved response to, dysfunctions attributed to mobile capital, comparative advantage, deindustrialization, runaway firms, and free trade. These strategies resulted from the 1970-2000 Great Reindustrialization Debate–a debate which so-called neo-Keynesians mostly won. As such most cities and states currently are following ED strategies that are intended to overcome the negative consequences of free trade, etc. The overall thrust is to create innovative new industries (and occupations) that can effectively compete in the global arena. Sunset or declining industries, firms and occupations are mostly to be left to their fate–the “usual suspects”, geographic relocation and skills retraining for growth occupations/sectors are the traditional response to this dislocation.

The justification for this strategy is that neo-Keynesian paradigm asserts innovation, and the new gazelles they create, will produce more—and better—jobs than they destroy. That they haven’t is alleged to be the basis for President Trump’s victory. In any case, whatever jobs have been created, they have left behind millions of unemployed and underemployed, falling labor participation rates, dramatic declines in productivity,and chronically-distressed cities like Detroit that are permanent features of our urban landscape. Moreover, generational-based issues question whether our younger workers can find jobs—even with huge college debt and degrees. The fact that unemployment is at such low levels raises the question of whether that statistic really means what we think it means?

While many suggest the neo-Keynesian model is no longer working well (and we need a better model), for the moment it appears neo-Keynesians are still in charge—and to the extent they are not, opponents turn to a limited protectionism which, if faulty, will seemingly make the problem of Forgotten People worse. The basic issue is “destroyed” jobs in sunset industries leave households, families and individuals behind in clustered places/communities, locked in working/lower class prison that cannot provide a reasonable income, lifestyle, and for those that want it, escape. For decades, whatever new jobs have been created leave large numbers of these folk clustered in chronically-depressed communities, neighborhoods, and ghettos.

In my last article I presented my reason why all this wondrous state of affairs exists; I called it lag and shift (L&S). L&S takes no position on whether free trade, more precisely comparative advantage, creates more jobs or not. What it simply says is those who lose jobs through disruption often do not find new jobs or jobs that pay as well. Instead, new jobs occur later, as much as a generation later, and they go to the flexible young who want to move about to get away from the family unit. Dad and Mom, divorce, stay behind, wait on tables, say hi when you enter Wal-Mart, and retire early. Those children that stay behind in the old family homestead find few opportunities, with or without a college education, and so we have our industrial heartland voting for Trump.

The strategies economic developers currently pursue either reject L&S, ignore it, or simply, and implicitly assume a sort of occupational survival of the fittest in which, of course, they are the “fit”. Get a college degree, get a “good” job, and get the hell out of dead cities and move to the “creative” (entrepreneurial, innovative) ones. Well, … dead metropolitan areas apparently vote. Amazingly, a current “reform” is to change the constitution so that the electoral college no longer provides an opening so that dead cities can vote for change. Rather than that, I hope economic and community development can positively respond to those dead cities and Forgotten People.

“Class” Rears its Inevitable Head

Everybody these days seems to agree that “inequality” exists and is getting worse—President Trump included. But solutions, measured by media ink and digits, are minimum wage, tax CEO pay, access to toilet seats by oppressed minorities, reform of police departments, “safe spaces”, “trigger warnings”, and elimination of for-profit schools. The focus on higher education as the path to employment is challenged by realities that most who attend college don’t graduate in six years, require serious remedial effort to supplement high school learning, and leave behind a huge student debt legacy. Free college education is now touted as the new answer—that will improve access, but can quality and seriousness be maintained? Maybe this “college” strategy isn’t working all that well. Near universal higher education is not proving to be the quality “base’ for the knowledge economy.

Inequality at its root is a “class-based” concept. The Forgotten People were, and are, mostly working-class, lower middle-class. Those unable to economically function become lower-class. They live in the same neighborhoods and subdivisions. The current stereotype lies somewhere between Hillbilly Elegy, Wilson’s “When Work Disappears”, Murray’s “Coming Apart”, and Eberstadt’s “Men without Work”. As a solution, our current economic development paradigm proposes to transform the Forgotten People, our “lumpen-proletariat”, into a middle and upper-middle “knowledge-based and creative” class where, as Garrison Keillor might suggest, “everybody is “creatively” above-average”. The insurmountable barrier to this utopian task, I (and others) suggest, is certainly who pays for it, but also something called “culture”.

Class is not just economic; it is social as well. Classes come with their own culture, value system, sub-groups, and way of looking at things. If we as economic/community developers are middle/upper-middle—and the Forgotten People are not—we have to bridge a social-economic (cultural) chasm if our strategies are to succeed.

Throughout its history, nineteenth and twentieth century American economic/community development understood that its ultimate purpose meant providing opportunities and quality of life for the working and lower classes—to prevent revolution (and unions) and to keep them “in the system”. Assimilation is what they called it and it was a gradual process that took generations. Assimilation meant more than a job—although that was central—it meant a quality of life, family, and sufficient hope to inspire motivation equal to the task of achieving economic mobility. Assimilation required personal commitment and a long and winding road before success. This is so out of style today. At least in the professional classes.

Today, however, identity politics rejects assimilation and, in the process, creates categories of preferred oppressed groups and groups that oppress them. The problem, it now seems, is the Forgotten People fall into the latter category. Identity politics, by definition, is not especially class-based. Instead it focuses on media-inspired “groups”whose members are victims of a crushing, oppressive system—in need of salvation. And then there are the oppressor groups whose often unconsciously values and actions do the oppressing. This is the essence of our “culture war”, a war that has displaced the culture that supported incremental assimilation—the war that redefined individual mobility from economic to political. That redefinition of economic mobility to political solutions minimized the importance of economic and community development. We took our eyes off the ball of lower and middle-class economic mobility and confined our efforts to redress the adverse consequences of globalization to the “usual suspects”.

The culture war, however, has taken an extra step which has further hurt ED/CD. Intersectionality (which asserts that identity oppression is magnified by an individual’s multiple identities (being lesbian, transgender, Queer and racial minority means each individual’s repressed identity compounds/worsens the others) creates a new hierarchy of the “deserving poor” and a list of culprits who made them poor and oppressed. The culture war became more complicated. The Forgotten People have been included as a group which oppresses minority identities. Today many Progressives are now at war against Forgotten People. Instead of being oppressed themselves as lower/working class, Forgotten People have become the oppressors personified. Defined by the media as Trump’s electoral constituency, the Forgotten People, the “Deplorables”, are the oppressors. How can economic/community development support these Deplorables without hurting oppressed identities?

This is a terribly bad start for economic developers. Much of the problem is we have allowed the media to do our thinking for us and they have defined the Forgotten People incorrectly—and restricted policy attention to free trade/tariffs and an erratic protectionism. From my perspective, the media, by adopting the perspective of identity politics, has displaced the more relevant, more useful notion that economic/community development ought to assist the lower and working classes become, over time, more upwardly economically mobile. If Forgotten People are a socio-economic class, they are not the identity group portrayed in the media. To attack the problem one might rethink who the Forgotten Peoples are?

Most of us would probably agree a critical reason for the Forgotten People is the decline in manufacturing, and the rise of knowledge-based technology and low-paying service sector—now threatened by automation, productivity, and robots/drones/artificial intelligence. That is the real job killer—less so comparative advantage or free trade. Still each has done its part to create a dichotomous society and workforce which no amount of economic/community development can bridge. We might toss out the notion of oppression and oppressors to remove the divisions that inhibit any effective ED/CD attempt to assist a redefined Forgotten People.

Our first task is to figure out who the Forgotten People are My prism is socio-economic class.

Forgotten People aren’t Only White (ethnic) Males

Forgotten Peoples are a socio-economic class (working/lower) that includes females, all points on the sexual continuum, Blacks, Hispanics and countless ethnic/religious immigrants who live scattered across the jurisdictions, neighborhoods, subdivisions and ghettos of America–as well as the media-defined white, male Deplorables of the industrial heartland.

Numerically many do not work in permanent jobs—and likely never will. An increasing number are not even counted as members of the labor force. Most did not vote—for anybody. But if President Trump is to be successful in living up to his Inaugural Address, he has to find a way to assist the totality of the Forgotten Peoples, not just the ones on the National Mall. Personally, although I recognize many will not agree with me, I think he is just fine with assisting the totality of Forgotten People. He talked about inner cities, rural areas and industrial heartlands.

Inequality, in America and elsewhere, is inherently rooted in its socio-economic class structure. Class is not exclusively Marxist or socialist concept. Class is an objective element of any ideological system, capitalist, socialist (look at Cuba, Brazil, or even France), or even feudal. I personally am a capitalist—and hence am probably a Deplorable to many.The identity culture war should not stop Progressives from trying to help those Forgotten People which they are devoted to helping. Mainstream, business-centered economic development and community, people-based development each has a role to play in assisting the Forgotten People. The person of color in an urban ghetto, the Chicano barrio, and white rural small town, former working-class industrial neighborhoods, not to mention the suburban working/lower class all are Forgotten People. That classes are divided by race and ethnicity is nothing new. They always have been. So, economic developers choose your definition of Forgotten People and let’s get to work.

Bridging the Cultural Chasm

First let’s set up some ground rules and guidelines for understanding and opening up a dialogue with Forgotten People, understand the implications of our current strategies and how we/they might think of future strategies.

Make no mistake, we (economic and community developers) are not Forgotten People. I come from deep blue-collar roots, but in no meaningful way am I working class. I am quite well-off if income statistics, career pattern and Ph.D.’s are a guide. I do not speak for the Forgotten People—they are a memory for me, a fond and respectful one. I am surely paternalistic, certainly perceived as such, even if I don’t want to be. I need to listen. I should not assume my paradigm is theirs. Unless we want to decide for them, impose our solutions on them, we want some kind of buy-in. We want to be sensitized into their goals and values. Our strategies will work all the better if we minimize the “they” and “us”. Can this be done?

Yes. Consider Alinsky, an Depression/WWII-era community development leader, who is well-respected in our professional lexicon. His famous community mobilization strategy rested on confronting problems identified by neighborhood residents themselves—not that Alinsky identified. Alinsky worked with the Catholic Church, unions, business, and politicians-whatever it took. The point is economic developers simply must invest time and effort to figure out how to include these folks in their plans and be flexible in making decisions such as the design of programs, and goals for strategies/programs. Stepping outside our paradigms is a prerequisite if this effort is to be worthwhile. We can no longer require Forgotten People to “be like us” and pursue careers, retraining compatible with our paradigmatic, knowledge-based sunrise occupations/industries.

Community development might move beyond identity politics and social empowerment. Economic developers might include initiatives that put aside the “good” jobs and occupations in favor of those attainable and wanted by Forgotten Peoples—even if they are “dead-end”. Maybe we should use Forgotten People jobs to improve the communities in which they live—to install community physical infrastructure, to forge more resilient human infrastructure, and to address the quality of life in our cities, towns, villages.

Several Potential Strategies to Stimulate Thought

This article concludes with four ideas, meant to stimulate thought–as much about the approach taken as about the specifics. They question whether knowledge-based solutions that stress higher education, technology skill sets, and primacy of “good” jobs in “growth” clusters/industries. These ideas are all community-level based and each require financial support from higher levels of government to go anywhere. Admittedly, these suggestions reflect my perception of “where Forgotten People are at”. But someone has to start if the discussion is to occur.

- Let’s be realistic in our goals. Working with the Forgotten People does not mean every single one of them. Our focus here is with those who want to change and are willing to work hard to find employment and skills. It is not our job to motivate. Nor does it mean our initiatives permanently solve identified problems. Statistical compliance with “paper” goals matters much less than “word of mouth” and visible change in status/mentality. In the good old days, progress was measured in lifetimes and generations. Motivation and willingness to work are absolute essentials to any ED/CD program. Because an individual, household is “deserving” is not sufficient.

Career plans should be realistic; entrepreneurial ideas should undergo their own “shark tank” process. ED can help those who want to be assisted and who are willing to step up and do what it takes. Subsidized employment programs should not be based simply on descriptive criteria (or identities), but “hired”. If its redistribution you want, send the client to welfare and food stamp programs. If drug rehabilitation is part of the employment process, and the Forgotten Person steps up to the plate.

- Manufacturing enjoys a great multiplier; technology a great future so they become the holy grail for ED. But the former has matured, and the latter has started down that path. Each will produce fewer employment opportunities in the future–and those they do require very sophisticated training. For many Forgotten People, they are no longer realistic opportunities. Instead, a serious challenge would be to apply entrepreneurial, startup, workforce training and traditional mainstream ED programs to service sector, retail, car repair, health/personal care, and housing-related professional firms (electrician, carpentry, roofing, plumbing, heating, landscaping). These skills and occupations are vital to community upgrading and are more familiar.

New firms compete with older firms, and subsidized cost provides an unfair advantage). Still service and retail sector entrepreneurial programs, if planned with existing local companies, might work wonders. Can the reader imagine a “restaurant accelerator” in which middle-age displaced workers open up in a nonprofit facility, with a shared liquor license, common advertising and purchasing, startup ovens and kitchens, all in a decor attractive to consumers, that permits a new culinary entrepreneur to see if he/she is cut out to run a restaurant?

The easier approach would be to return to the old vocational school, apprentice, and work experience programs of the past. There are reasons why they have fallen out of favor—including poor image, opposition from unions, regulation of professions, excessive safety requirements, lack of mentors, and many others. Today ED assists the “correct” manufacturing and technology startups, computer-software related occupations—all of which are more technical—and earmark as “growth” and reasonably paid occupations. Apprenticeships, guild-like supervised training by these private firms could offer younger workers a real chance. It works for manufacturers and technology companies, but vocational-related service firms are another matter. It takes imagination and, frankly courage for an economic developer to attempt programs in this area—but they may prove to be the most successful and of high demand.

- Program design should consider the need for “auxiliary” services relevant to the program. If not available, viability of program is seriously threatened. Child care, subsidized education, transportation, health care, tax implications for working poor rectified. Families used to handle these matters, but most contemporary families possess sufficient capacity to function as in previous decades.

The working/lower class culture in particular is visible testimony to the collapse of the American two-person family. That economic development does what it can to restore the functional equivalent of the old-time family is now part of our job—just like it was for settlement workers, housing reformers, and neighborhood revitalization. Auxiliary services can provide employment opportunities. That business can play a vital role in this should be assumed. They are part of the “who is going to pay for all this” problem.

- Employability is a major issue for many Forgotten. Forgotten Peoples are not saints. They are human beings not endowed with any special holy attributes and, like you and I, have every failing literally-known to mankind. They make mistakes and mistakes have consequences. Work discipline, soft skills are critical, and corny as it may sound, character-building should be an element of program design. Basic skills remediation, basic skills, GED, ESOP, and the litany of existing programs remain essential to Forgotten People work-related ED strategies. If at all possible these initiatives should be directly linked to employment and actual work.

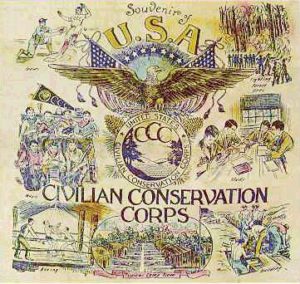

The linking of work, remedial and vocational education, and basic and soft skills training makes these initiatives local government prerogative (even if funded by higher level). In the old days, individuals were given a choice between the army or jail for a variety of reasons, but one was the army provided discipline, soft skills, and basic occupational training in one package. My model, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and to a lesser extent the Work Progress Administration (WPA) were New Deal cornerstones intended to put workers back to work. In my view, they accomplish the same purpose, while providing a host of small-scale, community-based improvement projects that can, along with a remedial and basic skills component can cut through the nexus of employability issues.

Potential projects range from neighborhood cleanup and improvement (trash/car removal, environmental cleanup, painting, demolition, park maintenance, trail-blazing, and state and local nature and tourism development). For more advanced skill workers, local brownfields cleanup, subsidy for volunteer firemen, and labor on local sewer and water pipes, small flood control projects, and a variety of spruce up projects can restore aesthetic appeal to tired small towns and villages, as well as the toughest ghetto. This is best described as “Back to the Future” economic development.

These ideas will no doubt face tough sledding in a profession and policy area that is resistant to a socio-economic class and unable to develop a two-way communication relationship. For all the ED planning, board of director “inclusivity”, public hearings, perception of our “expertness”, and belief in the infallible correctness of our paradigmatic strategies has allowed us the luxury of effectively leaving Forgottens outside of our deliberations. I hope we can challenge these ingrained tendencies and work to find ways to address chronic underemployment and falling labor participation rates, especially in our chronically declining cities/distressed neighborhoods and rural areas by actually including those Forgotten People in strategy formulation and program design/implementation.

Comments

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.