Early Republic MED Context and Strategies

The Formative Years of the Early Republic (1790-1870)

Population Migration, City-Building, Cultural Diffusion: the Early Republic Big City Paradigm

Those who have read Theme 1 modules understand the 19th century Early Republic and Gilded Ages especially were the periods in which the foundations of American MED were laid. Population migration, diffusion of political cultures, city-building and (in forthcoming modules) the centrality of industrial manufacturing and infrastructure were MED’s core strategy nexus or paradigm. The first three are the subject matter of this module.

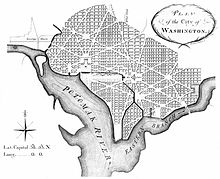

That all this is largely a post-1800 phenomenon is probably surprising to many readers–our history textbooks smush all of this into a description only faintly reminiscent of what transpired. In this brief module, I try to demonstrate how the these ED drivers (population migration, cultural diffusion, city-building strategies jelled into a Big City MED paradigm from which Big City MED evolved. My plan of attack is to first describe city-building. America’s first major city-building effort, was Washington D.C., part of a comprehensive developmental infrastructure strategy, was advocated and achieved by now President George Washington, our self-declared first economic developer. This module in part describes what was Washington’s signature project as an economic developer, and to ignore timelines and cut across themes/topics to describe this project, almost literally to Washington’s deathbed. We will return to both timelines and topic areas in the next module.

In presenting our case study of Washington D.C., I am frankly more concerned with city-building as a strategy and process than with extended discussion on building a “national capital“. We have already described the “why” behind its location; while not without its potential economic meaning to Washington himself, that decision was primarily political. To be sure one cannot ignore the fact that the city in question was intended, in its way, to contend, it not compete with places like London and Paris–but also to compete with places like Philadelphia and New York City as leaders in an emerging American urban hierarchy. One cannot ignore DC’s function of unifying the nation–in fact that accounted for why D.C. existed at all. National capitals have certain prerequisites of which its famous grand boulevards and Greek-style hallmark buildings are only two. But I have other purposes in this module.

First, I want to describe city-building as an economic development strategy, and as a process extended over time, institutions/EDOs, and people, which inevitably encompasses other ED strategies to accomplish its purposes. Also, Washington D.C. was a singular exception, a national-level economic development strategy, and it will deviate in important ways for the more private, or semi state-level city-building described in our future modules.. Surprisingly, under Washington’s fairly direct supervision, he was after all President, it is much more private, congruent with the state-level city-building than one might imagine. We are particularly interested in how the President’s DTIS strategy fared in the near-decade he personally led this project. We will ignore timelines and follow that theme to his successor, Thomas Jefferson and see how the latter’s image of Washington D.C. prevailed over the former. Secondly, my goal is to link city-building to larger macro-ED strategies, in particular DTIS (developmental transportation infrastructure strategy) and economic base development. These are the paramount paradigmatic Early Republic ED strategies.

A 19th Century constant, the century’s core ED paradigm was DTIS. After the Civil War the “D” dropped out of the TIS, and that radically shifted the dynamics of the paradigm–a story which is still a long way off from this module. In the Early Republic modules, however, the “D” was critical to understanding the dynamics behind policy-making, the EDOs utilized, and a major factor in accounting for the disparate regional development that evolved in the course of this Era. As the reader reads this module I ask she keep in mind that Washington D.C. city-building led by the President is a central element in the the Era’s initial use and future development of that ED strategy-paradigm was very much “developmental”.

The President was literally creating a major port city from a swamp along a major river. That is a hazardous enterprise whatever the Era, and in 1790 one might keep in mind American finance and industrial capitalism was still a babe in the woods–so put on hold your sweeping notions of capitalist power and greed. The story that will unfold will, if nothing else, demonstrate the fragility of early American capitalism. Its failure results from its excesses, but also from an early decision by the U.S. federalist Congress not to provide direct federal funding in the construction and development of its own future capital. It left that almost entirely to the dictates of state-level incentives and the desperate, almost pathetic efforts of aggressive capitalists, such as Robert Morris, to amass private capital to finance the basic infrastructure and initial investment in a swamp to make it a city. Let me clue you into the future–it essentially did not work. The Congress that “let George do it” had its reasons.

That failure, I hope you will accept, demonstrates the need for a viable public-private economic development venture. In the 1790’s Washington D.C. example, the EDO was indeed public-private, but the financing structure was not. The federal government (Congress) played a negative role almost setting George Washington up for failure so that his project would fail and the national capital could be relocated elsewhere. The ongoing political polarization between Federalists and the D-R was not the cause–George Washington and Thomas Jefferson worked cooperatively on the project, despite their vastly different visions for the future “city”. Rather, the project was starved for federal monies. The Residency Act provided NO federal funds for the acquisition of land, the provision of infrastructure, or for the construction of the government’s public buildings, including the Congress and White House. The Act merely authorized the President to accept grants and “requests” as the means to finance all these functions. In essence, the Congress declined to invest its own funds, such as they were in 1790, to the development of the national capital–and capitol. It left the financing completely in the hands of private investment and such other revenues as were available [99] Stanley Elkins & Eric McKitrick, the Age of Federalism: the Early American Republic 1788-1800 (Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 173.

What will be less obvious is that the private financing did not work well,not only because of the excesses of its capitalist investors, but also because foreign direct investors (FDI), the only viable source of long-term private infrastructure financing, could not overcome the barriers engendered by the European world war that was raging. Without that infusion of FDI capital, American investors in 1790’s Washington D.C. city-building were probably doomed to ultimate failure/marginal success. In 1790 American capital accumulation was too dependent on wilderness land speculation–which BTW was the first step, as messy and destructive as it was, in settlement/homesteading of the West. The pre-1800 collapse of American private financial investment system inhibited western movement as well as city-building.

The dirty little secret behind any American ED/MED/CD strategy/program/paradigm is somebody has to pay for it. Sometimes we tend to think of economic development as a rational policy based on expertise or professionalism. The reality is that economic development floats on a sea of politics–driven by cultural chasms–and by who pays for it–and that reality does not disappear if it is conducted by a government because the government too must pay for economic development as well. Follow the money (or the lack of it) is a good rule of thumb in ED. The reality of project financing is the public developer, burdened by time and fiscal pressures, does not possess the full-range of opportunities and resources theoretically available in hindsight or better judgment. The EDO is limited to those opportunities that, however they get there, appear on its doorstep. As the old adage says: you play with the cards you are dealt. All the rest is kibitzers. If we accept the assertion by Elkins and McKitrick, and I do, the parameters of city-building authorized by Congress in the Residency Act doomed the enterprise from the start:

Endemic to the entire undertaking was a lack of money. The [implied] decision to rely principally on land sales was, in effect, to restrict the source of funds from the outset to a mere trickle. It would in turn be necessary t deceive Congress in reporting progress … All of this meant formally committing the Executive and the entire government to a policy of minimal financial support. Thus the Executive should he subsequently want to try to reverse that policy, and ask Congress for money, would incur a full review and risk a jettisoning of the entire enterprise [99] Stanley Elkins & Eric McKitrick, the Age of Federalism, pp. 174-5

Also city-building (or its lack) resulted in regional urbanization or non-urbanization. 1790 Census data reported 24 cities/towns whose population exceeded 2,500 (an aggregate of 200,000 population). By 1870 there were 683 cities/towns above 2,500 (aggregate 9.9 million), and by 1890, 1351 with 22.1 million residents. By 1990, there were 8500 towns and cities greater than 2500—187 million[vi] There was an awfully lot of city-building going on in the vast expanses of continental North America, and it started very early after 1790. City-building, the most primeval and arguably the centerpiece of MED strategies, is the most unappreciated, yet is the most fundamental in understanding the behavior of its core institutions, political culture and future political life.

Where to Locate the Nation’s Capital

It All Starts with the Residence Act

Where to place the capitol of the United States was a really big deal to the new Congress. Few Congressional delegates were very happy that New York City, the last of a series of “wandering Articles of Confederation capitols, was the first for the new Republic. They quickly started debating the issue in 1789–and after a series of bills, some of which were approved, the entire process bogged down and came to a crashing no-result conclusion by the end of the first session of the First Congress. Bordewich claims “that no other issue that had come before Congress [to that point] had produced the same frenzy of backroom bartering and vote trading” [22] Fergus Bordewich, the First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (Simon & Schuster, 2016), p. 148. The formal debate commenced in the last days of August, 1789. In that early debate lots of locations were proposed, but three (1) Pennsylvania (in or near Philly mostly), (2) New York City, and (3) Virginia were the most prominent. Philadelphia (or its adjacent geographies) was the early front-runner. The first session debate was most elucidating, dispelling any naive belief that regionalism (they called it sectionalism) mattered little in federal policy-making. The Federalist “Two Region” dichotomy broke apart into four or five major geographical fissures, in which the state delegation was a major unit in policy-making. Distrust as much as rivalry among the regions was evident, and it was easily apparent that national patriotism was a mile wide and an inch deep. Congressional Representatives thought in terms of their particular State and secondarily their “section”. High among their motivation for acquiring the nation’s capitol was the economic benefits it would undoubtedly bring to the State or urban area.

Washington, for a variety of reasons (poor health, reluctance to intrude into Congressional deliberations) took a back seat. It was probably just as well, because the frenzy of proposals produced constantly shifting alliances and vote trading that defies any attempt to briefly summarize it. Two dynamics emerged early, despite a powerful New York delegation, nearly everybody else wanted out of the city–to almost anywhere else; only New England offered any level of support. The South, in the first session especially, suffered a serious setback when advancing its interests, it triggered a substantial push back caused by an unrelated debate on “outlawing slavery and at minimum restricting the slave trade, that was generated by a grouping of Pennsylvania Quakers that descended on Congress’s Federal Hall in considerable numbers. Acting much like a formal interest group they pigeon-holed Congressional delegates and promoted the introduction of several bills and formal debate simultaneously with discussion on the nation’s capitol. Stretching alongside the debate on the nation’s capital, the debate on slavery gathered its own momentum during August and September, 1789.

Rising to the floor was Massachusetts representative Thomas Sedgwick, who in 1780 had defended in court an accused slave woman, Ms. Mumbet, who had escaped from New York to Massachusetts. He argued successfully that she was not a slave by Massachusetts law. As a Freed Slave Woman she entered into his employ in Stockbridge–and defended his property when it was attacked by Shays insurgents in 1786. Her future great-grandson was W.E.B. Du Bois. In the midst of the slavery debate, Sedgwick observed that the South’s claim to be the nation’s most populous region, and thus deserving the site for the national capitol, was largely based on its slave population. That was absurd he argued “that men who were merely the slaves of the country, men who had no rights to protect, being deprived of them all, should be taken into view in determining the center of government. If they were considered, gentlemen might well as estimate the black cattle of New England” (this was meant as sarcasm) [25], Bordewich, p. 151. Bordewich asserts the issue of slavery, swept under the Congressional rug to that point, was now brought to the fore and the “odious distinction between Northern and Southern interest [could] create a party spirit which will be carried into all other measures“. [26] Bordewich, p. 152. The slavery matter, despite the best efforts of proto-abolitionist Congressional Representatives did not result in legislation, and most of the Federalists (including Washington off to the side) wanted the matter off the agenda in fear it would destroy any hope of effective policy-making on other matters.

Into this moral morass stepped James Madison. A participant of the Patowmack project, he had already bought into Washington’s conception of a new Potomac city as the port city of a Virginia canal into the trans-Appalachian interior–and as a national capitol with a geography “neutral” to North and South. On September 4th, he laid out his ideas on the Potomac site as the preferred location for the nation’s capitol. He argued that the Potomac site could integrate the soon-to-be-settled trans-Appalachian west the best of any of the proposed sites. It was ” the great highway of communication between the Atlantic and the western country” [22] Bordewich, p. 150. It would be the least vulnerable to foreign invasion (was he wrong on that one, 1814). He was vague, very vague, as to the precise site, implying it could be in territory close to today’s West Virginia. Madison was supported by Alexandria’s (the proposed port city of Washington) Congressional representative (Richard Bland Lee) who played bad cop to Madison’s good, by asserting that his Potomac site was the ONLY site that could produce and maintain “a perpetual union and domestic tranquility“–a none too obvious threat that tied the future of the federal union to one location only. He further offered the observation that up to this point the South as a region had not gotten much out of this Congress, that New England, New York and Philadelphia had benefited unduly, and it was now the South’s turn for favorable legislation. If not successful on the residence matter “it would be an alarming circumstance to the people of the southern states” and a negative decision on the matter “would determine whether the [federal] government is to exist for ages, or be dispersed among contending winds“. Get the Drift? [22] Bordewich, p.151.

Slavery had permeated Residence Act discussion, and seriously polarized both houses of Congress to the extent that southern slavery was used to justify a non-southern location or discredit a southern one. In turn, southerners, more unified than ever as a coherent bloc, were deeply resentful of Pennsylvania (with strong Quaker traditions, the state with the most Free Blacks, and Philadelphia’s immoral capitalist/merchant leadership, personified by Senator Robert Morris). The South effectively was transformed into a not too subtle bloc against front-runner Pennsylvania in the latter’s quest to acquire the national capitol. Pennsylvania’s drive to be the national capitol was led by none other than our Senator Robert Morris. In his mind, as in the mind of his close friend the President, this was an economic development initiative–Morris asserted the Susquehanna and Philadelphia were the more natural and powerful avenue into western trans-Appalachians. Philadelphia, already home to logistics firms, major investors, and the Bank of North America was ideally positioned to serve as the export port of the nation–the economic and hopefully the political capitol of the United States.

Truth be told, Washington had apparently convinced Morris of the merits associated with a state-driven developmental transportation infrastructure strategy when combined with a simultaneous settlement-city-building strategy. In 1789 Morris and others formed the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Improvement of Roads and Inland Navigation. Morris became its first President. The Society immediately turned to the State of Pennsylvania for state financial assistance “in the interest of internal trade, manufacture, and population of the state”. There was no time to waste he argued: “the state must act quickly lest the channels of trade go elsewhere, and even though our route be the natural one, enormous expense will be required to restore the channel of trade to us once it is forced [i.e. if competitors establish first advantage] [77] Joseph Dorfman, p.284. Morris proposed a robust private-public partnership in this quest to use transportation infrastructure to open up the trans-Appalachian west. Combining both roads and canals, he called for state-chartered corporations in partnership with state government to pursue individual projects, financed by equity, bond issuance’s and state aid. The Legislature agreed and quickly empowered three internal navigation state-chartered corporations, which were all chaired by Robert Morris. He rapidly asked for direct financial assistance from the state–which was declined–but did allow liberal provisions for the raising of equity–lotteries. It is worth note that while these projects got started, none were completed to the extent that they achieved, even in limited substance, the goals. That, however, is another story. What is critical at this point was that Morris and Washington/Madison each had virtually identical competing projects/strategies, intended to accomplish DTIS/western settlement goals, which would be anchored by the national capitol

Since House action was constitutionally necessary before the Senate could consider the matter (appropriations were involved), the House took the lead in negotiations, forming its delegation into a voting bloc. What followed was a series of double-crosses as New Englanders, Patowmack advocates, New Jersey, and New York House representatives made deal after deal, one overturn the other. In the course of those “deals” different Pennsylvania sites were advanced, splitting the Pennsylvania delegation. The negotiations became so noisy, and the topic heavily reported in the local Philadelphia media, that the House gallerias filled up with interested observers. Finally in mid-September, the House voted to approve the “seat of government” at “some convenient place on the east bank of the Susquehanna by 32 to 19. Three commissioners were appointed to select the specific site, purchase the land, and within four years construct the federal “campus”. In the meantime the capitol would remain in New York City. Southerners principally offered a series of amendments that were defeated. The Patowmack site was effectively dead. And the matter moved onto the Senate.

To advance the cause in the Senate Morris than donated $100,000 on behalf of the State of Pennsylvania to construct federal buildings in Philadelphia–shades of the Amazon HQ.But then the roof fell in. Pennsylvania’s other senator, a western populist (William Maclay) immediately attacked Morris and Philadelphia’s bold incentive-offer as little more than an attempt by its merchant elite to attract “a few barrels of flour” and observing their power was so great that he feared “it was probable these vile arts {the incentive] will prevail“. Truth be told, Maclay favored a Pennsylvania site outside of Philadelphia or its immediate suburbs. Maclay reported in his diary that “there had been a violent schism between [Morris} and he Pennsylvania delegation, at least a part of them” [22](Bordewich, p. 154. Apparently, the wounds of Pennsylvania’s bitter bank and populist war, less than two years in the past, had not healed. Morris, predictably, entered into a blitz of deal/negotiations designed to secure approval for a Philadelphia suburb, laced with personal and public incentives, and trading votes with non-Pennsylvania Senators. The matter came to a head on September 24. In a series of consecutive motions, described below the matter was finally “settled” after nearly a month of off and on debate and maneuver.

Maclay [started it off] by moving unsuccessfully that Morris’s proposal be ruled out of order. Next, the Virginians proposed … [replacing Philadelphia] with the Potomac. Another motion called for planting the seat of government on the Susquehanna in MARYLAND. Morris than reiterated bis offer to provide $100,000 if the capitol went to Germantown (Philadelphia suburb). When the votes were finally tallied on Morris’s motion … the Susquehanna was struck out leaving a blank … [which] Morris immediately moved to insert Germantown [22] Bordewich

In the next ensuring vote on Morris’s motion to insert Germantown, Maclay voted against Morris’s motion, resulting in a nine-nine tie–with Vice President Adams having he deciding vote. Maclay who had previously publicly characterized Adams [presumably in a tweet] as “a Monkey just put into Breeches“, after a long series distracting comments, voted for Morris–citing Morris’s $100,000 incentive as the reason. Who says incentives don’t work?

Philadelphia’s suburbs won its bid to house the nation’s capitol, despite having been sand-bagged by its own Senator. But a few days later, James Madison offered a final amendment to the approved bill. The incentive and the state-donated free land for federal buildings were paid for by the State of Pennsylvania, he observed, Didn’t that mean the land and buildings belonged to the state government? How would the federal government acquire the site–the motion was silent on the matter and needed to be completed in order to complete the transaction. That seemed logical to a Senate majority who, in the rush to adjourn the session, voted by a majority of one to carry over the bill into the next session when a final vote would occur. Morris, confident the final outcome was secure, went along with the vote. Madison, however, had other ideas. In the meantime, the session ended and everyone headed off “to the beaches”. As Massachusetts Federalist Fisher Ames commented at the time “And thus the house that Jack built is vanished in smoke” [22] Bordewich, p. 157.

While Congress was in a three month interlude, returning only on January 4th, 1790, newly appointed Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, was toiling at his desk, preparing a report which he was to formally submitted to Congress of January 9th. That report, cleverly entitled “Report on Public Credit” proved so disruptive, controversial, and yet so critical to the future of the new Republic, that it forever changed the agenda of the new session, and sucked the political air out of its deliberations.

George Washington the Midwife of Washington D.C.

If the reader has no stomach for conflict of interest in politics, than better skip this section. If the reader wants to think of George Washington cast in pure marble on a pedestal, throwing his dollar over the Potomac, and never seeking personal gain please barricade yourself in the safe room. If there was any doubt Washington saw the capital, and its location as a furtherance of his Patowmack Canal project–along with his vision of national defense and hinterland settlement as the only path to national survival–and both congruent with his desire for personal wealth, than this section should answer any doubts. Did Washington have larger “preserve the Union” motivations? Yes, I believe he sincerely did–but they all were smushed into a mental blender that, given the period’s ill-defined conflict of interest values, its blending private and public in ways we no longer understand, never mind tolerate destroys any aura surrounding city-building and ED, and emits if anything a bit of “odor” not too pleasing to ones senses. Forgive me when I say, get used to it. It doesn’t stop with George.

Congress in the Residency Act entrusted the project, its basic decisions, and its implementation–development to George Washington, the President. That Act established a “federal district”, and created a government commission (agency) to operate the project–empowering George Washington to appoint, not nominate, its membership. Washington quickly appointed to the Commission (1) the administrator of his personal business affairs/personal doctor and the husband of Martha’s daughter; (2) a former Maryland Governor who had nominated Washington to the position of commander-in-chief of the Continental Army back in 1775; and (3) the district’s former Congressman, who had switched his vote on the key Assumption of Debt legislation in favor of Hamilton, and was Montgomery County’s largest slave-owner, who personally owned 4000 acres within the announced site. The EDO, government or not, was Washington’s personal creature–and although it was government in structure, its governance was thoroughly private sector. Oh, and did I mention that all three commissioners were members of the Patowmack Canal Corporation Board of Directors–the last member described being President/CEO of the Corporation [99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital (Amistad/HarperCollins Publishers, 2008), p. 63.

It was Washington’s intention these fine and dispassionate folk would carry out the day-to-day decision-making of the federal commission–with himself as Chair. Yes, as described in an earlier module, Washington personally owned land within the district as well[v]. 63.? Whatever the politics associated with the Congressional decision-making that placed the location of its capital in a swamp, targeted by Washington’s (and Jefferson) as a potential port city for Virginia which so badly needed one to extend its economic and political influence into a trans-Appalachian interior, the reality of the city’s economic vision was tightly linked to the the Patowmack Canal DTIS project. Washington was very faithful in fulfilling the political vision, a national capital that might compete with European capitals, the unifier of a divided two-region nation, and a very defensible strategy for national survival in a hostile world– but Washington’s economic vision for the city left little doubt that it was Virginia’s opening salvo in what was to become a half-century of state-level competition to cross over the Appalachian Mountains and construct an urban hierarchy in which that state, if not dominant, would unduly prosper from.

The Residency Act set very broad geographic parameters–extending deep into today’s West Virginia–for the specific location of the city, which was to be determined by none other than George Washington “hisself”. After a long trip into the federal district hinterland Washington specified the site (January 24, 1791) as being from the village of Georgetown (Washington’s hoped for manufacturing base) to the east bank of the Anacostia River–exactly where he wanted it in accordance with his Patowmack Canal long-term plan. There was one problem with the specific site, however. The original Residency Act did not cross over the Potomac, and so it excluded the “other bank” which included the key port city of Alexandria. So an amendment to the Residency Act was submitted to Congress.

The amendment included, besides the city of 3,200, ans 1,200 additional acres owned by Washington, 950 acres owned by John Parke-Custis (Washington’s step-son which subsequently became the future Arlington Cemetery), as well as several developable lots in Alexandria proper owned by Washington. None of this was a secret–it was well known to Congress [99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 64 . The amendment was approved, although it did exhibit its own interesting politics.

Accordingly, an amendment to the Residency Act was filed in mid-February by Charles Carroll, former Maryland Governor and owner of huge tracts of Potomac River land–in the middle of Hamilton’s national bank debate. The amendment got caught up in the politics of that bill, and for awhile it was uncertain, that if the President voted for the national bank whether or not a revenge motion would not only defeat the amendment, but repudiate the Residency Act as well[vii]. . This may, or may not, have entered into Washington’s soon to be told “Ten Days That Shook Economic Development” in a future module. In any event. Hamilton got his bank, and Washington got his amendment, and Jefferson and Madison got really, really mad. In later years, after Washington died, none other than our second president, John Adams, commented the amendment raised the value of the acquired properties by 1000%. [99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 65 . Just saying … For those aware Alexandria is today an independent city in the state of Virginia, Alexandria became so only in 1861 when it joined Virginia in seceding from the Union. In the meantime it and the lands leading to it were part of Washington D.C.

With Congressional approvals in hand, a government EDO at his service, and surveying by Andrew Ellicott quickly completed, the architect/city planner (Pierre L’Enfant} was hired in January 1791. Leaving L’Enfant to his designs Washington appeared in person on site on March 28 1791 to personally manage the project. Oh Well. Having been briefed by L’Enfant on his plans (see below), Washington proceeded to negotiate the Commission’s purchase of the private land directly with the eighteen major landowners within the district. He struck a deal with seventeen of them, leaving one outstanding. Owned by a curmudgeon Scotsman, David Burns, Washington negotiated with him for several months (finally shamed him with patriotism and overwhelmed him with his status as President): “The pain which this occurrence [the disagreement] occasions me is the more palpably felt, as I had taken pleasure during my journey [to D.C.] through several states, to relate this agreement, and to speak of it, on every proper occasion” [99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 55 Burns eventually gave way to the President’s logic–but held out for several months, and finally agreed with the proviso that only a public building would be built on the site (the White House sits on that site today).

The negotiated “deal” was that the owners would “pool” the individual titles into one aggregate title which the federal government would purchase at a fixed price of $25 per acre. The area would be subdivided into lots by L’Enfant, with one half retained by the Commission to sell to the general public or use for streets and public buildings; the other half would be given back to the original owners at no cost. If additional acreage were required than $66 per acre would be paid for them. Thus the federal government would use only half the acreage for public buildings, public squares and roads and revenue-raising land sales. The other half (potentially improved by infrastructure and development) would be returned to the original landowners at no cost—a sweetheart deal by anyone’s estimation.

With the exception of Burns, Washington secured their agreement in one day and evening [vii] also .[99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 75. Sweetheart deal it might have been, but the government got its share of the sweetheart as well; the government acquired over 10,000 lots, miles of street at no cost and no time-consuming, legally pioneering eminent domain. and 500 acres reserved for public use for only $36,099. The existing landowners were in on the deal, benefiting from its success. That might have been competitive with Peter Stuyvesant’s deal for NYC.

Washington’s intent was to sell portions of the public area to private owners, raising the revenue to construct the public buildings, for which Congress had not provided funds to construct or develop. Washington seemingly believed a flood of landowners would eagerly bid up the lot prices at the auction, and thus yield the desired for revenues. But he also took safeguards to limit absentee land speculation and “flipping” and required “brick”, not wood (prone to termites/rot) for any improvements. Talk about the “art of a deal”. It sure looked good in March 1791.

Shootout at OK Corral: City-building 1791

Washington, little experienced with design and the aesthetics of city-building assigned the review of L”Enfant’s sketches and designs to Thomas Jefferson [1119] his none-too-happy Secretary of State. Jefferson on his own dime, in Philadelphia, prepared his own image of the new capital’s design: a “federal village” of just twenty blocks (Foggy Bottom) intended to be an austere “farmer’s capital that shunned the pretensions of Europe, based on a simple grid [99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 73. This did not square with L’Enfant’s vision, image and elegant designs and broad radial boulevards extending great lengths into the district [99] Elkins & McKitrick report “he was “well-pleased” with it when he finally received it in August 1791, but also acknowledged he had earlier sent to L’Enfant his own drawings and thoughts on the matter p. 173.

But returning to March, Washington, on site, was briefed and given the full-court press by L’Enfant on his private designs and plans–to which Washington seemingly concurred. L’Enfant’s grand vision as well as the specifics of the Plan, however, was not communicated to existing landowners, who thought more or less along Jefferson’s vision–and, amazingly, was not revealed to the Board of the Commission. The grand radial plan with exquisite public buildings, so admired today, was kept in secret between L’Enfant and Washington until Washington compelled its publication to prepare for a second land sale in late summer, early fall. The expansive concept and designs, however, were only one aspect of L’Enfant’s opposition. He resolutely did would not accept that land sales would (1) work successfully as the the project’s chief revenue source (the lots were in his view essentially worthless); and private development on these lots were ultimately conflict with the grandiose and expansive designs and city pattern he proposed. L’Enfant believed financing (lacking federal funds) required the issuance of debt by the corporation–which in fact proved to be correct. The divergent approaches, so basic to finance and city vision, were not reconciled by Washington in this time period. Decisiveness was not lacking in Washington–as general he displayed it consistently–but here he kept his options open.

The first public auction (October 17, 1791) was scheduled to sell the first lots. Washington, Jefferson and Madison were present at the auction, but had to unexpectedly leave just before bids were heard in order to get to the opening of Congress in Philadelphia. The land did not sell very well. The auction, scheduled to last for three days, ended the first afternoon. Only 1% of the expected sales, about 34 lots, were actually sold–raising a mere $2,000 in cash. The three illustrious attendees, themselves purchased four of the lots to jack up interest in the bidding. L’Enfant got the blame–for several concerns on his activities thus far, but the most outrageous deficiency was that he he had not even provided a map on which the lots were drawn and visible by the time of the auction.Washington was more than mad, complaining how could anyone ” be induced to buy … a pig in a poke”[99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, p. 85 .

Ironically, today L’Enfant is regarded as a icon on urban planning and design–over time the city would be built along most of its basic outlines. But in 1791 it was hopelessly out of style with both the mechanics and financing of American real estate, and the visual images, wide expanses, and grand flourishes of his plan were not only too expensive for a Republic literally in near-bankruptcy and just commencing its debate on its first national bank–but more importantly were out of touch with the “royal” or “Roman” grand image L’Enfant was attempting to create. Perhaps instinctively, L’Enfant had kept his designs, plan, and lot subdivision hidden. Literally only Washington had seen them. While the failed auction, as we shall shortly see, triggered a Valley-Forge like-crisis in Washington’s project over the next year, L’Enfant continued to refuse to reveal publicly his plans until February, 1792 when forced to by Washington.

In a visionary vacuum before and after the failure of the first land auction, Washington’s handpicked government commission fragmented, and when seeing L’Enfant’s implementation of the Plan became skeptical, if not hostile. Landowners factionalized into pro L’Enfant, anti-L’Enfant–and they distrusted the Commission. Washington in one instance had to return to D.C. to restore their order, and bring Burns into the fold. L’Enfant, to complicate matters, could brook no compromise or incorporate other perspectives, it was his highway or nothing–despite the reality the Board and landowners still had no idea of what the Plan included.

Worse, the architect plans did not square with the commission’s (lack of) budget or the non-existent Congressional funding, property lots would have to sell at prices that grossly exceeded the prevailing price. The sale of these lots to the general public was the Board’s future revenue source to finance the City’s construction of public buildings, required by the Residency Act to be completed no later than 1800. If not completed the project authorization would cease and a new location would be decided by Congress. As the Commission saw it in 1791, the only source of cash was the incentive grants made by the States of Maryland and Virginia–less than $200,000 (Virginia $120,000 Virginia, and $72,000 Maryland)–promised but with no legal time-schedule for disbursement. Someone was heading for a bruising. It was the fiscal situation that compelled the resolution of the internal conflicts as the Commission essentially ran out of money and stopped construction and laid off the work crews.

If this were not bad enough, L’Enfant refused to cooperate with the Commissioners, proved uncooperative with the Ellicott, the surveyor, and unbelievably, forcibly tore down a building of a very rich owner (November 1791) because it violated (slightly) his hidden plans. That he had trespassed and torn down construction on a private lot was flagrant enough, but, he refused to reverse himself or even apologize when required to do so by the President, who wrote “In future, I must strictly enjoin you to touch no man’s property without his consent, or the previous orders of the Commissioners“. A second incident of the same nature occurred when L’Enfant threatened to repeat his behavior–this time on property of the absolute wealthiest D.C. landowner, which Washington stopped only by alerting the Commissioner’s to L’Enfant’s intentions[99] Fergus M. Bordewich, the Making of the American Capital, pp. 86-7 .

Despite the reality that the Washington D.C. city-building project by the late fall of 1791 was “heading south” in more ways than originally contemplated, Washington painted a rather robust picture to Congress in the Third Annual Report:”And there is a prospect, favored by the rate of sales which have already taken place [all 34 of them], of ample funds for carrying on the necessary public buildings, there is every expectation of their due progress” [99] Elkins & McKitrick, p 175-direct quote, footnote 33. This from a man who never told a lie may be as close as he ever got to one. Washington, characteristically, persisted.

Footnotes

[1119] As we are reminded by Stanley Elkins & Eric McKitrick, the Age of Federalism: the Early American Republic 1788-1800 (Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 169: Jefferson had actual experience in the development of a new capital. In 1777, as Governor, Jefferson led/managed the relocation of Virginia’s capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, a village of 1,800. His responsibility which he directly assumed was to preside over the development of six large public squares “each with a handsome edifice of brick brilliantly porticoed”. The first public building to be specifically designed for a republican government was the classical capitol at Richmond. Based on the Roman Maison Carree at , and Nimes “and built from a design which Thomas Jefferson had prepared”. Also Jefferson had been an early player in the advocacy for establishing a port city on the Potomac–beginning in 1783. Despite his deep-seated discomfiture on the direction of the Washington administration apparently driven by Hamilton’s vision, Jefferson on passage of the Residency Act communicated to Washington his willingness and ideas on the matter (p. 170). He was Washington’s go-to man on the project–and whatever Jefferson’s vision on the politics and ideology of the national government, it included a federal capital at Washington D.C. Interestingly, Jefferson’s reading of the Residency Act took some liberties with the precise and limited language of the Act. I could argue he “implied” much in his reading–that the Commission could extend its development initiatives beyond the area and construction of specified public buildings, for example.

[1120] Washington, writing to Tobias Lear, observed Greenleaf (and the deal syndicate) had “dipped deeply into the concerns of the Federal City–I think he has done so on very advantegeous terms to himself, and I am pleased with it notwithstanding on public ground; as it may give some facility to the operation at that place, at the same time that it is embarking him and his friends in a measure which, although could not well fail under any circumstances that are likely to happen, may considerably be promoted by men of Spirit with large Capitals” Bordewich, the Marking of the American Capital, p. 158.

[iv] A new work, Colin C. Calloway, The Indian World of George Washington, Oxford University Press, 2018) literally opens up the topic of Washington as real estate speculator, city-builder, and ridden with conflicts of interest, President and formulator of Native American “foreign policy”–war and conquest. His 1791 St Clair Expedition into northwest Ohio was destroyed. The 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua between the United States and the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederation opened up Upstate New York for Holland Land Company settlement. The 1795 Treaty of Greenville, with the twelve tribes of the Western Confederacy failed miserably. But Calloway deals comprehensively with the multi-faceted Native American relations, with extensive information applicable to ED in the South as well as North.

[v] http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/winter13/washington.cfm[v] http://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/founders-land.html[v] http://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/founders-land.html

[vi] Robert Silsby, the Holland Land Company in Western New York. Volume VIII, Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society.

[vii] http://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/founders-land.html

https://www.google.com/search?q=cenus+population+1790+to+1990&oq=cenus+population+1790+to+1990&aqs=chrome..69i57.16685j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8file: Table 4: Population 1790-1990