Theme 2: MODULE 3

Hegemonic Industrial Big Cities:

BIRTH OF AMERICAN STATE AND LOCAL MED

This module touches on two broad topics: (1) the Early Republic rise diffusion of industrialization and urbanization that provided the foundation for the post-Civil War Big City hegemony; and (2) the development of agglomerations (19th century clusters if you will) in Gilded Age Big Cities. MED (Mainstream Economic Development) reacted to these dynamic drivers of economic growth and state and local ED was born. Said and done, it was the rise of industrialization, urbanization and the emergence of American-style capitalism that served as the midwife of MED.

Initially, the module starts out by explaining “Big Cities” and their industrial economic base which when combined with their post-Civil War dominance over the federal government established hegemonic control over the U.S. economy and de facto control over the other regions of America. Then we move onto how industrialization first developed in the Big Cities and briefly outline how it diffused across Early Republic America.

What is this “Hegemonic Big Cities” Thing?

The centrality of Big Cities in our history is because the large cities of the North and Midwest were the first to create a new American “industrial” capitalist economic system, an economic system that won the Civil War. The Civil War locked in northern control of the federal government–until the 20th century. With such power and economic centrality, these Big Cities, consciously and unconsciously, established a hegemony over the other regions and states. That hegemony lasted over one hundred years and was a central dominant factor in the history of American S&L ED until about 1975.

Northern/Midwestern Big Cities, the first on the industrial block, overshadowed to the point of colonializing the other regions–and the reaction of these regions to that Industrial Big City Hegemony and the length of time before they were meaningfully settled, created the dynamics which formed a distinctive southern and western economic development.

The impact of the Civil War, and the subsequent agglomeration of Big City economic bases is what really did the trick. The key was oligopoly and the rise of new sectors and industries. All of this was in effect fueled by the hordes of immigrants who entered the U.S. in the 1840’s and after. The hegemony was overwhelmingly the port of entry for the immigrants, and the Big Cities enjoyed a substantial advantage in acquiring a skilled, cheap and plentiful workforce–at a cost to be sure. In the next module we will discuss the specific MED strategies and EDO-types that dominated both Early Republic and Gilded Age.

Overview of 19th Century Mainstream Privatist ED (MED)

The Big “Big” Picture

Most observers are comfortable with that “thing” called the industrial revolution. Capitalism is another matter. In the United States the two pretty much overlapped. That meant American MED reacting to growth unleashed by industrialization and urbanization, also coexisted, reflected, and served as the link and often the agent of an emerging American-style “capitalism”, the economic system that produced the spectacular growth that transformed America to be the foremost industrial power in the world by the turn of the 20th century.

MED’s overlap with industrial capitalism meant Early Republic urban economic base were constantly being stirred up by industrial capitalism constant propensity to create new gazelle industries/sectors. The pot was constantly being stirred, disrupted in today’s parlance over each time period. Since the USA was in geographic expansion mode, moving deep into its wilderness interior, new market areas and population centers were forming each and every year. MED developed, unconsciously mostly, certainly unplanned, as each city and state confronted its own set of challenges and opportunities.

The initiatives, indeed the mere existence, of other urban economic bases threatened not only competition but potential economic obsolescence, while offering potential market areas in which to expand. The gradual development of an American national market into the Midwest, the Central States and Pacific West–and then after the Civil War into the South feed into the dynamic evolution of MED during the 19th century. This was how “imperialism”. the global capitalist movement of the 19th century, expressed itself in the United States. MED as it was practiced worked with the economic bases of the North/Midwest Big Cities–the headquarters of an increasingly oligopolistic industrial economy. Coming from a non-Marxist/socialist, doesn’t this sound Marxist! The specific strategies that characterized this dynamic growth will be discussed in the next module.

Capitalism’s offspring (businesses, firms, industries and sectors) constituted the nucleus from which MED goals, purposes, strategies and programs were focused. Nineteenth century limited government meant government took a backseat in these early years. Backseat drivers have a deserved reputation, however, and new urban policy systems emerged during and after the Civil War, and immigration entered into its steroid period that lasted until WWI. Big Cities became incredible growth machines during the Gilded Age, and MED was infused with another set of tasks, internal to the Big City: to manage and facilitate–to cope–with the physical expansion of Big City America. It did so in “partnership” with an entirely dysfunctional urban government. That is a story we will not tell until we get to Theme 3.

Let’s Be a Bit More Specific: Diffusion of Big City Industrialization and Urbanization

In 1790 we were an agricultural backwater, a former English colony dependent on coastline ports around which our economic system revolved. We traded and exported agricultural produce for our economic survival. In the minds of many today, the old agricultural economic system disappeared more early in our history than it actually did.

A little less than 4 million lived in 1790 USA; by 1860 about 31 ½ million called it home. Of cities with population exceeding 100,000 in 1860 all were port cities. Four were the original colonial ports (Boston, New York (including Brooklyn), Philadelphia and Baltimore), and four were inland port cities on Great Lakes and Ohio River (Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Chicago), and the Mississippi (New Orleans). New York City by then (1860)was already the boss. Its metro area totaled more than 1.1 million. It was the third largest city in the developed world, behind London and Paris—double the size of Berlin. Truth be told, post-1790 American ED was as much about people migration as the importation of the English industrial revolution.

The Revolutionary War/War of 1812 aside we were tied to the English economy and its empire which exported economic/religious refugees, as well as its accumulated traditions of city governance (including even the names of our cities). Our Early Republic S&L policy systems reflected these traditions, so did ED tools, and structures—that’s where the municipal corporation (as well as counties) originated. Chartered Corporations (both private and public) would become the first key American EDO—not the chamber (which was French anyway). But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

We looked to England for ideas, best practices, and for the latest, greatest technology to borrow, copy, or steal outright—and their investment capital most of all. As to the English industrial revolution, it was a pretty recent invention itself. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations was first published in 1776. By 1790, England had established a growing industrial base, but the manufacturing disease had spread across the English Channel to Paris, and that was not good: London and Paris were at war—and would be so until 1815. On the whole, American MED benefited from the English industrial revolution—its industrialists/finance capital provided finished goods, technology, machines, skilled laborers/entrepreneurs, seed capital, and even foreign direct investment. Our early Silicon Valleys were Manchester and Liverpool and our first neo-Liberals were English finance industrial capitalists.

American cities started this period as very small, late-medieval commercial centers, without elementary capitalist institutions such as commercial/savings banks, home resident manufacturers of little scale and technology. Grossly dependent on their geographically restricted hinterland, relying as it did on medieval modes of transportation, each city was an island unto itself, surrounded by a wilderness. In 1790 about 220,000 Americans (out of nearly 4 million) lived in its ten largest cities—the smallest of which was about 5,661 residents.

Early Republic growth, while impressive, probably is less than most of us imagine today. The 1860 census reported 400 urban centers with population greater than 2,500—with one fifth of the American population (over six million). It was one-twentieth (5%) in 1790. Say it another way: 19 out of 20 Americans lived in rural areas in 1790. My home town, Salem Massachusetts, was the nation’s seventh largest city; next door Marblehead was the tenth. It was not until 1920, that a bare majority of Americans lived in urban areas.

The first American factory (Slater’s Pawtucket textile mill) got its rough start, and Washington’s First State of the Union was given in the same year: 1790.

The earliest Big City sector gazelle was textiles. Samuel Slater, newly arrived in 1790 Pawtucket RI (a vibrant metro powerhouse that did not become a city until 1828 or be reported by the Census until 1830 when it had accumulated 1400+ citizens), constructed America’s first textile mill, powered by river water currents, around 1791-3, in what is now Pawtucket’s downtown.

A generation later, infused with Boston investment capital, the Boston Manufacturing Company innovated a revolutionary factory-based industrial process, purchased cutting-edge British machinery, lodged in huge (for the times) mills, and worked by a recruited young female population housed in nearby dormitories. From its 1813 factory, American industrialization supposedly sprang. That’s what the textbooks teach anyway.

Industrial innovation and sector diffusion was more complex than that. Lowell’s and New England textile spinning took advantage of New England’s entrepreneurial Puritan elite which by that time had accumulated its own finance capital, and which sanctified the role model of the hard-working and creative business entrepreneur as a legitimate occupation for its wealthy elite. New England finance capital using its own funds built railroads, adjusted to technology change in energy-power, and relied on coastal and sea transport literally owned by the guy living next door on Beacon Hill. That model of industrialization was carried to New York City when Boston investors relocated there around 1800, but it does not reflect how industrialization usually diffused to other Big Cities.

Innovation and manufacturing diffusion required sufficient local capital, and willing local wealthy elites—and it had no easy access to non-hinterland markets. Rather than a dramatic introduction of a brand new high tech factory and importation of a new labor supply as typified in New England, the alternative path to manufacturing evolved much more gradually—and organically—from craftsmen and artisans.Watching afar, they copied what technology and processes they could, invested their own sweat equity, fabricated their own innovative technology, and operated on a small scale across an incredible variety of products, ranging from shoes, jewelry, chemicals to machine tools, starting a new sector, even industries from virtual scratch.

Early innovation led to head starts for the fortunate firms, the copycat entrepreneur next door building down the street. They shared the workforce, each devised and than had stolen its technology. If you survived that attracted investment. Timing was everything, as Panics discouraged investment. All this combined led to individual cities developing their own mix of sectors, industries, firms, and banks. It also fostered “agglomerations”[ii]—a local economic base whose manufacturing was disproportionately dominated by a sector or two, or three.

An example of all this is a working artisan, Linus Yale Jr. Yale’s Dad, about 1840, patented a lock technology devised some manufacturing processes, and incorporated his own business in Newport NY, in effect creating an American sector, locksmithing. He then experimented and then adapted all that to a mass-production. His son patented improvements and processes a decade later and by 1868 his firm employed a whopping 39 workers. Between 1849 and 1871 he filed twenty patents. Look below and see the 1897 manufacturing facility he built. Betcha somewhere on your keychain is a Yale key. The more common form or model of Early Republic manufacturing innovation was Yale’s.

Small business at its core, it relied on entrepreneurial innovation, hard-work, and a creativity that persevered through decades. “Industrialization was not alien to, but often emanated from, the preindustrial American artisan class, and the inventiveness, entrepreneurship and capital of small producers was a vital force in early nineteenth-century industrialization”.[iii] Fortunately, Google or Allergen wasn’t around to buy them out. I’m not sure if Peter Thiel’s investment model could relate to Yale key. In any case, small business becoming big business is not a 21st century innovation pertinent only to technology firms.

Anyhow, Yale’s organic model does much to explain 1860 Newark NJ.

Newark was the nation’s eleventh largest city in 1860 with a population of 71941, and the values of its manufactures, $28 million, was the sixth largest in the country. The output of six crafts—shoemaking, hatting, saddle making, jewel making, trunk making, and leather making—accounted for 42% of that value. All six crafts had been practiced in Newark in their traditional form, and artisans had guided their evolution into major industries by 1860. … [Indeed] By 1826, over 80% of Newark’s labor force was engaged in some form of manufacturing: thirty-four distinct crafts were practiced in the town. … Relatively few men worked at each craft except shoe making, and most men labored alone or in small shops, the average workshop contained only 8 men.[iv]

Knowledge-based ED came instinctually to these Newark artisans. They set up an Apprentice Library in 1828, open in the evening. Also, in 1828 114 Newark craftsmen founded the Newark Mechanics Association for Mutual Improvement in the Arts and Sciences. It held regular meetings and provided workshops and speakers. This type of entity was not uncommon. The best known in the Early Republic was Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute-which, BTW, is today’s Franklin Institute and Science museum.

There are literally thousands of such stories. They speak to a capitalism that apparently has since been lost, not appreciated, or judged archaic and corrupted with inequities. It is, however, the capitalism that Big City MED witnessed through most of the Early Republic years—its formative years.

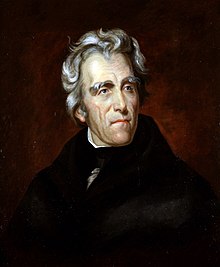

Accordingly, there wasn’t anything remotely resembling industrial capitalism previous to Andrew Jackson in the 1830’s. Jackson’s rise is directly tied politically to the rising industrial economy, and the disruption and change it created. Immigration, BTW, took off only after Jackson was dead.

His was a “nativist” populism–but it intruded into Big Cities politics. Urban political machines would later follow. Jackson’s impact on MED was considerable. His weak mayor system was adopted by nearly every major American city, his termination of Clay’s American System took the federal government out of state and local economic development–and his legacy, the Panic of 1937 scarred and made more difficult the future evolution of MED. His tariffs protected, however, the emerging manufacturing sectors and industries–at the expense of southern export of cotton–but that was compensated by his seizure of Indian lands, lands that later became the Cotton Belt.

So people migration and gradual industrial economic growth fueled Early Republic northern MED. After 1840, for the next seventy years, pure explosive population, and innovation-saturated economic growth were the ingredients with which MED economic developers had to work. They created none of these ingredients; rather they lived off them and maximized their impacts, both good and bad. That story will be told in the next module.

The Impact of the Civil War on MED

Using Davis’s index of industrial production, the 1790 index was 4[i]. By 1810, the index finally broke single digits, exceeding 10, It was not until 1826 that it doubled to 20—it was actually a bit lower than 20 in 1829. It reached 40 in 1836—and held on through the early Panic years. The index took off in 1843 (53) and by 1850 broke 100. By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, it reached 158; at the end of the Civil War (1866) it was 193. At the beginning of the Gilded Age (1870) the index was 243—by its end, thirty years later, it had grown to 1,182 (and by 1915 to 1,954). The index measures national industrial production, and hence does not reflect the destruction of southern manufacturing resulting from burned out cities. This index mostly measures the growth of Big City industrial production.

Among the important lessons learned from this index is that American industrial growth was remarkably steady before 1860 although given to spasms caused by Panics and Civil War. Spectacular growth was mostly a post-1870 Gilded Age explosion.

It was the Civil War that led to the “break out” of American industrialization. Through the Early Republic years, industrialization was found in Big Cities–and smaller independent cities. It had even oozed into southern cities. But the war changed all that. Howells’ Silas Lapham observed upon returning to Boston from Civil War military service:

“I found that I had got back to another world. The day of small things was past, and I don’t suppose it will ever come again in this country” (p. 26).

What does not show up in the Index is that American industrialism was extraordinarily uneven geographically. Until the 1890’s the other regions benefited little from industrialization and manufacturing employment. Until 1920, there was little challenge to Big City manufacturing— a Big City industrial, manufacturing economic hegemony indeed existed.

Big City MED reflected a seemingly inevitable growth, a surplus of investment capital, a constant supply of cheap but quality labor, and the ability to expand national markets and reach beyond local metro hinterlands. MED concentrated on cheapening the factors of production, fostering labor conformity, and protecting one’s jurisdictional economic base from erosion to other growing regions, states and cities. Oligopoly, mergers, macroeconomic disruptions, and providing a livable, accessible urban experience for its management and labor were its chief tasks—that and repelling political/regulatory intrusions from governments and labor.

In a later module the reader will be able to compare the northern Big City context with those faced by southern economic developers, who either resisted industrialization (preferring agricultural export) or stole it, Willy Sutton-like from those who possessed it. Lacking the heritage of having started a Civil War or permitting slavery, western jurisdictions chose another path and instead figured out how to intrude into Big City business decision-making to attract investment and jobs–we call it boosterism today. They exploited their growing population and the potential of their increasing markets. Both the West and South relied on city-building and transportation infrastructure.

Agglomeration: Forming the Hegemonic Economic Base

After 1800 the American economy slowly shifted from agriculture to an industrial economy. Every Big City developed some level of manufacturing during the Early Republic, and manufacturing firms were highly-prized targets of state and local ED. Early tax abatement, however, were seldom used to “attract firms”, but rather to promote startups, and retain existing firms with potential to exit in favor of entering new market areas. From the get-go, however, each city developed distinctive sector/industry combinations of sectors and industries and its distinctive policy system and MED paradigm.

Most Big Cities also developed an agglomeration, a disproportionate number of firms in a single industry sectors. Agglomerations in these years were young, and vibrant—centers of employment around a nexus of suppliers. The early industrial powerhouses were transportation-related sectors. Railroads provided markets for steel, coal, iron and numerous metal-bending, machine-making firms. Railroads required capital and financing—and that spurred everything from banks to local stock markets. Shipping across markets spawned insurance and logistics firms (warehousing, stockyards, and grain silos). The downside was two-fold: oligopoly in the industry created winner and loser cities, and railroad consolidation had serious effects upon jurisdictional economic bases.

In the meantime, however, railroads–the only inland transportation mode that could operate on a continental scale–was not only the best, but the only way to access and link to the national economy. By the Gilded Age, if not much earlier, cities had lost their ability to be an “island unto itself”.

The Civil War set agglomeration growth in motion. Huge profits, inflated prices and government contracts spread disproportionately to some sectors. With the closing of the Mississippi to the Northern farm produce, Midwestern agricultural exports moved along new routes. Chicago, and Buffalo, benefited enormously. Farm implements were in great demand. Pittsburgh, Troy and Philadelphia developed metal work specialties for cannon, rifles, locomotives, and metal to convert wooden ships to ironclads. Philadelphia erected 180 new factories in three years—becoming in the process the nation’s leader in manufacturing. With cotton unavailable, New England textiles switched to wool (uniforms and blankets), and the newly-invented sewing machine prompted shoe factories to spring up in New England textile centers.

Safe location near key resources spurred army and war products production by existing firms while inviting competitors to locate nearby. New Haven attracted six firearms/locks factories. Pittsburgh benefited from new iron and steel foundries for war-related goods. The federally-owned Springfield (MA) armory and its St. Louis drug laboratory both attracted smaller firms to open (McKelvey, 1963, pp. 21-2).

The Gilded Age dispersal/agglomeration of manufacturing sectors was often serendipitous—an innovating entrepreneur launched the startup in a particular city simply because that is where he lived–and the sector developed initially in that city. Rochester, New York provided an excellent example.

The Erie Canal triggered a major flour processing sector in Rochester, whose workers in turn supported clothing, shoe, brewing and woodworking facilities. Its population grew to 100,000 by 1885. In 1880 a largely self-taught local 26 year old Rochester Savings Bank bookkeeper with a bright idea, George Eastman, quit his day job and opened up the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company.

In 1885 the former bank teller got his first patent for a roll-holder device (so cameras could be smaller and cheaper); he sold his first camera, the Kodak, in 1888. Eastman pioneered advertising slogans—his being “you click the button, we do the rest”. By 1927, Eastman-Kodak was the largest firm in that industry sector and in Rochester–in 1960, Eastman-Kodak employed 60,000 Rochester area residents. In 2017, it is the area’s 16th, employing about 1700–there’s a lesson, or two, in there somewhere. In any case, Gilded Age MED included agglomeration management.

Manufacturing oligarchies started in the 1890’s. “The typewriter brought life to Ilion, New York, and new vigor to Syracuse; telephone factories clustered for a time at Boston and Chicago, but soon spread out; the cash register placed Dayton on the industrial map. … Bicycle companies sprang up in a host of towns … but shortly after 1899 when the American Bicycle Company absorbed forty-eight of them; production was centered in ten plants at Springfield Illinois and Hartford, Connecticut” (McKelvey, 1963, p. 42). Agglomeration, usually smaller, spread from Big Cities to second and third tier cities.

Drawing on local technology, nearby resources, or the production of an agricultural hinterland, many smaller cities specialized in certain kinds of manufacturing—rubber in Akron, glass in Toledo, cash registers in Dayton, electrical products in Schenectady, fur hats in Danbury, brassware in Waterbury, silverware and jewelry in Providence, collars and cuffs in Troy, leather gloves in Gloversville, brewing in Milwaukee, flour milling in Minneapolis, farm machinery in Racine, meat packing in Kansas City and Omaha, cotton goods in Fall River and New Bedford, shoes in Lynn, Haverhill and Brockton, steel in Youngstown, Johnstown, Birmingham and Gary. Many of these cities also became regional marketing and financial centers, for industrial activity of any kind generally stimulated subsidiary industries (Mohl, 1985, p. 60)

Industrialization and urbanization followed distinctive paths, in each of our Big and small northern/Midwest cities. While most cities developed dominant manufacturing sectors, others, however, clustered around finance or hinterland assets. Finance sectors constituted New York City’s core; it developed into the nation’s financial capital. Des Moines, Iowa (Equitable Life Insurance Company) and Hartford developed into America’s insurance capitals. By 1880 there were 6500 plus banks with national, state or private charters. Several cities became regional banking-finance centers after the passage of the National Banking Act of 1864. Regional banking centers, however, were dependent on the investment and money capital banks headquartered in New York City.

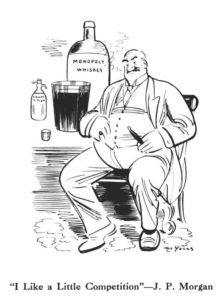

Both finance, and transportation manifested an early and pronounced tendency to form an oligarchy—compatible with metropolitan decentralization of branch offices, but which centralized economic power and leadership in a very few headquarters cities.

Another pattern affected cities whose economic base developed around natural resources/extraction and processing. Eastern coal-mining cities of Hazleton, Scranton and Wilkes-Barre Pennsylvania and coal/oil/gas towns surrounding Pittsburgh/ Toledo are examples. Absentee ownership, innovation in logistics, technological change, and unstable pricing of their product were key factors affecting these natural-resource-based jurisdictions. They will all be mentioned in later modules, but the Gilded Age was their golden years.

In the 19th Century, Big City MED was mostly internally-focused, involved in urban governance, infrastructure, and coping with the dynamic physical growth and geographic specialization of the expanding Big City. The Big City’s principal competitors were its nearby neighbor Big City’s industrial firms and Big Cities elsewhere rising from seemingly nothing–new markets that offered opportunity not threat. Each city’s economic base developed its own economic personality, composed of sectors which would experience different time clocks in their profit life cycle.

Entrepreneur, Innovator and Investor, sector by sector, city by city, time period by time period our cities and their economic bases grew their own particular and special economic “garden” of firms, sectors and industries—and workforces. Like fingerprints, no municipal economic base was a mere clone of its neighbors, or far-away states.

A Few Takeaways

In 1790 or even as late as 1820, the American city and economy is not modern. The story of how they became modern is the story of 19th Big Cities. That sustained growth provided the background context for the development of Big City MED. Big City MED by the beginning of the 20th Century reflected its experiences, conditions, sequence of growth, reaction to and the accommodation of dynamics, inefficiencies, and legacies encountered by 19th Century Big Cities. Late-blossoming western/Midwestern Big Cities faced a world remarkably different than their earlier Eastern compatriots. The later one got on the industrial roller-coaster, the more its MED departed from that of its older urban brothers and sisters.

FOOTNOTES