Theme 2 Module 4

Early Republic CD: Brahmin Elect, Josiah Quincy

First CD Wing—The Elect–Foundation Wing

As Two Ships devotes considerable space to the development of “The Elect”, starting with its founder, Puritan Governor of Massachusetts (the first, BTW) John Winthrop, and outlining its evolution to the start of the American Revolution. I used this valuable space because I believe “the Elect” is one of the most powerful forces in our S&L ED history. As we shall see the Elect occupy a hazy area between MED and CD, between Privatism and Progressivism. How they came to occupy such ground and why they are so important to our history is discussed in Theme 1, Module 4–which I strongly urge any reader to read if they have not yet done so. This module builds upon “Wings of CD”.

Updating the Evolution of “the Elect”: First Wing of Community Development

The 1790 American Republic was pre-industrial and pre-urban. Former English, German and Scotch-Irish immigrants—and Black slaves—demographically dominated. The years that followed witnessed relatively low immigration rates. After nearly 200 years of settlement, the East Coast had developed its own produced its own native elite based on wealth/social status.

Inspired by religion, the different religions (which BTW settled in different states), evolved in different ways. Of to the side were Tidewater slave-owning plantation elites, whose wealth, power, and economy rested on the scarred backs of Black slaves. This Tidewater southern Elect, leaders of the American Revolution, and anti-federalist to the core, drifted off to form the Jefferson-Madison Democratic mass-based political party. Quakers, on the other hand, despised government and Quaker elites withdrew from politics, secluded themselves on their estates, leaving the political leadership “space” to Privatist small businessmen. They formed the nucleus for Sam Bass Warner’s “privatist city”. In Boston, however, the formerly Puritan-Congregational-Unitarian New England business elites jelled into the New England-style Brahmin” “Elect”—the 1790 successors to John Winthrop, and driving force behind the Federalist Party

Not content to stay in New England or to spread into New York and the Midwest through a Yankee Diaspora, they also infested New York City. New York City’s post-1790 explosive economic and population growth drew throngs of aspiring New England businessmen to Manhattan. In 1790 the city director listed 248 merchants; by 1800 there were 1100-a four-fold increase. A large body of newcomers came down from New England, bringing new expertise, capital, and connections … [and sufficient] to warrant formation in 1805 of “the New England Society in the City of New York”[i]. The New England Brahmin had carved an influential foothold into the New York City policy system. This will prove important in the formation of CD’s Second Wing.

Accordingly, this module’s Elect discussion begins with “the Boston Brahmin Elect” in the Early Republic years, focusing on describing how (1) it survived following the collapse of the Federalist Party–and its ouster from national politics–and (2) its entry into 19th century S&L policy systems and ED policy-making. To do this we examine Boston’s “Great Mayor” Josiah Quincy III, a Boston, Andover-Harvard Brahmin, relative of Abigail Adams, former Federalist Congressman, member of the Federalist Party’s Central Committee–and after his ouster from the Mayoralty (1829), a sixteen year President of Harvard.

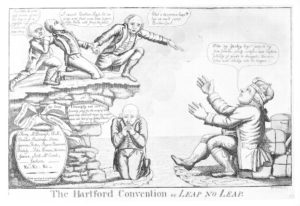

During the first two decades (or so) of the Early Republic, New England Progressives took over the new Republic in the national capitol. Textbooks focus on Washington and Hamilton, perhaps John Adams and their “Federalist” Party. The nation’s capital was where the action was, so the Boston Brahmin Elect went to Washington. That changed in 1800 with Jefferson’s election. Federalist fortunes collapsed during the War of 1812, the secessionist New England Hartford Convention, and the rising tide of Democratic-led “Era of Good Feeling”. That proved the death knell for the Federalists. By the 1820’s Massachusetts Federalists had long since moved back from whence they came, their moving vans, heading back to Boston.

Josiah Quincy III: Role Model for Future Elect Municipal Leaders

Quincy is chosen for many reasons. His is not the only example of ‘the Elect” in that time period, but he is the best. Why? Mostly because the Puritan/Brahmin-Elect “style” proved to be especially impactful in the our history–key players, for instance, in the founding of our Second CD Wing (see next module). Quincy also allows us to clearly recognize the class dynamic within both First and Second wings. That the wealthy classes sought to help, some called it reform, the middle and lower classes created a tension with the Third “mobilization” Wing, but, on the other hand, a compatibility with the Fourth and Fifth Wings–all of which seriously impacted the subsequent evolution of American Community Development. Finally, Quincy’s CD/MED agenda, which he is the author, provides the first example of the Elect’s hybrid ED governance agenda–and being the first, his example is worth noting given its early, 1823-9, application.

We can see in Quincy, even in these early years, key enduring Brahmin Elect characteristics such as sympathy to emerging industrial capitalism, an overlap with MED strategies, but critically, a willingness to use government as a vehicle for social and political empowerment for the common people, and for the community or public good. In the last characteristic Quincy crossed the line, entering into Progressive territory–in the same spirit as Winthrop had two centuries before.

It might also be mentioned that the Puritan/Brahmin-style Elect seemingly possessed a “default” preference for national government, a preference which shall be further supported by Theme 3’s description of the19th century Chamber of Commerce and its 20th and 21st Century behavior. With each extension of industrial capitalism into national, continental and now global markets, the Puritan/Brahmin-style Elect has shifted its policy focus to participate in the “commanding heights” of the prevailing economy , diminishing its commitment and involvement in “lower” levels of government and economy. Diminished though it may have been, the rise of foundations and philanthropy has proven a viable substitute for personal involvement of the Puritan/Brahmin-Elect.

We can see this in Quincy’s previous career. After one two-year term in the Massachusetts Senate, Quincy headed off to the House of Representatives in Washington (1805). There he stayed until 1813, when he left Washington in frustration over the Jeffersonian Democratic realignment and the entry into the War of 1812. The Federalist Party collapsed nationally, in considerable measure due to its “elitism” and its near succession during the infamous Hartford Convention. Quincy effectively, was kicked out of national politics–and in frustration he returned home. He served in the Massachusetts Senate until 1820. When he retired from the Senate in 1820, he was subsequently elected Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (1821-22). That is when we begin our tale.

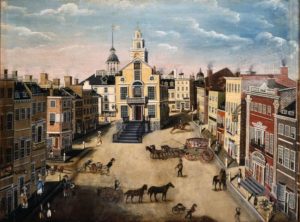

Precondition for Quincy’s Mayoralty: Change in the Municipal Policy System

In case you didn’t notice, by the time of Quincy’s arrival on the Boston scene, we are thirty years into the Early Republic. Industrial capitalism is clearly emerging in the Big Cities. Boston in 1790 had been a thriving cosmopolitan finance-trading seaport town of 18,000 (America’s third largest municipality). By 1820, Boston increased to 43,000. Immigrant waves were still pretty much in the future. As far as Boston and Massachusetts politics was concerned, the Federalist Party is still dominant. Boston is still a Town, not a City. The State of Massachusetts is the dominant player in S&L ED and general policy-making.

Boston politics described, by historian Ronald Formisano, as “deferential-participant politics” in which non-elite voters “followed the lead of their cultural and economic betters–voting often against their best interests”. That, however, was clearly changing, as new classes were developing (manufacturing artisans, local service sector, business owners and workers) whose interests were not only not served by the Federalists, but were consistently short-changed. Primarily nativist Protestants, economic change (Corn Laws) in the British Isles had laced Boston with its first Irish Catholic rural immigrants–Thomas O’Connor estimated that by 1825 there were 5,000 of such in Boston. They, were Boston’s undeserving poor, desperately unskilled and unemployed.

After two generations in power, the Federalist Party itself had centralized its decision-making into a Central Committee, functionally similar to the ethnic political machines that would follow a few decades later. In 1820, Quincy was a member in reasonable standing in the Central Committee. There was a Jeffersonian Democrat Party in Boston, and especially in the Massachusetts hinterland today, which today we call Maine. Maine, in 1820, was allowed to split off and become a state. This left the Town of Boston (and neighboring Essex County) as “the” major Federalist “stronghold”–destined not to last long–thanks in considerable measure to Quincy.

Quincy, always a maverick, a bit of a curmudgeon who spoke/voted his mind, usually controversial, and often wrong. He was ambitious, and restless. By 1820 he had had it with the conservative, self-serving, closed nature of the Federalist Central Committee and for opportunistic and policy reasons resigned the House Speakership and eventually the Speaker of the House and instead accepted a judgeship from which he rendered decisions favoring the Boston middle and working classes. By 1822 he was at war with the Central Committee. He was not alone–that is the point–the Federalist Party was breaking up locally.

A national panic hurt the Boston economy severely. The Democratic Party, weakened by loss of Maine, joined a coalition led by “populists”(organized into “the Middling Interest” social/political reform group), the Boston newspaper, and a rising business class and tradesmen–expressions of Boston’s emerging industrial revolution, often hinterland entrepreneurial migrants–to oust the Federalists. Guess who was a leading member of that coalition. The political revolt achieved critical mass around 1820-21. First centered on a state constitutional convention, from which came one success: approval of Boston’s city charter. Boston accordingly proceeded to set up a new municipal weak mayor policy system, and elect its first mayor (with a one-year term). Boston’s municipal government, limited in its powers, still remained dependent upon the Federalist-controlled Massachusetts state legislature.

The Federalists fought back. In a mayoral close election, which Quincy lost in the last few days. A close friend, recruited to divert votes from him, was elected as Boston’s first mayor. The friend, however, was sick, inept, with a “tin ear” to the shifting currents would die shortly after his term was over. Quincy ran again in the next mayoral election (1822) and was elected by coalition voters . He ran six more times before he too was ousted by yet another coalition (1829).

In between those years, Quincy pioneered a model for “the Elect” to serve as a “charismatic” mayor successful in mass democratic politics, who bimodally (1) advanced the interests of the Boston economy and business, while (2) devoting considerable attention to the improvement of lower classes, and the overall community “good”. In so doing, he led several efforts to strengthen the capacity of city government, establish a greater autonomy from state involvement, and create, for the time, a strong mayor form of government (a new policy system)–not typical of that time period. His economic/ community development initiatives were cornerstone elements in his larger policy agenda. The centerpiece of his ED strategy was America’s first urban renewal initiative.

The “Elect” Takeover Boston

Elected in 1823 as Boston’s second mayor, Brahmin Josiah Quincy faced several built-up pressures and delayed reforms. In a general sense Boston’s infrastructure and service sectors were in crisis. Federalists in the state legislature, weakened to be sure, remained a barrier to local efforts. The shift from town to city was no panacea for Boston’s problems. The office Quincy inherited had no veto power, he had little influence over the municipal budget–controlled by a bicameral (House (forty-eight representatives from twelve wards) and Senate (eight members) city legislature, few meaningful appointment powers–and a one year term.

Policy, such as it was, was made chiefly by five independent “boards”, inherited from town government, and elected, thus independent from both the legislature and mayor. The boards held effective monopoly over the critical policy areas of urban governance: Health, Highways–Roads, School system, Overseers of the Poor, and Firewards–the ill-organized coordinator of the city’s competing volunteer fire departments which were more social clubs and organized thugs. There was no police department, and from our perspective no department of ED. This was a commission form of government on steroids. Both mayor and legislature were dependent on these boards for program implementation electorally, and for effective governance. The mayor was a symbolic leader–but that was not Quincy’s style or temperament.

The initial crisis was “garbage” on the streets. A nice word “garbage”, its actual content was less so–smelly, grossly unhealthy–and a very high accumulation. Locals in speaking before the Board of Health described it as “filthy, putrid and nauseous”. The Board acting “responsibly” agreed and demanded the mayor and legislature clean it up. They, of course, had no responsibility for such action. The first mayor did nothing, and so the accumulation was that much deeper when Quincy took over. By that time, the simple public health aspect of garbage pick up acquired yet another CD meaning.

The garbage had gotten so deep, the “trucksmen” could no longer ply their trade. They could not get their carts into many streets. Who in God’s name were the trucksmen, and why should we care? They were poor Bostonians of all persuasions who transported goods from Boston’s docks to the city–and hinterland–retailers. Somehow, amazing to believe, not all of the goods made it to the retailer. Trucksmen would then to to poor neighborhoods and streets and sell these ill-acquired goods at a considerable discount to Boston’s poor. The trucksmen mobilized–and Quincy would take their side.

The second issue was Boston’s debtor prisons. The reform du jour, advocated by the Middling Interest, was that inmates should be allowed to work during the day and return at night. Debts could be repaid and inmates released, and their families better served. This problem fell under the jurisdiction of the Overseers of the Poor–who commanded a very large budget indeed. They had instituted a practice of “contracting” inmates for jobs, the payment of which went to the Board–this was a part of Boston’s manufacturing proletariat. A slug fest between the legislature, led by the Middling Interest, and the Overseers followed. Because the Middling Interest drew its strength from wards, the termination of wards as electoral districts entered the debate–and became the prime issue. Class warfare resulted. The Bostonian and Mechanics Journal pushed back:

The old doctrine of passive obedience and nonresistance (by the working classes–poor) has long since exploded … the monied few (traditional Federalist/Brahmin Elect) are yet to learn that wealth alone will not entitle them to honors or distinction in this republican government. The industrious mechanics and virtuous tradesmen are entitled to equal privileges … not withstanding the growlings and complaints of a paltry, self-created nobility … We are not of that servile race who bow in adoration to the proud aristocrat because he has money” (Mathew Crocker, the Magic of the Many: Josiah Quincy and Rise of Mass Politics in Boston, University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), p. 105)

When Quincy became mayor, he sided with Middling Interest and “the Bostonian”. Class warfare, arising from industrial capitalism, fragmented what had been a monolithic Brahmin Elect. Quincy, from our perspective had wandered into community development and social-political transformation. He had taken the side of Middling Interest, an early Third Wing CD movement (see next module).

Adding fuel to the fire, the first mayor, following Federalist demands, started revoking liquor licenses from long-standing neighborhood bars–particularly Irish bars. Shades of immigrant discrimination and Prohibition had appeared (both of which would haunt urban politics for the next one hundred years). Middling Interest took the Irish’s side. Quincy in his second run at mayor did also.

Let’s take a step back and consider how Quincy altered what was the dominant Brahmin Elect policy agenda, and inserted a new (actually Puritan) tenor, a CD tenor, into the Brahmin Elect. Crocker summarizes this transformation:

Josiah Quincy would govern Boston in a different way than Boston’s past leadership. He did not expect the “people” to be bound to his “service” per se; instead, they would be bound to the corporate good of Boston as he (Quincy) saw it. Unlike the dominant political order before the Middling Interest movement, the people’s support, and even the people’s deference to Quincy and his administration would be earned through active municipal policy and not expected because of his status in society …. Quincy would court the collective interests of the majority in Boston. (Crocker, p. 116)

Single-handedly, Quincy had forged a new conception of Brahmin-Elect Progressivism, capable of successfully functioning in the new mass politics of the Early Republic urban democracy. In so doing he began a tradition that only grew in strength over the next century, with his grandson, and then his Progressive Era great-grandson, both of which served as effective CD-Elect mayors of Boston. With great irony, the latter turned over his mayoral office to the first Irish machine mayor, JFK’s grandfather, “Honey Fitz”.

Quincy would be also adapted to a new turn of the century style of Big City mayors, the social reform mayors, the last of which was New York City’s beloved LaGuardia. In Quincy, the reader sees the first of the Classical Era’s prototypical Progressive Elect mayor. By La Guardia’s time one didn’t need to be rich and “Elect” to be a CD Elect mayor–it had become a “state of mind”, an approach to urban governance which drew up old Puritan values, beliefs and priority to serve the common good and the needs of the disadvantaged–despite the dictates and theories of capitalism. The irony of all this, the irony that has often bedeviled the Brahmin Elect mayor, was that the poor and Irish did not vote for him. He won by only 325 votes, mostly votes from the Middling Interest, a middle-class movement of artisans an aspiring middle class–and disgruntled Federalists.

Quincy’s Hybrid MED/CD Economic Development Agenda

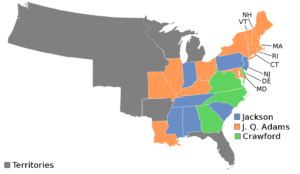

A close examination of Quincy’s six-term hybrid ED agenda offers an additional insight to our history: Quincy’s linking of the ED agenda to the reconfiguration of Boston’s policy system from an exceptionally weak mayor to a moderately strong mayor form of government. This shift was counter to the tenor of the times, thoroughly Jacksonian (the highest vote-getter in the 1824 presidential election), which weakened the executive power in most Big Cities and cities/counties across the nation.

Quincy’s strategy, promulgated in his initial 1823 Inaugural Address, was to directly attack the dispersion of executive power lodged in the five independent boards. He did this by adopting the Middling Interest and lower class demands and using them as his policy wedge to bring the boards to heel–indeed to end them outright, and establish mayoral departments. At the outset he attacked Health, Overseers of the Poor, and Streets. The last fell quickly and easily. Quincy appointed his own Superintendent of Streets , and then authorized him to hire teams of sweepers to remove seven thousand tons of “filth” from city’s streets, which he then sold as fertilizer Acquiring control over the city’s sewers, he subsequently minimized harbor and street pollution. Presumably, this made the truckmen very happy.

Quincy’s rationale for moving on the filth overlapped with his attack on the Board of Health. Decrying the adverse health effects of the filth on the city’s poor as justification of his attack on both bureaucracies, Quincy asserted in his Inaugural Address that “To those whose fortunes are restricted, these powers [over the bureaucracies which he demanded] ought to be peculiarly precious. The rich can fly from the general pestilence … in the hot summer months due to the inept Board of Health. In the seasons of danger the sons of fortune can seek refuge in purer atmospheres. But necessity condemns the poor to remain and inhale the noxious effluvia” (Crocker, p. 134).

Without specific authorization, he empowered the city marshall to acquire a fleet of carts and horses, hire laborers and remove health hazards and establish municipal garbage pickup. He then summarily dismissed the Board of Health, who apparently emptied their desks and went home. An 1824 referendum ended the existence of both boards. In that year he went after the Overseers of the Poor, accusing it of corruption. He lost the referendum calling for its elimination, and responded by simply selling the Overseers assets such as the infamous debtors jail. Inmates had to be moved to a facility the mayor controlled (South Boston House of Industry). The State, however, continued its support for the Overseers of the Poor, but Quincy had addressed the Middling Interest’s demand for debtor reform.

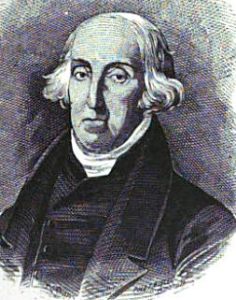

Thomas Melvill, Grandfather of Herman Melville, who Quincy Replaced as Firewalls Commissioner in 1825

The Firewards Board, however, was serious and long-standing player in city politics. Composed of sixteen autonomous and competing volunteer fire fraternities who fought each other on the way to a fire and after. Membership in these fraternities was passed from father to son, and in between fires the fraternity acted like a neighborhood social club. Quincy, however, advocated “professionalization” and their conversion into a municipal department with up-to-date equipment and training. Predictably, his proposal went nowhere–until in 1825 a large section of the Boston CBD burned down and the fire fraternities were generally perceived as making a bad fire worse.

Quincy immediately pushed a new referendum abolishing the system–and it passed. Quincy immediately converted it to a fire department with his own appointee in charge. Reaction was intense, but Quincy hired a goodly number of the fraternity members, a total of 1,200–a very large number in a city of 40,000–and bought twenty new engines, a hook-and-ladder company, 7,000 feet of hose, 25 horse carriages, and tossed in 800 buckets just in case. Quincy not only created and modernized his fire department, but acquired a patronage fiefdom in the process (Crocker, pp. 137-8).

Creating the nation’s first municipal fire department and debtors reform are not usually thought of as CD strategies today, but they were the chief issues pressed by Middling Interest–and certainly the removal of filth from neighborhood streets and a garbage pick were. He followed up by creating the nation’s first police department (hiring a great number of truckmen), and a department of corrections for youth offenders.

In the pursuit of his CD agenda, Quincy “established a municipal bureaucracy of experts accountable to him. Quincy then appointed himself as chairman ex-officio of the considerable number of independent boards and commissions and assumed authority not contemplated by the state constitution or the shift to city status” (O’Connor, 2002, p. 93). Ahead of his time, Quincy made Boston city government a true service delivery provider–with all that entails. It cost a fortune, and not a small one either. This would haunt him the near-future. What put him over the top,fiscally, however, was his MED agenda: CBD and waterfront modernization/upgrade.

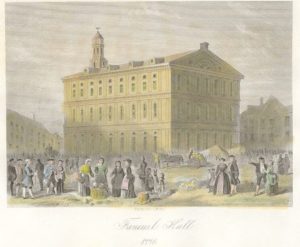

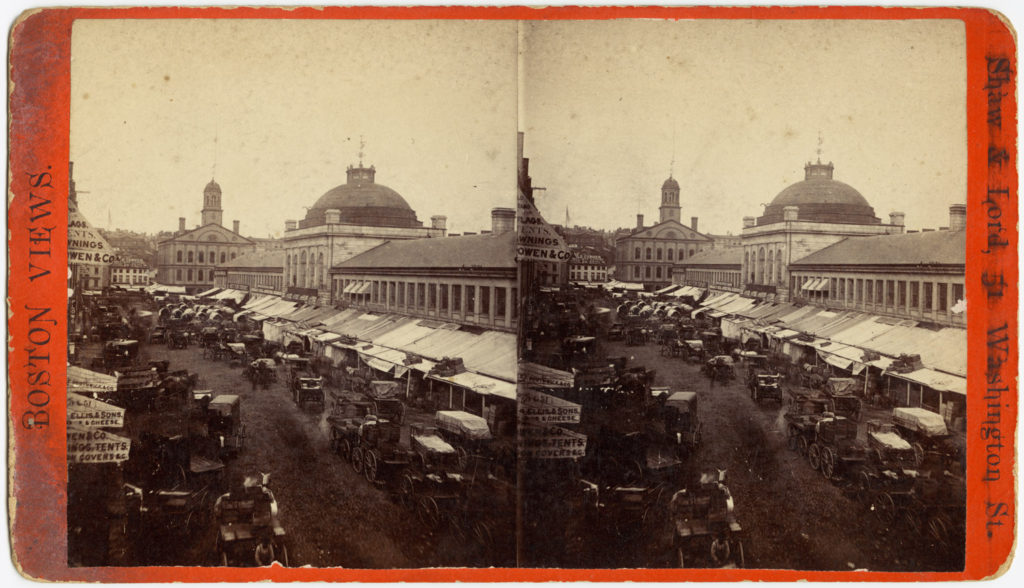

Concentrating on the oldest sections of the city, crushing the determined opposition of old Town elites, he commenced his initiative in his first year in office. He pressed for the modernization of the city marketplace, the over one-hundred year old Faneuil Hall. Included in his plans were a facility in the new marketplace for our beleaguered truckmen, which he defended as”reducing the prices of provisions for the poorer classes”. On his own, the mayor/city acquired adjacent parcels of land as they became available. He retained an architect in 1824 and in that year announced a $1 million redevelopment in which …

the city will buy approximately 142,000 sq. ft. of flats, docks and wharf-rights between Long Wharf and the Town Dock, fill in a substantial amount of that area, and cover it with one huge three-square acre wharf, build six new streets and expand a seventh, and finally erect a granite market-house, two stories high, five hundred and thirty-five feet long, fifty feet wide, covering twenty-seven thousand feet of land. (Crocker, p. 139)

This is today’s Quincy Market. But it didn’t come easily. Attacked on all sides, it was from the get-go a fiscal disaster in the making. Businessmen and voters alike saw increased taxes in their future. And true to form, this first American venture into urban renewal required the displacement of the urban poor who resided in the affected area. To make matters more interesting, the city lacked eminent domain powers to acquire, hold, redevelop, and resell land to private operators–who were then perceived as the prime beneficiaries of the project, at the expense of the poor. But the public works modernization proved attractive to the general electorate–he was resounding elect in the next election. The support came from the truckmen and the people they sold goods to in the city neighborhoods. Quincy Market was perceived as a small business man’s project by the average citizen, a farmers-market if you will.

In pushing the project Quincy asserted the power to issue public debt, a power not included in the city charter–and presumably left to the state. Amid a flurry of “dictator” cat-calls and public outcry, the argued that “in the case of Faneuil Hall Market what possible object of rational apprehension can there be in a debt created for the purpose of purchasing a tract of territory’ that once developed would generate ‘rental’ incomes … wholly within the control of the city authorities’ … only a fool would try to stop this project (Crocker, pp. 140-1).

His success in issuing tax exempt municipal debt for urban renewal, however, did nothing to address his lack of eminent domain authority. Quincy, a lawyer. went to the state legislature and argued in January 1824, for authority to take possession of twenty-four property-owners (including a former Governor John Codman) who refused to sell their parcels, and associated water rights. Stressing that “property is the creature of the social state, where there is no society, there is no property … It follows [that] property is in relation to society a dependent interest. It follows also, that the exigencies or necessities of society are paramount to the rights of property“. Jeffersonian Democrat votes carried Quincy over the top, and he got his approval (Crocker, pp.141-2). In 1826 Faneuil Hall Market opened to the public–and in it the central area was occupied by truckman stalls.

Ironically Logue’s 1960-era urban renewal project touched on both, and, of course, in 1976 James Rouse’s “revolutionary “festival market” separated ED’s physical redevelopment strategy from urban renewal. When the reader visits Boston be sure to stop by Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market/Government Center, it is one of American ED’s magic historical locations.

Quincy’s dictatorial style, his success achieved over the opposition of powerful Federalists and property-holders–his challenge to the municipal status quo and the legacy of debt it left behind–eventually resulted in his loss of the 1828 election. The Boston Quincy left behind in 1829 was rated as the healthiest city in America–and the most indebted. His was the first clear Progressive municipal-level CD strategy, which despite the arrival of hooligan Irish, set the tone for future Bostonian CD Elects for the remainder of the century, giving way to a glorious culmination in the six year, Chamber-Elect-led Progressive “Noble Experiment” that ended with “Boston–1915”.

Take Away

Thoroughly infused with businessmen, and in love with the newly developing industrial capitalism, Brahmin Elect are usually not considered as community developers. In my history, however, this Elect-Wing positioned itself directly over the fault line between our two cultures. They either brought a CD tilt to MED, or the opposite, a MED tilt to CD—depending on the period of time, and the geography. They also founded the initial philanthropic foundations/advocacy institutes as shall be seen in the next module. The Elect in their various styles have arguably been the most powerful, impactful single grouping to play ball in the history of American S&L ED. Today, many call them neo-Liberals. Others, like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon and even George Soros are thought of as Progressives.