Civil War and Reconstruction:

the Hinge Connecting Antebellum South to Redeemer New South

Organization of Module

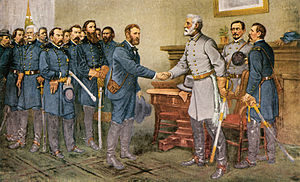

The Civil War was a “turning of the page” in our nation’s history–and American ED turned with that page. Assessing the war’s impact, however, is not a simple intellectual, rational, professional Spock-like exercise. The war created emotional baggage that infused into politics and policy for decades after.

By the time that baggage had burned itself out, the decisions made by policy systems had institutionalized themselves, and had become a new foundation on which subsequent policy would be built. The problem, which we shall make over the next three modules, is the “peace” that the North imposed on the South through Reconstruction was both incomplete, and polarizing. The South was not without its mistakes, but the North was the victor–and to the victor belongs the blame.

To understand how the “peace” failed–and to sense how and why affairs evolved as they did, requires us to go beyond simple professional strategies, tools, EDOs and the like. These are only policy outputs of policy systems forged in the fire of war and the “peace” that followed. Our attention in the next three modules will be focused on the policy systems that emerged from the chaos and defeat that was the 1865 South. That war generated much more than changed policy outputs, it created policy systems that were built around the emotions, memories, frustrated hopes and newly-generated fears. We call all this environmental baggage “emotion”. Baggage shaped a distinctive southern policy system which we label “Redeemer”. The North left Reconstruction behind, turned inward, and constructed “Gilded Age” policy systems. The reader might suspect a stark regional distinction in economic development is sure to follow.

Fragile and diverse, yet politically unified in a “Solid South” against its northern enemy, southern Redeemer policy systems fabricated their own internal policy decisions, with ED a centerpiece policy area. In the remainder of this theme I hope to capture some of that diversity, centrality–and fragility and how it affected our national ED history. To say we conduct ED in accordance to how “we shot in 1861” is an oversimplification, actually a gross exaggeration, but we need to better appreciate that the Civil War generated lasting consequences that persist into our Contemporary Era.

Too often historical analysis divorced from the then-contemporary reality, conveys facts and time lines, but not the pain, joy, hope, fear, frustration and the yin and yang that comes with actually living through tumultuous events. That emotion entered into policy decisions, and shaped the course of southern ED to the present day.

Then-contemporary decision-makers saw, and felt things differently than current readers. That the antebellum South had been crushed and was totally devastated by the Civil War is obvious today. What that meant to those who lived through it, had to confront its daily realities, and then devise a path to recovery is another matter entirely. A fair assessment requires injecting an emotive element into one’s analysis; In that way we can better sense the atmosphere that impacted decision-making. That, however, is easier said than done. Whether one happens to be from “the winning or losing side” another layer of emotion creeps in to one’s rationality. The amazing thing about the Civil War is the emotion is still alive today–and quite impactful.

In this module we start off with the devastation that was the post-Appomattox 1865 South. The sheer amount of devastation needs be appreciated, if only because rebuild and repair were to be the principal tasks of ED in any future southern policy system. In the South’s case, an added dimension was the need to confirm, repudiate or diversify the now-destroyed southern agricultural economy and economic base. Southern economic development decision-makers had to make a choice even before they started their rebuilding and repair. Civil War defeat invited a serious rethink regarding its economic base.

The problem for most southern decision-makers/elites is that, for up to a decade in some states, many southern elites were excluded from either the decision, or post-war rebuilding by northern-imposed “Reconstruction” policy systems. The North during Reconstruction imposed an entirely new policy system on the South, and for all practical terms, those defeated had no real say in that. Whatever these Reconstruction policy systems did in regard to ED, rebuild or repair the South, or whatever choice they made on the future direction of the South’s economy acquired an emotional connotation from those left on the margins of decision-making. Eventually, those left on the sidelines reentered politics and policy-making, and when they returned they carried a great deal of emotional baggage, including a wistful longing to return to the good ole days.

I mention this only because that emotional reaction to Reconstruction policy systems–and their ED decisions–shaped southern ED for a century after. To blindly apply Spock-like professional rationality or contemporary political correctness to this situation will likely lead us astray.

Our focus is on economic development. At this critical juncture emotion, values, morality, and other irrational aspects inherent in policy-making became paramount and primary. However disturbing, they must be acknowledged and integrated into our analysis.

The long-term consequences of these decision, given the soon to be discussed weaknesses of Reconstruction decision-making, meant the South continued its own distinctive, isolated, pattern of political and economic development much as it had done during the antebellum/Early Republic years. It would need a Second Reconstruction to change that.

That the effects of Reconstruction Era decision-making lasted for a century–and still continues–means this period was a turning point and arguably a major driver in the future evolution of American S&L ED.

In any event, it was certainly the key single driver of future southern ED, and that meant American S&L ED was destined to be “regionalized”, with the various geographies of the continental United States on different time lines, historical experiences, as well as their own unique location assets and weakness. In this decentralized environment, cultural forces could more easily insert themselves into the fabric of regional distinctiveness. Ironically, in this reality, the South’s preference for state’s rights over national hegemony in S&L ED policy-making was victorious.

Accordingly, after considering the War’s devastation, this module spends a great deal of effort outlining two Reconstruction Era dynamics (Reconstruction policy systems and their troubled MED strategies) whose heritage determined the fate of the post-Reconstruction southern ED.

Unconditional Surrender: Economic and Cultural Effects of the War on the South

During the war one out of four military age southern white males died. An additional 200,000 were permanently maimed–18% of the population and 36% of those over 19 years of age. The war destroyed white yeoman farming, leveling as well as the planter-dominated officer class, creating a lost generation and a bitter “lost cause” mentality as its immediate heritage.

Prior to the war the South had a bimodal wealth distribution … the classic planter [fifty or more slaves] … only about 8,000 families … [made their states among] seven of [the nation’s] ten states with the highest per capita wealth …. However, since 70% of southern families did not own slaves, the 1860 per capita income of the region was only slightly ahead of the north central states, and well-behind the average northeastern state. It took eighty-five years for the South’s per capita income to regain its below average 1860 percentile ranking. …. Excluding the total loss in the value of slaves … assessed property values at the end of the war were more than 40% lower than in 1860. [1]

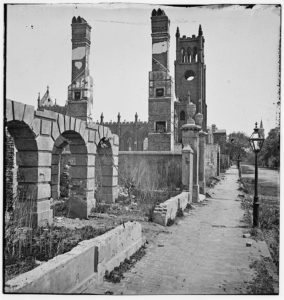

As the reader today scans newspapers and sees images of war-torn destroyed cities and countryside of the Middle East, the 1865 South was no better, easily comparable to the devastation of WWII 1945 Europe. Phillip Leigh tries to capture the extent of devastation–and its persistence into the 21st Century:

The war had destroyed two-thirds of southern railroads and two-thirds of the region’s livestock … Steamboats had nearly disappeared from the rivers … since their protective levees had been destroyed, thousands of square miles of Mississippi delta cotton lands were overrun with briers and cane thickets … By 1870 southern bank capital totaled only $17 million compared to $61 million in 1860 … the region’s currency in circulation dropped from $51 million to $15 … Not until 1879 did cotton production return to pre-war levels, … by 1900 the South had barely recovered to the level of economic activity prior to the Civil war. [2]

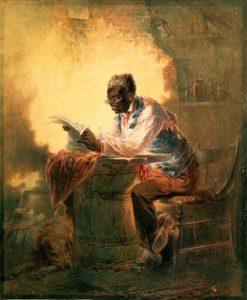

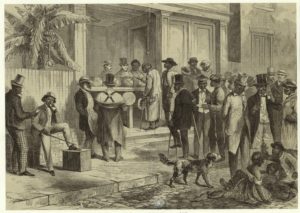

What transportation infrastructure–and factories–the South possessed were destroyed. Many of its few cities burned down. Without transportation infrastructure, it was expensive and time-consuming to get interior-grown cotton to southern ports. For an export-based agricultural system, relying on King Cotton global markets, already challenged by Civil War disruptions, the South soon faced economic ruin. As for consumer disposable income, it was non-existent. While ninety percent of American Blacks still lived in the South in 1870, former slaves, now Freedmen/women, got rights, at least initially, but not money, education, or power. While emancipation meant victory in civil rights and the potential for individual liberty, Reconstruction would do little for their economic future.

The South’s chronically-depressed economy trapped its population, both white and black, into an unendurable and seemingly perpetual rural poverty. Southern white per-capita income, $125 in 1857, never recovered until the 20th Century. In 1879, it was only $80. If the North, despite its immigrant inequality had entered into Gilded Age prosperity and economic growth, the South suffered from pervasive economic stagnation characterized at best by grudging incremental, if volatile, normalcy that characterized the gradual restoration of the cotton/agricultural-dominated economy. That difference was fundamental to our ED history. To even imagine the post-1870 southern economic developer confronted the same set of problems as did his northern counterpart, is, simply put, ridiculous.

At war’s end, Reconstruction was imposed on the South–inserting military rule, terminating Confederate constitutions (which had replaced older Early Republic ones), and, despite its future Jim Crow limitations, ended slavery, and in so doing restructured the old-style pre- Civil War “Tara” plantations on which the South’s pre-Civil War agricultural base rested. In that the plantation was the South’s equivalent to the northern factory, the foundation of the South’s agricultural economic base was profoundly disrupted. James Cobb describes the impact of the Civil War and subsequent Reconstruction on the most prosperous and productive Cotton Belt region: the Mississippi Delta:

The upheaval of the Civil War and Reconstruction destroyed the Delta’s prospects as a large slave-holder’s paradise and confronted its planters with the reality of their dependence on a huge black labor force suddenly free to exert its newfound economic leverage and exercise its recently acknowledged political rights as well … [Even post-1875] redemption brought no immediate restoration of planter hegemony … Freedmen continued to use demand for their labor to secure more advantageous terms for their labor … Not until the 1880’s when federally-funded levee rehabilitation and privately financed railroad expansion triggered a land and population boom, did the region begin to reclaim its antebellum identity as the undisputed domain of the planter [3]

Two Reconstruction Era Dynamics that Shaped Post-Reconstruction Southern ED

The remainder of this module concentrates almost exclusively on two Reconstruction dynamics that decisively shaped the post-Civil War South. The first dynamic, the reconfiguration of the antebellum state and local policy system into a Reconstruction policy system, started the South down a path that has led to our present-day. The key Reconstruction “change” was that it emancipated the slaves, extended to them the political franchise, in so doing destroyed the antebellum southern state and local policy system–and by intention fundamentally damage the plantation, the functional equivalent of the North’s factory, as the chief productive unit of the southern economy. Federally-imposed Reconstruction essentially shuffled the South’s political and policy deck of cards–and then walked away, leaving southern decision-makers to play the cards dealt to them.

The second dynamic was the decision/actions made by the transitional Reconstruction policy systems. Whatever its merits they decided to encourage northern-style industrial and commercial development, to diversify away from the now devastated agricultural economic base. This was a state and local decision by Reconstruction elites–not a national policy. That S&L strategy rested principally on scarce southern resources, and limited, novice governmental expertise and capacity, by a policy system that was obviously transitional.

Coincident with the new urban Reconstruction policy systems was a refugee-fueled post-Civil War urban migration, which for the first time in that region’s history, promised some sort of balance between the city and countryside. In fundamentally disrupting southern agriculture during the war, the North had opened the door for a new level of government to become a meaningful, and more prevalent, player in S&L ED. The War opened the door to future southern modernity that in its own good time could lay the foundations for a future rise of the South.

(1) the Reconstruction Era State and Local Policy System

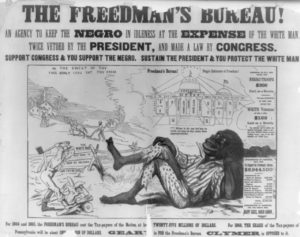

Reconstruction was the equivalent of a southern political revolution. There was no formal attempt to conduct an economic one. Congress rightfully determined slavery had to end whatever its consequences. The Freedman’s Bureau was as far as the North went in providing an administrative vehicle and policy/strategy to liberate slaves and manage their political and economic affairs.

In effect, the Bureau was a federal CDO intended to enforce African-American emancipation, extension the franchise to them, and to tentatively integrate Blacks into the local economy–using limited homesteading programs drawn from bankrupted plantations. Whites were left to their own devices.

In the handful of years and funds allotted to it, the Bureau could not have achieved success. Limited to Freedmen, the Bureau did nothing for white yeoman farmers, the majority of the South’s population. With no where to turn, they sharecropped, fled to the cities, or continued small household farming, transformed from hardscrabble to bare subsistence. The economic distinction between white yeoman farmer and black Freedmen was reduced to the color of their skin. As far as the economy went, both races were on their own. The federal government, after 1876, “had left the ED office”.

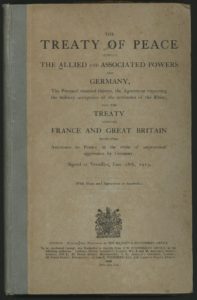

Congress never contemplated anything like a post-WWII Marshall Plan. What they intended, and got, was a WWI Versailles-style revenge, retribution, and moral reform.

By 1865, the southern economy for all practical purposes had degenerated into an all-encompassing Depression, almost certainly more severe than the 1929 Great Depression. With plantations burned and debt-ridden to the point of bankruptcy, its owners often disenfranchised, lacking a workforce, and foreign markets disrupted, the agricultural economy was in crisis. Except for the Union Army in the early desperate years of Reconstruction there was little that provided political cohesion to any southern policy system. The Reconstruction South was the closest this nation has come to regional anarchy thus far, and that desperate time generated emotion that would fuel subsequent “Redeemer” policy systems. As the Depression left its emotional baggage on generations to follow, so would these catastrophic years. The political reaction that shortly followed was generated by a Reconstruction strategy that completely neglected the South’s economic reconstruction.

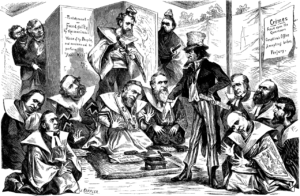

Post-Succession policy systems coped until the 1867 Reconstruction Congressional Phase commenced. The Radical Republican Congressional core strategy equaled the political liberation of slaves, which was duly implemented through the cumulative impact of three newly-approved articles to the Constitution.

Based on conformity to these new articles, Congress devised a path to re-admit Confederate states to the Union–which, because any future the South had, meant rejoining the Union, generated yet another round of new state constitutions and a series of elections for legislatures, governors and city councils. Reconstruction was designed to be temporary and transitional. The North was already moving on, into its greatest period of industrial growth–the Gilded Age.

Accordingly, individual each southern state constructed its version of a new political order, and a new set of state and local policy systems. By 1876, all but three had been readmitted to the Union.

the Reconstruction Policy System

During the Reconstruction “presidential phase” the conquered former-Confederate governments lingered on, sharing control and administration with the federal army. This was truly the most desperate of times, and governance was chaotic, often violent, and depending on the state, the South descended into near-anarchy. As constitutional amendments were approved over the next several years by the Congressional Radical Republican post-1867 majority, a Congressional phase, including attempted impeachment of the President took over administration of Reconstruction.

The inclusion of Blacks as meaningful participants in politics and the economy obviously turned antebellum southern state and municipal policy systems upside down. Election of Freedmen meant, at minimum, whites no longer controlled southern S&L policy making. High-ranking Confederate officers and officials were denied suffrage, and southern war debts repudiated–bankrupting many southern financial institutions and property/plantation owners–removing for better or worse previous political elites.

In Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina (the Black Belt), Blacks were a majority in constitutional conventions, and governments that subsequently were elected. Replacing antebellum elites were a coalition of southern “Whigs”, i.e. Republicans, Black Freedmen, northern emigres (aka “carpetbaggers” who were both honest and corrupt), and opportunistic southern businessmen (called scalawags). Swept into victory in southern cities, towns and states these new elites constituted the new governing class of the Reconstruction South.

(2) Reconstruction Era MED

Victorious, the Reconstruction coalitions after 1868 won S&L elections, approved new state constitutions, and ultimately assumed responsibility for state and local governance. With the Army unwilling to “govern” states and cities, these Reconstruction policy systems, described above, conducted what passed for policy-making. Depending on when their state returned to the Union, they managed the affairs of state and cities until the transition.

In these desperate times, hinterland migration to the cities–displaced refugees is what we would call them today– repopulated burned out cities. The 1870 census surprisingly revealed southern cities had increased population since 1860. In 1860 the South’s urban population was 9.6% (compared the Northeast’s nearly 36%). By 1870 southern urbanization had increased to over 12%. Stagnant during Reconstruction and the ensuring Panic of 1873, the South after 1880 urbanized incrementally every decade to the present. It was the War that first jump-started serious southern urbanization.

From this point on, city-building and urban growth incrementally transformed the South and created an alternative to the agricultural economic base. Reconstruction and Redeemer urban policy systems, developed their own responses to desperate realities, the need for physical reconstruction, and economic base-building. As we shall see a new commercial and industrial business class would emerge.

Not surprisingly, cities prized MED and placed it exceedingly high in their policy agendas. Southern cities became a vibrant source of innovation and serious policy-making and their needs and perspectives pointed them in a different direction than their northern counterparts–and often their Redeemer allies in southern state legislatures. Whether they had sufficient capacity to actually change their economic future varied greatly. During the antebellum South, the principal force and policy-maker in southern ED was the state–and only a few major cities (New Orleans, Atlanta, Nashville) could reliably advance their interests. Still, after the Civil War and Reconstruction, southern cities evolved into ever more impactful players in the making of southern ED policy. This period was a game-changer.

Reconstruction State legislatures and governors, and their pathetically small bureaucracies, were for all practical matters brand new–with little to no expertise. Legislative majorities were loosely acquired, governors were weak, and “opportunities” were plentiful. To the extent there was any “plan”, it was to get the Army out, and to be readmitted to the Union. In short, one can view these Reconstruction policy systems as transitional–which justified a “get what you can, while you can” mentality (In the North ethnic political machines described this as “I saw my opportunities and I took them“).

As any textbook will be glad to tell the reader, Reconstruction, as far as honesty went, was seriously lacking. There are any numbers of corruption stories to tell, and because MED was so high on the policy agenda, MED was a frequent target-victim for corruption. To provide a flavor, a below section describes how several state’s handled railroad developmental infrastructure. Unfortunately, corruption was woven into a “Deborah Stone-ish story” that cemented into a lasting legacy which consumed the South S&L policy-making for the next half-century or more.

That legacy, for our purposes, had two elements. The first was that, often without much thought, Reconstruction cities/states attempted to “industrialize”. In response to carpetbaggers, opportunistic scalawags, and legitimate opportunities from northern investors, cities in particular, provided considerable assistance to startup businesses, factories–and railroads. Given the short-lived and transitional nature of Reconstruction, much of Reconstruction Era MED went bad; flagrant corruption and scandals galore followed. On top of this the Panic of 1873, like all panics described in this history, was worse, and more long-lasting than previous panics, exacted additional devastation, including fiscal deficits and defaults on southern policy systems. All this was replicated at the state level. Millions of dollars of state/local debt accumulated or was swept under the rug.

The new Redeemer governments were left “holding the bag” when they took over. and in very short order until Reconstruction ended, and Redeemer governments took over.

When Redeemers took over in the 1870’s and 1880’s, the planter class was the most organized, and respected element in their coalition. Plantation owners naturally had little desire to industrialize, and when confronted with having to pay the piper for Reconstruction defaults they not only enacted the most severe gift and loan clauses into their state constitutions, but they repudiated a number of business incentives, tax abatement in particular. Despite the urban myth these Redeemers were determined to steal, beg and attract industrial firms, they wanted as little to do with private business, and industrialization, as possible. They wanted to redeem the South from the corruption and business influence peddling that dominated Reconstruction. They wanted to separate private and public spheres of action–through gift and loan clauses.

To be sure planter-dominated Redeemers believed deeply in limited government providing limited public services–it was part of the cultural DNA–but the need to pay for bond defaults, and their absolute unwillingness to raise taxes, meant state–and local–governments were crippled by budget cuts that effectively meant even fewer services and less government. This budgetary, public services, and fiscal legacy persisted well into the 1890’s.

Redeemer State governments in particular were almost taken out of ED policy-making, but equally important, out of public education, and even roads and bridges. It was in this period, that the infamous ‘southern business climate” became institutionalized, and was instilled into many southern electorates and ED decision-makers. That culture’s chief inspiration was to keep taxes low–not attract business. Tax increases became the third rail of southern politics, and whatever role state governments might have played in addressing southern poverty and economic devastation fell to the wayside. The midwife of the traditional southern business culture was Reconstruction Era corruption.

External MED: Railroads–Scandals

It has been said that corruption flourishes when there is money to be protected, or money to be made. In terms of MED, the obvious potential in financing Reconstruction railroad infrastructure (financing, construction, operation) to integrate the northern economy with southern agriculture for example was an example of money to be made. The South lacked private capital, and that meant state and local government had to step up to the plate if railroads were to be built. It did so with disastrous consequences. Railroad scandals were common, and dominating late and post-Reconstruction periods. These scandals did little to increase railroad infrastructure, or the reputation of government and politicians and much of southern MED was privatized for the rest of the 19th Century.

Governor William Hughes Smith who presided over this mess–a former Union soldier who marched with General Sherman

Every southern state got involved with railroad development. Atlanta was awash in railroads but it survived Reconstruction without serious blemish. Alabama, however, offers an excellent example of how things went bad. In 1867, the state legislature authorized the governor to issue railroad mortgage bonds at the rate of $12,000-16,000 per mile, so long as the railroad connected to another state. That meant laying at least twenty miles of track in another state. There was no market analysis required, so demand and future traffic did not enter the calculation for public assistance. The state would issue a tax-exempt bond, secured by a first lien, and transfer proceeds to the railroad corporation.

Well, the Alabama and Chattanooga Railroad (owned by Boston investors), after paying $200,000 in bribes for a state charter, floated over $4. million in Alabama state bonds, secured by laying track mostly in Tennessee. Running out of funds, the Railroad went back to the Alabama legislature for an additional $2 million, which it subsequently used to build a hotel, and an opera house–in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Surprisingly, the endeavor soon went belly up, and the state acquired the assets in a auction sale–reversed by the courts–so the state had to expend another $1 million to formally seize the assets [4]. Eventually, an English firm acquired the assets and ran the railroad.

South Carolina had its own example. The 1870 Greenville and Columbia Railroad was a scam that involved a who’s who of then-current state politics–including ex-Governor Orr. The Railroad went bankrupt, the state had to take it over, and since the State guaranteed over $1.5 million of state bonds, it had to pay off the debt [5]. South Carolina also suffered through another railroad scandal, our old friend the defunct state-owned Blue Ridge Railroad became victim to its own bribery-created scam.

I might toss in for good measure and some perspective, that this was the period in which the Federal Government enjoyed its own railroad corruption scandal: the Credit Mobilier.

Despite spending all this money, southern operating railroad trackage declined by 20% during the 1870’s [6]. Whatever new rail lines were built were so fragile the Panic of 1873 killed them. The reader may be shocked that northern railroad investors picked up these lines at bargain prices in foreclosure [7].

Wrap Up and Segue Way: The Dog that Did Not Bark:

To the extent Reconstruction exhibited any coherence, it constituted an essentially political and civil rights transformation through constitutional amendments entirely focused on ending slavery and enfranchising southern Blacks. Having accomplished this (imperfectly and temporarily), the northern victors simply moved on and left the South (and Blacks) to their own devices. The result was as predictable as it was counterproductive.

What was missing from Reconstruction? The “dog that did not bark” was a functional equivalent to World War II’s Marshall Plan–a path into regional economic modernity. What the North wanted, and got, was revenge and ending slavery. What the South got was an imposed political, economic, and social revolution by external dictum–creating near chaos–and a counter political revolt–in its wake. Had the South been offered a guided path into the modern industrial world after Appomattox, along with a sustained political and civil rights revolution is a fascinating alternative history book yet to be written.

Northern Radical Republicans made no effort to impede the South’s return to its antebellum agricultural and cotton-dominated economic base. Reconstruction’s exclusive emphasis on civil, political, and electoral rights necessarily meant significant change in southern policy systems–but left economic development to the vagaries of whatever reactive Redeemer policy systems wrought.

Politically and militarily conquered, the South’s economy effectively leveled, the Reconstruction forced upon the South a cultural and societal transformation so rapid and transformative, if short-lasting, that for both understandable and ignoble reasons, resulted in a massive cultural and political blow back. The blow back not only wasted a decade, but led to the Region’s establishment of a regionally shared, if individually distinctive, set of state/local policy systems whose collective decisions regarding economic growth and economic development maintained the South’s “regional separateness”, and isolated it economically, politically, and culturally so that it could benefit little from the economic growth in other regions. Over the next hundred years, a region so isolated and chronically-depressed could survive only through an exodus of its desperate young and its repressed African-Americans.

The next module, the Divided Mind, dwells on how Reconstruction led to the formation of post-Reconstruction Redeemer policy systems. that in effect “doubled-down” on the the South’s 1800 decision to embrace an agricultural path in the modern era, and to organize its policy system and economic base to best achieve that end. That post-Reconstruction southern policy system fabricated a new alliance between planter and yeoman–again at the expense of Blacks–and doubled down on cotton and the agricultural economic base. To the extent the South industrialized, it did so through the efforts of a “New South” business class that drew its power and political leverage from its growing urban centers.

Footnotes

[1] Phillip Leigh, the Politics and Economics of Reconstruction (Westholme Publishing, 2017), pp. 2-3.

[2] Phillip Leigh, the Politics and Economics of Reconstruction, pp. 4-5.

[3] James C. Cobb, the Most Southern Place on Earth: the Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity (Oxford University Press, 1992), p. viii.

[4] William Rogers et al, Alabama: the A History of a Deep South State (University of Alabama Press, 1994) pp. 253-4).

[5] David Duncan Wallace, South Carolina: a Short History (University of South Carolina Press, 1951), pp. 578-9).

[6] Phillip Leigh, Southern Reconstruction, pp.74-5).

[7] Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (Harper and Row, 1988), pp. 535-6.