Theme 2: Module

Midwest Big Cities–Minnesota: Railroad-Led Immigrant Attraction

For those saturated with thoughts of robber barons, the Populist Movement, railroad extortions imposed on communities desiring access, muckrakers, and an 1887 Interstate Commerce Commission empowered to end/regulate abuses, an Age in which private railroad corporations were arguably the most important External-MED EDO not only seems strange, but outright repulsive. That such an Age endured into the 1890’s might seem incredible. Such is the complexity of history, however. Our post-1850 ICRR case study demonstrated that.

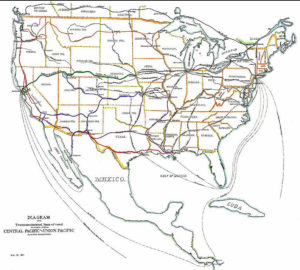

After the Civil War, private (transcontinental) railroad corporations opened up the American West. Less appreciated was the role railroad (as EDO) corporations played in the South, and the Midwest. Also lost in the mists of time was the impact railroad corporations had on cementing Big City industrial hegemony, making Big Cities the national economic sovereign–a powerful dynamic that will be discussed in West and South modules beginning in Theme 2 and continuing in Theme 3.

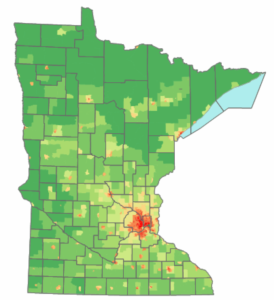

Minnesota is a Big City hegemonic state. In this module I discuss railroad corporation’s role in diffusing the industrial revolution, transporting a workforce/population into an unsettled area–making it possible for Minnesota to join the hegemony, rather than suffer the fate of other neighboring states. Without the timely involvement of the railroad, Minnesota may well have developed later as did the Central States. Instead, Minneapolis and St. Paul developed as Big Cities; Kansas City, with her economic base tilted west, led the Central States, while St. Louis, with her eye toward the east became a true Big City.

Minnesota’s entry into the Big City industrial hegemony, I offer, was made possible because of its timely commitment to “connect its dots” to the national urban competitive system sufficiently early so it could import the industrial revolution–and a entrepreneurial workforce– and integrate its economy into the larger Big City urban competitive hierarchy. This module tells that story, revealing the critical role the Civil War played in its last minute entry into the industrial world. In the nick of time, the Civil War created in Minnesota the ingredients needed for the state to connect itself first to its hinterland, and than to the urban competitive hierarchy. It did so only around 1869. Obviously, the railroad corporation was essential to that task.

Why Did the RR Prove so Important to Minnesota?

The railroad corporation was the cutting edge of the post-Civil War’s industrial revolution’s sector diffusion. It’s easy to understand that as the principal transportation mode of that period, railroad access made diffusion possible. But a Minnesota case study permits us to yet another critical factor. Industries and sectors with which the railroad was closely associated (steel, timber, metal-working/ machine-building, vehicle assembly–and communication, i.e. the telegraph) rode into Minnesota in/on its tracks, wagons, locomotives, and settlements. Railroads built manufacturing and logistical facilities for their own needs. Railroads needed customers to generate revenues to pay off their debt. A railroad corporation is not solely a transportation mode; today it would be considered a cluster-builder, and foundation for a service economy.

In that Minnesota was mostly unsettled until the threshold of the Civil War, the railroad corporation–as it had in 1850’s Illinois–became the state’s principal hybrid EDO responsible for its city-building.This module describes the difficulties encountered by Minnesota in fabricating its hybrid EDO, and jump-starting railroad development. It got off to a very bad start. Importing a by-now essential transportation mode and infrastructure proved no easy task in the wilds of Minnesota.

Without the initiatives of the federal Lincoln Administration, including the Civil War, Minnesota would not have been able to develop that infrastructure in time for its membership as a Big City industrial hegemony. Somehow during the Civil War, immigrant attraction captured Minnesota elite’s attention, and that served as an important “glue” to motivate the state and struggling railroad corporations to join in a common cause. In a sometimes hostile political environment, compounded by cumbersone constitutional gift and loan restrictions that precluded direct state financing of developmental infrastructure, a new railroad developmental finance/business plan had to be innovated. People/immigrant-attraction, homesteading, infrastructure, and city/town-building were critical to that finance/business plan.

Minnesota’s External MED strategy was not accidental, but a conscious private-public partnership between Minnesota State, its railroad entrepreneurs, and the rising business community in St Paul and St Anthony (Minneapolis). Immigrant attraction did not solely populate Minnesota–nor was it ever the only ED strategy employed during this critical 1862-1890 period.

People-attraction seemingly downplays the more conventional business development sector economic base strategy. The cop-out reality is that one requires the other; they are flip sides of the same coin. City-building does not involve picking one to obtain the other. Both go hand-in-hand. What is important to this module is how committed Minnesota was to an immigrant-centered people-attraction strategy. Other states adopted a people-attraction strategy as well–and immigrants were an important target. Minnesota was obviously very successful at it–by the turn of the century Minnesota lead the nation in foreign-born residents

Minnesota

In 1850 a mere eight years before statehood, only 6,000 hardy folk lived there. St. Paul housed 1,100 of them. How? In 1858, it was said St Paul was serviced by 1,000 steamboats–a stopover on the way to the Pacific Coast. Future railroad great, Canadian-born James Hill got his start in 1856 as bookkeeper on a St. Paul steamboat. There was no railroad access to the outside world. The closest was the ICRR, in Chicago, more than 350 miles away.

Minnesota became a state in 1858 on the eve of the Civil War. Civil War era population-economic growth grew the state to 172,000 in 1860 and 440,000 in 1870. It did little to spur urbanization, however–with only 20,000 in St Paul., and 13,000 in newly founded Minneapolis. The potato famine-driven Irish were early immigrants; they were disproportionately urban (St Paul). Minnesota’s early population explosion, however, was rural towns and small cities-based (New Ulm, St Cloud)–cities founded by homesteaders. Even its Big Cities were remarkably little. Including pine trees, everything and everybody had to be transported by river or steamboat. It is my firm unwavering conviction that Mary Tyler Moore first came to Minneapolis by steamboat.

Germans came along with the Irish, but they moved into Minnesota’s agricultural plains. They were early homesteading immigrants, who purchased the machine-tools from startup Minnesota metal-benders and machine tool manufacturers–and they sold their finished product to the flour mills of Minneapolis. It’s more complicated and multi-sector than this, but without the railroad, none of it would have happened and, if Minnesota could not develop its own locally-owned railroads, Minnesota would likely have been a economic satellite of Chicago.

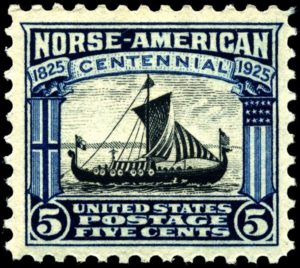

Minnesota was the state immigration created. That it was successful is evident from the nearly 400% increase in state population between 1870 and 1900 (to 1.75 million). As late as 1920, an estimated 70% of the state’s population was either foreign born or had one parent who was. Today about two-thirds of Minnesota residents claim northern European ancestry (Germans, 39%, Norwegian, 17%, and Swedish 10%–toss in the Irish for extra heft). It was Scandinavians that came on the railroad, traveling alongside a later host of other ethnic groups (Polish, Jews, Austro-Hungarian refugees, and Italians heading for Duluth’s Iron Range). Again today, about 85% of Minnesota residents claim European heritage–more than any other state,

Minnesota’s south was agricultural plains and very fertile; but the opportunities and requirements inherent in growing “winter wheat” left its imprint on Minnesota MED. The central and north were forest, thick forest, and the timber/sawmilling sector proved to be the sector that led to Minnesota’s first domestic capital accumulation that invested in other growth startup sectors, such as flour. The east along the Great Lake was mountains, and, as it turns out, full of iron ore and such. Still in the future, the young “port” of Duluth could access Buffalo, the Erie Canal, and New York City. Connecting nonexistent and unpopulated Minnesota urban dots with these entrepots were its opportunities–being a subsidiary of Chicago, its greatest fear. Either Minnesota connected the dots, or Chicago would.

The homebase of early Minnesota was St Paul, the first settled and the reason it became the state capital. The Army (and falls in the river) developed Minneapolis later on.

The reader should assume that despite the silly fiction of a Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, the underlying political, economic and demographic reality is they are two different cities–and usually rivals even if they share the same party affiliation. It is the only state in America where stadium-building is a full-time, bipartisan MED strategy. This case study starts out in St. Paul in the late 1850’s.

Connecting the 1850’s Minnesota urban dots–NOT!

As to pre-1870 Minnesota, you really couldn’t get there from anywhere. It’s on the Mississippi, but that freezes in winter and in parts of it are not navigable.The first prerequisite for successful Minnesota ED was to connect St. Paul–and the state–to Chicago, the closest “here” to St. Paul’s “there”. Get the point? Railroad-led development wasn’t an accident, or imposed on it by railroad capitalist imperialism.

The breakthrough was a rail line that opened in 1854 to Rock Island IL in central Illinois—350 miles from St Paul. From Rock Island it was ONLY 350 miles by steamboat, which consumed thirty hours of unpleasant travel. Yet, within a year, over 30,000 migrants traveled to St Paul (one of whom was a certain Dr. Mayo fleeing Indiana). To encourage more settlers St Paul railroad advocates, seeing opportunity where others see overused toilets, organized “the Great Excursion” and associated PR campaign to draw attention to St Paul and develop support to railroad access to it. No less a personage than President Millard Fillmore participated.

Then St Paul businessmen, railroad entrepreneurs, merchants, startup manufacturers–and state and local political leaders, using the fires of Civil War, forged a successful external-MED strategy to grow the state population and economy by using the state-charter, federal land bank-chartered railroad corporation to promote and attract immigrants, build new towns, and jump-start their economic bases. The nexus/backbone of this public-private strategy was an amended, restructured and updated state/federal railroad corporation.

The Railroad “Scandal” that Plagued Minnesota RR External-MED for 30 Years

The nasty Panic of 1857 bankrupted four startup railroad chartered-companies that had mimicked the Rock Island to Chicago venture and attempted to link St. Paul to Rock Island. Even a state $5 million dollar loan could not save these chartered corporations. Their residue, decade-long defaulted 7% bonds, prompted 1866 state legislation creating a state Railroad Bonds Commission to find a solution. The issue morphed, escalated, and accumulated unrelated debt that compounded the political/fiscal solution.

As chronic problems tend to do, the original 1850’s railroad debt was augmented by unrelated railroad and land improvement infrastructure debt issued in 1841 by the Minnesota Territorial Government, local school systems, and municipalities. A Sinking Bond Commission and Sinking Bond Fund was established to sell state land, the proceeds of which would accrue to the state’s Land Improvement Fund (322 bonds) which would pay off the aggregate bond debt. This did not work. Until a highly controversial solution was fabricated by Governor Pillsbury (owner of a Pillsbury Flour Company) in 1881, the debt politically precluded direct financial involvement by state in developmental transportation infrastructure. The scandal did what gift and loan clauses couldn’t.

So the 1850 Illinois experience was not to be replicated in post-1860 Minnesota. Minnesota did develop an amended state-chartered corporation, but state-recourse public debt for private railroad corporations would not be a part of it. The chilling effect on Minnesota railroad development that resulted forced both public and private to more precisely define their roles and objectives. From that would come, a state-driven immigrant recruitment strategy, targeted land donations, public infrastructure debt for public purposes, and legislative creation of a new state-railroad-corporation.

The private sector was left with the real problem of developmental infrastructure–how to pay for it with unknown future revenues and profits. The railroads found a way.

St. Paul-Minneapolis entrepreneurs … learned the painful lessons of ‘prematurely-hatched railroad schemes’… successful railroads depended upon finding capital enough to build (the railroad), and commerce enough to make them pay (off the debt) … (I)nsufficient products and and consumers constituted barriers that frustrated the state’s railroad-hungry residents. (p. 99)

The Civil War, Lincoln Administration–St. Paul-Minneapolis Lay the Foundation

Federal contracts and association war production spending served as the venture capital to form new startup sectors, allow steamship owners to move into railroad development, promote workouts of older railroad ventures, start new ones, while consolidating in the process the power of the business and political communities behind well-managed and influential railroad companies.

It was they, as “agents of the State, who thoughtfully extended the transportation network into the hinterland to service new homesteaders, and support the expansion of the timber industry. The simple overpowering reality behind this alliance was without it, Minnesota would become a Chicago colony. Te determination was made that only after it developed a local railroad regional infrastructure would the attempt be made to link with Chicago or Rock Falls.

Minnesota’s Republican political elites were vital elements of Lincoln’s winning coalition, and Senator C.C. Washburne was a key member of his inner circle. Lincoln appointed the Senator’s brother, William to assume charge of the transfer of federally-owned pine forests for private timber production (timber in the Civil War was probably as important as steel). William, with considerable sawmill experience opened up sizeable swatches of forest, formed his own corporation, built facilities in Minneapolis, and sent his logs down the river. The capital accumulated by sawmills and timber provided the local venture capital needed to develop other sectors.

Transporting timber/logs caught the attention of the defaulted railroads Eastern investors . Off to the Legislature in 1862. they successfully restructured one (twice) defaulted railroad, transfering all its rights, properties and franchises into a new railroad corporation, with a new board of directors–and injected new investment from NY’s Samuel Tilden, Litchfield Brothers and Russell Sage to build a the area’s first major (seventy-mile) hinterland line. Accordingly, two months after the legislation (April 1862), Minnesota’s first railroad locomotive, the William Crooks, arrived in St. Paul–towed in on a barge powered by a steamboat. It took five years to build the line. Partly the delay was caused by the Dakota Indian War that intervened.

That war brought in federal troops, more contracts, and restructuring of the federal military installation at Fort Snelling in nearby St Anthony. That provided sustenance to a local entrepreneur to form his own shipping company, living off federal contracts, which eventually culminated in another railroad hinterland line into Minnesota’s rich, mostly empty, agricultural plains. Who would use that line into empty acres. A rail connection from St Paul to newly-constituted Minneapolis (it became a town in 1856 and incorporated as a city in 1867) opened only in 1862.

Enter Abraham Lincoln, disciple of Henry Clay’s American System, with the Homestead and Morrill Acts of 1862.

The short story is eighty thousand homesteaders rushed into Minnesota over the next three years (fifty percent of the 1860 entire state population). Pursuing a “once in a lifetime deal: 160 acres of the public domain for an eighteen dollar filing, and a promise to maintain residence for five years” (p. 108). Here was a built-in customer that rode the rails, and incidentally provided the foundation of the state’s agricultural economic base.

A detail was left out of my description of the Homestead Act’s eligibility: the commitment to a five year residency was accepted by the U.S. Naturalization Service as satisfying its citizenship requirement, and gave homestead immigrants a clearly-defined path to citizenship. Between 1861 and 1865 over 800,000 foreign immigrants arrived in the USA; many served in the army, but families anxious to avoid the draft, and the often unfriendly atmosphere of nativist Big Cities, headed for the borderland. Minnesota got more than her fair share. I think I know why.

In the Midst of the Civil War, Minnesota Embarks on Immigrant-Attraction and Transcontinental RR

Immigrant homesteading was quickly seen as a vital piece of a State people-attraction strategy. Ignatius Donnelly, an Irish immigrant himself, was Minnesota’s Lieutenant Governor at the time. Elected to Congress in 1863, he proposed legislation for an idea that had gathered considerable steam in his adopted state. In an address to the House in 1864, he presented the romantic, if politically incorrect rationale for a national immigrant-based people attraction strategy:

with nearly one billion [acres] of unsettled lands on one side of the Atlantic, and with many millions of poor and oppressed people on the other, let the people of the North (the Union) organize the exodus, which must come, and build, if necessary, a bridge of gold across the chasm which divides them, that the chosen races of mankind may occupy the chosen lands of the world (Jocelyn Wills, Boosters, Hustlers,and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, p. 109).

In that Donnelly was a strong supporter of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and active in its affairs, he may be tolerated for his politically incorrect phrases, but the advantage Minnesota held for immigrant attraction was seen very early on in the State by its political and business elites. In 1864, Minnesota State set up a Bureau of Immigration, and immediately began an aggressive immigrant attraction recruitment initiative. It did so under the leadership of its Senator Henry Rice and ex-Governor Ramsey. The Bureau was intended to partner with railroads, specifically a federal land grant corporation railroads like ICRR. And where did that federal land grant railroad corporation come from?

Transcontinental RR–Along with the Homestead and Morrill Acts, the Lincoln Administration secured approval for the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862. That Act incorporated the Union Pacific Railroad, infused it with federal lands and considerable other resources/powers, and sent it off to link up with a second land grant railroad which together would build the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. The Act actually envisioned a total of three transcontinental routes–not one. The one attracting our present attention was the northern one that crossed Minnesota from Wisconsin’s Lake Superior, and extended to the Pacific.

When the northern route’s first venture failed, Senator Rice seized the lead, proposed a federal land grant chartered bank infused with sufficient financing to fund it from Minnesota to the Pacific. On July 2, 1864 Congress approved legislation which created “the Northern Pacific Railroad Company (NPR), chartered also in Wisconsin, which would be empowered to build a line from Lake Superior to the Puget Sound. Rice’s State Immigration Board was intended to attract immigrants from the new line to Minnesota through an aggressive promotion campaign, well-developed collateral materials, guidebooks, with specific attention to Minnesota’s merits to form an “agri-business”, touting St Paul and Minneapolis as emerging manufacturing opportunities in the “New Northwest”–as well as a healthful climate (pp. 112-3).

An ambitious start to be sure, but NPR ran afoul of this hostile railroad realities of Minnesota, and while the attraction campaign would take root, the NPR transcontinental railroad became a vehicle to a scheme to restructure yet another of the infamous defaulted railroad. It didn’t work, and would languish until the 1873 Panic put an end to its miseries through bankruptcy. In short order during the Panic, a rising entrepreneur, well-versed in transportation, maneuvered his way into a controlling interest in NPR. James Hill, the robber baron, would make NPR into a transcontinental railroad extending to the Puget Sound–and other lucrative locations as well.

With all the irony one can muster, I might also mention that it was NPR’s fate to run afoul of Teddy Roosevelt, who in 1904 “busted” this federal land grant chartered corporation, which he believed had been transformed into a massive monopolistic pillaging “trust”–NPR was the core railroad in the trust-busting Northern Securities Case.

So beware of what you ask for.

Minnesota Develops its Hinterlands

In any case, Minnesota’s population explosion and federal railroad legislation triggered all sorts of Minnesota railroad startups and restructurings. Each newco was chartered by the state legislature and each connected St.Paul with its hinterland, including the dynamic Red River Valley (bordering on the Dakotas) hinterland. Another restructured the bankrupt Southern Minnesota RR Company and started in 1864 a newco, the Minnesota Valley RRR (MVR). That restructured railroad proved to be the “engine that could”.

MVR had ambitions, was well-connected to steamboat ownership interested in divesting itself from steamboats into railroads and offloading steamboat cargos and freight. Its directors purchased the half-million dollars of capital stock authorized by the state legislation. Speedily MVR built several additional lines from St. Paul, and in 1866 opened a new line to St Cloud. By 1867, having taken over the bulk of the state’s freight from steamboats, MVR was ready to move south–toward Chicago and the competitive urban dots.

MVR formulated a strategy to connect Minneapolis sawmills/lumber to southern Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska–Minnesota was ready to finally link up with market areas serviced from the Chicago behemoth railroad hub. By 1868 it completed ninety of the one-hundred and twenty miles to Sioux City. In the same year, the state legislature created yet another state-chartered railroad corporation (effectively controlled by MVR), the Milwaukee and St. Paul RR which purchased the assets of yet another bankrupted railroad. Issuing their own $6 million dollar stock offering, to construct a line to Eau Claire WS, they also incorporated yet another state-chartered railroad, the St Paul and Chicago. Minnesota was going to connect itself to the urban competitive hierarchy–not be connected to it by outside railroads.

To ensure that happened, the state legislature in April 1869, reorganized and refinanced MVR (and its multiple subsidiaries) into the St. Paul & Sioux City RR–divesting the ownership of the flour mills in the corporation which then joined forces with the restructuring transcontinental NPR. New investors and business leadership injected into the boards–and two competing, well-funded, locally-controlled railroad corporations came out of the legislative melange. At first the reconstructed Sioux City line was successful. In September, 1869 the Sioux City’s first northbound train arrived at St. Paul–the southern link had been completed and Minnesota had built its first (albeit roundabout) connection with Chicago. (Jocelyn Wills, Boosters, Hustlers,and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, pp. 132-4)

The Immigrant-Attraction Strategy

Included in that state-led restructuring, supported actively by Senator Rice, were provisions which tasked the State Board of Immigration to work with the new competing lines that would link St Paul with Chicago, and extend to the Pacific.

With the legislature’s support, the SP&P (MVR newco Chicago corporation), the (immigration) Board planted newly authorized agents in Milwaukee and Chicago, their salaries jointly funded by the state and the railroad companies. State immigration agents tailored their advertising pamphlets to attract the “right sorts of homesteaders: displaced agricultural and factory workers from the British Isles (which included Ireland), northern Europe, and the more populous regions of the United States, those anxious to ‘settle upon fertile prairies and become prosperous and influential citizens’. (Jocelyn Wills, Boosters, Hustlers,and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, pp. 116-7)

Jocelyn Wills asserts this joint venture meant the State, its Board of Immigration, and the Minnesota’s railroad and business ownership had committed to a long-term strategy of primary importance and value to the the State and its Businesses–a partnership based upon the belief that “the remoteness of our State from the East, and the cost of transportation render the development of [commerce and] manufacturers an objective of the highest importance“. (Jocelyn Wills, Boosters, Hustlers,and Speculators: Entrepreneurial Culture and the Rise of Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1849-1883, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005,pp. 118-9)

Colonization: James H. Hill and the Northern Pacific Railroad Company

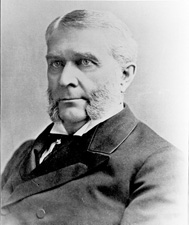

NPR, under James Hill, got its act together. Hill started in steamboats, warehousing and shipping, moved into the early railroads ventures described above, and assembled a local coal monopoly–all of which carried him through 1870 and made him a fortune. It was the 1873 Panic that allowed him to use his capital to acquire failed railroads. He was among the first entrepreneurs of a younger generation that had been “educated” in Minnesota’s school of hard knocks.

Most known for his Great Northern Railroad, he actually owned, managed and controlled many others. In the late 1870’s he embraced a plan to construct a railroad(s) from St Paul to the Pacific Ocean–“Hill’s folly” it was called. Later allied with J.P. Morgan, he extended his railroad empire to access directly Chicago. His was the railroad empire than Teddy Roosevelt was determined to “bust”. Whatever TR thought of him, Hill was a favorite son of St Paul, a life-long resident, and its principal power-broker. An Irish machine political system, and the local Catholic Church (headed by famous bishop John Ireland) were his chief beneficiaries.

An immigrant himself, Hill took the ICRR model and applied it to northern European immigrant attraction. The Northern Pacific Railroad Company (incorporated in 1864) in 1866 (four years before he laid its first track) called for the re-authorization of the State’s Bureau of Emigration “for the purpose of settlement of the lands of the company”. He expressed a willingness to send his own agent (William Rowland) to Germany and “other parts of northern Europe” if the state would designate the Rowland as its agent. So In September, the Governor provided an official letter as “Special Commissioner of the State of Minnesota to the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition. Hill, St Paul, and Minnesota commenced their immigrant attraction strategy Harold Peterson, “Early Minnesota Railroads and the Quest for Settlers”, Minnesota History Magazine, March 1932, pp. 25-44, quote on pp. 27-8.

The state Commission of Immigration—made permanent in 1869–formalized the State’s immigrant attraction advertising program. The legislature appointed Albert Wolff as its Commissioner, and he hired a network of agents to work with/assist immigrants in St Paul, Chicago, Milwaukee, New York City and Sweden and Norway. An aggressive, very sophisticated advertisement–awareness program promoting Minnesota and its regions[ii] proved very effective. Unlike the state foreign offices of the post-1980’s Transition Era which attracted firms and assisted American exports, the late 1860’s attraction target was people.

As early as 1871, Board of Immigration in its annual report, made no secret that its agents success was made possible by the assistance of “experienced railroad men who served without expense to the state board”[iii]. Subsequent reports documented that much of the Board’s expenses were paid by funds from railroads. Minnesota and its railroads were now engaged in a partnership to populate the state, build cities, and set up regional economic bases. The content of this attraction strategy stressed Minnesota’s superior public health, a consequence of its favorable harsh climate. Huh?

Gilded Age Big City public health concerns were huge and personally devastating. Smallpox, TB, typhus, malaria and a host of influenzas came from their horrendous unhealthy water infrastructure. A total lack of sewers and filtered water meant that periodically major cities were confronted with a crippling epidemic. Whenever one struck, residents enmasse fled the Big Cities. What does this have to do with railroad immigrant attraction?

One of the first themes that Hill’s railroads embraced to promote colonization was the health benefits supposedly enjoyed by frigid Big Cities–especially Minnesota’s. Preposterous to today’s reader, post-1860 collateral material stressed health benefits associated with new virgin land. Minnesota’s Siberian climate killed mosquitoes, and mosquitoes bred malaria. Tuberculosis was a horrible and slow killer, and no one in these years really understood what caused it. Extremes of heat and cold were believed to alleviate symptoms and prevent its spread. Minnesota benefited from this belief. For example, this belief had earlier prompted an American self-educated “doctor” to move to Minnesota. Fleeing a Lafayette Indiana malaria epidemic, Dr. William W. Mayo moved first to St Paul, and eventually settled in Rochester Minnesota in 1863. What followed, of course, is its own story.

The beauty about health marketing was that it drew in middle and professional classes who could afford to move, and whose skills were desperately needed.

The railroad/State EDO partnership set up an overseas HQ office in London, from which it operated a number of sub-agents who operated in the various nations of northern Europe. Native speakers were hired and collateral material was in the native language. Subsidized travel agreements were signed with steamship corporations, port administrations, and railroads to in effect act as the immigrant’s travel agent. Costs were subsidized (often financed through a railroad loan). The quality of accommodations reflected the railroad’s cost minimization bias, but interim housing was available for free. Agents were waiting at the docks when the immigrants arrived and at each major transportation node where a layover was required. Like today’s airlines (HA!) reasonable baggage was free and arrangements were made by the railroad to clear it through Customs.

The advertising program was sophisticated for its time, although it lacked websites and apps. Pamphlets, how-to and travel books, newspapers articles and advertisements, circulars, and an intensive lecture series in targeted communities and populations were its principal methods. In most European cities “bureaus of information” were set up and collateral material were available. Attendance at the various Expositions was commonplace. Obvious then, less so now, the key to the transaction was the job or farm waiting in Minnesota. This was without doubt, the most sophisticated aspect of the attraction partnership.

Rural immigration with the end-point being a farm meant railroads provided the prospect detailed, sometimes exaggerated, but often fairly reliable information, secured through survey results from the destination area. Soil analysis, the mechanics of crops and soil cultivation were provided to the target in Europe. Land was cheap/subsidized, and usually purchased, not by a mortgage which was nonexistent in the Gilded Age, but by a railroad loan. Many railroads offered the European prospect an “inspection” of the farm prior to purchase free of cost—this was not typical, but neither was it commonplace. More often the prospect was offered a discount in cost (or a credit for the fare) if the customer actually bought the land. Usual terms were 10% down, and seven annual payments at 8% interest. Also, land deals could include a reduced time-specific freight rate for future production.

All this was usually financed through railroad bond-issuance. Each railroad assembled its own “package” and competed against packages offered by other railroads. Railroads offered technical assistance to apply for any relevant public programs—i.e. homesteading deals offered by state and locals. All this sounds too good to be true—and one wonders if it reads better than it was experienced—but it is reasonable to believe this was no paradigm of deception; for its day a fair deal, if one had low expectations. Gone was the “coffin ship” experienced by the early Irish and German immigrants. Some level of customer satisfaction was necessary if the program to continue to attract new customers—and, remember, outstanding bonds needed to be repaid.

Segue Way

The immigrant attraction strategy/program proved extremely successful. It was, however,only one aspect or dimension that constituted a package of External-MED strategies carried out by the state/federal-chartered post-Civil War railroad corporation. The next module expands on these strategies and details city-building, and introduces the topic of industrial attraction. It also fleshes out homesteading attraction which was critical to Minnesota, Central, and Western states. Most importantly, the next module presents the financial/business model that justified the railroad corporations public service to its private investors–the need for which resulted from the constitutional gift and loan clauses which by this time had become standard in state constitutions.

Footnotes

[i] General Statutes of the State of Minnesota in force January 1891; https://books.google.com/books?id=Ej8wAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA200&lpg=PA200&dq=1881+Minnesota+railroad+bond+issue&source=bl&ots=mfOw4CXkO9&sig=nPVt0sA0j8C7jKtNQyu2sX03m9g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJ4_f-XWAhWh7oMKHaDHCMMQ6AEIMTAC#v=onepage&q=1881%20Minnesota%20railroad%20bond%20issue&f=false

[ii] Harold Peterson, “Early Minnesota Railroads and the Quest for Settlers”, Minnesota History Magazine, March 1932, pp. 25-44, quote on pp. 27-8.

[iii] Harold Peterson, “Early Minnesota Railroads and the Quest for Settlers”, Minnesota History Magazine, March 1932, pp. 25-44, quote on p.29.

[iv] Carey McWilliams, Southern California: an Island on the Land (Peregrine Smith Books, Salt Lake City, 1973), p. 100.

[v] Harold Peterson, “Early Minnesota Railroads and the Quest for Settlers”, Minnesota History Magazine, March 1932, pp. 25-44, quote on p.41.

[vi] American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/essays/1801-1900/the-iron-horse/railroad-towns.php

[vii] See the early evolution of the American industrial park in Coan, As Two Ships, pp. 134-7.

[viii] Coan, As Two Ships, pp. 228-233.